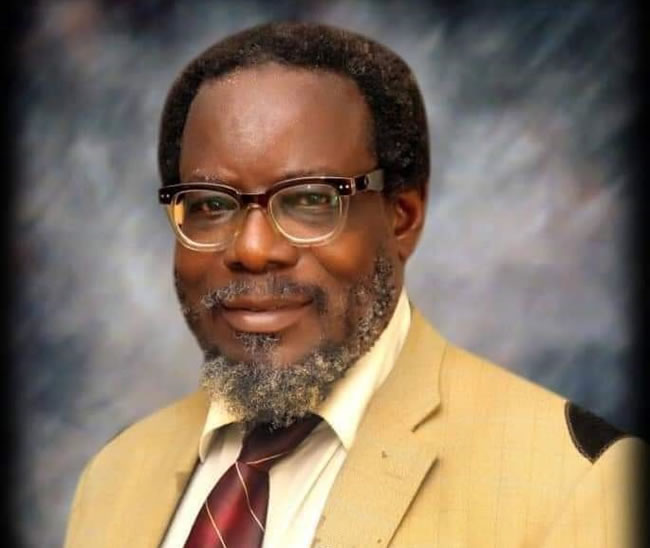

Comrade Gbadebo Adeniran, educationist and human rights activist, is the founder and chairman Centre for Anti-corruption and Open Leadership (CACOL). He told TUNDE ADELEKE his life story.

Sir, your name gives you away as a prince; can you throw some light on this?

I am Gbadebo Adeniran and I am supposed to be a prince, but somehow, our forefathers gave out our kingship to another family in our town; they gave it to a family that was not supposed to be in that lineage. They just felt like they wanted to give the impression that they were not bothered about kingship; that it didn’t mean much to them and that they could still be relevant without being king. So, that was it!

We were one of the foremost families that got to Iresi. Our house is called the head of Oke-Ile and we are five. We migrated from Oro in Kwara State to the present place. We got there early enough and somehow, along the line, those who founded the town didn’t think about kingship when they came.

How so?

They were only interested in the traditional setting where you talked about the family. We came about the same time the founders came.

Those earliest settlers constituted themselves into the ruling elite – ‘igbimo’. Then, at a stage, they converted the headship of that Igbimo to chiefdom; then about a hundred years or thereabout, they started kingship. Hitherto, they didn’t countenance it at all. Our forefathers had to rotate it among them and at a stage, they gave it out. When the struggle for it began, they reasoned that why did they need to fight over what did not confer special privilege on anyone? And what does anyone benefit from it. And you’ll begin to kill one another, rather than focus on things that could contribute to their livelihood. So, our family gave it out, not foreseeing that it would become the kind of royalty that it has become where you have so many benefits, luxury, and lots of things.

Can you let us into your parental background?

Well, my grandfather was a hunter and farmer and my grandmother was the head of the women, being married to a family that could be called a royal family. Then, she became a diviner, just like my grandfather too, Awoniyi, who was a ‘Babalawo’, a kind of diviner for the town. So, my father came and was born into that kind of environment, started as a farmer, and later established his farm. But as he grew up, he became a lumber jerk, producing planks. In those days, you combine many trades, and so, he later became a rock blaster which he went to Ibadan to learn and became the first to own a license for rock blasting. He’s supposed to own a quarry, but they didn’t have that kind of industry whereby they own a large quarry. So, they established a small quarry anywhere there was rock, and people wanted to blast. That’s what he was doing till around 1964/65 when he got injured on one of his legs. And I think he was infected with tetanus and thereafter went back into farming, cultivating crops – arable farming. He was Adeniran and was named Samuel after his conversion to Christianity. My mother was Victoria Oyeladun Ajike. In those days, all of them were industrious. She had to assist my father in farming but later became a merchant dealing in farm produce like kola nut, palm kernel, palm oil milling, and so on. At the right time, she would buy yam, new and dry, from different farms and sell; she would do food products, dry and fresh, and sell. She engaged in all sorts of things because everything we needed was produced by our parents.

How was your growing up?

I was born into an environment where farming was the main thing my parents were doing. I only have snippets of when my father engaged in lumber jerk (sawyer), I didn’t meet him in the trade; I met my parents on the farm.

On the day of my birth, my mother told me she was coming from the farm where she had gone to buy yams for sale. She fell into labour on the way, but she managed to get home. And as soon as she disembarked her loads, she went into the room and gave birth to me on a Friday.

When I grew up to about five or six years, we were on the farm; my immediate elder sister was about two and half years older than I was. She had started school and I also insisted I should go to school and they persuaded me to wait for another year. So, my sister was then virtually living with my grandmother. She was at home and I was on the farm. So, one fine afternoon, I just took off from the farm and headed for the town because I wanted to go to school. I went straight to my grandmother to tell her that my sister and I would have to go to school the following day. She asked if I had told my father and I said ‘no’. A lot of people met me on the way from the farm and asked me where I was going. But I successfully got home.

And schooling?

I actually started school around 1965, but I was bullied by one of the boys and I ran back to the farm. That was why I didn’t go again that year, but I started again in 1966. Of course, I didn’t stop again till I got to Primary VI; from Primary VI at Baptist Day School, Iresi to Baptist Secondary Modern School, Iresi, then to Grade II Teachers College where I had just a stint because I felt that there mode of operation was too strenuous for me. So, I didn’t complete it. Then, I went to a regular secondary school at Ogbomosho High School. But there was an issue between the school authority and the students. All of us that were coming from the same area were deemed to be the arrowhead of the protest and I had not been integrated well. That’s how they shut down the school.

So, I left and went to Okuku in Form II to join Odo-Otin Grammar School where I finished in 1981. Since when I was in Form III, I have been independent-minded, I have been taking care of what I was doing to supplement what I could get from my parents who were peasant farmers; I didn’t rely much on them. All the time I was on the farm, I supplemented what I got from my parents with what I could get from handwork – weaving baskets, making brooms, carving pestles, and things like that. We also moved around to gather dropped kola nuts because our parents allowed us to sell and keep the money to ourselves.

When I got to Okuku and things became a little tougher, I had to do menial jobs like bush clearing for people, to supplement what I got from home. That was how I managed to complete secondary school. But during that period, independent-minded I tried to be several things happened but I came out unscathed.

Where did you have your higher education?

I started a degree course before I went for NCE at Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo, and then back to the University of Lagos for a degree course. But I had about three years before I went to the College of Education; it was an experience I don’t want to relive. After Unilag with B. Sc. in Biology (Education), I did a lot of courses that helped me in the career that I chose. I did some Political Science, Public Administration, and some other courses, many of them by correspondence, some part-time. But along the line, there wasn’t any time I stopped working.

Throughout the time I was in higher school, I was a musician. I had dreadlock, and played reggae music; I was also a dramatist. Even when I left school, I still went into reggae music with Ras Kimono, who was my close ally. He was to sing behind me; when I did my demo, he said he was not ready to go into record-making then. I couldn’t secure a sponsor.

By that time, he had got sponsorship when he produced ‘What’s Gwan’. I previewed it for him. Some of our contemporaries were Dizzy K Falola, the late Majek Fashek, Oritz Wiliki, and the rest of them. It was then I met Olusegun Mayegun; he was still keeping his dreadlock then, and I advised him to go to school. Then, I met Daga Tolar who had also not yet attended a tertiary institution. I advised them that they couldn’t just stay on music alone. Mayegun was then the secretary of RUTRON. Because of the intellectualism that he exuded, even as a young school certificate holder, I insisted they should go to school.

Most people would dispute that you’re a Muslim…

But you have not asked me if I was a Muslim.

I got to know, but I never knew that you’re a Muslim.

You have to confirm with me.

Okay, are you a Muslim?

That’s a question you ought to ask! I don’t know who told you; who spread that rumor to you (laughs). You have to confirm that.

Yes, it was a rumor to the extent that I told you my father was Samuel and my mother Victoria. You know I was born into a Christian home. But then, the woman I wanted marry to happened to have come from a Muslim home. Not even the father who was Baba Adini of their town was feeling too strongly about it, but then, they had a group that didn’t want their daughter to be married to a Christian. Then, I reasoned that what does it cost me? So, I adopted Islam for marriage.

Before then, I was agnostic. I became agnostic when I was in secondary school. While in school, I experimented with all sorts of religions, including the Deeper Life and several others. So, when they brought Deeper Life to Okuku, we were the foundation members and I did it with all my heart. During long holidays, I experimented with other faiths which didn’t go well with me.

What did you find?

When I got to the tertiary institution, I was still one of the leaders of the Baptist Student Fellowship. At that time, I had made up my mind that religious grouping was just like social movements that give people succour when they are weary and friends they can relate with when they are in trouble, not because of divine intervention in what they do. Because my belief at that time was that God has created everything fine and that it’s the creatures that are remoulding things; that everything everyone needed was already there.

From the experiments in the study of Biology and others, I became agnostic; believing that you cannot understand God to the extent that you start to think you can be closer to Him than any other person; that God is universally merciful. If there is going to be sunshine, it will shine on everybody; rainfall, the same thing, or there will be a natural disaster, it doesn’t discriminate between religions. And many countries in the world do not discriminate between Christianity and Islam and they are doing well. Belief is about individuals.

So, why do we believe in Nigeria that what we believe will make us see the good face of the Highest?

So, at a stage when I was in reggae music, I became Rastaman. The way the Rasta believe is that you should not do a thing that will hurt your fellow men; even plant, you shouldn’t hurt. Rastas don’t eat meat, they are complete vegetarians. They don’t even uproot the vegetables; they pluck the leaves and ask the Highest for forgiveness for tampering with the structure of the plant.

Then, it got to a stage, I redefined conscience as a function of ones upbringing and exposure as dictated by the environment one finds himself. In places where cannibalism is the in-thing, it won’t make any difference to them to see fellow human being to be killed and made food. It’s just like the world of carnivores; they only kill the animals to eat. But among the cannibals, they kill other creatures of their type to eat. So, God has just allowed us that free will to do what we want to do.

Can you talk further about your career?

I have always been an educationist. After secondary school, I started work in a construction company where I was the site clerk, recording the number of materials used, the number of people who came to the site, and so on. After I left higher school, I started a private remedial centre in the Anthony area of Lagos. So, a colleague of mine who was a year younger invited me to help her with her school at Ojodu. Because of the rapid growth of that school, several proprietors and proprietresses started to call me to find out how she did it. That’s how I realised I could be an education consultant and I eventually became one. I have developed several schools and did so till I retired in 2020.

When did activism take over?

Talking about activism, I started when I was at Adeyemi College of Education as the National President of the Youth Environmental Programme for West Africa. Of course, I was part of the Press Club since when I was in secondary school. So, when we came in 1987, several things happened. We were associating with labour centres, particularly the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC). We believed we could do more than that. And the Civil Liberty Organisation (CLO) started with Olisa Agbakoba and others. We thought we could be integrated, but somehow, they restricted it more to lawyers and a couple of journalists. Somehow, we couldn’t function well at that level.

In 1989, Femi Aborisade was arrested and Lanre Arogundade came to say that we needed to do something about Aborisade. Beko Ransome-Kuti suggested that we put ourselves together and go to Broad Street in Lagos to sit to attract the attention of the media, that area being the core of the print media – Tribune, Daily Sketch, Daily Times, Tide, and others. Eventually, many members didn’t show up on time, so we retreated to Beko’s office to do a ‘Free Femi Aborisade’ protest.

What changed during his detention?

During the period of Aborisade’s detention, we discovered so many people were in prison that were not known. So, we decided to broaden our focus and change to the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights (CDHR). During that period, members of Labour Militant, who formed the core, asked us to remove Femi Aborisade’s name from the committee. So, we retreated and recruited others; we brought the Ife Collectives: Toye Olorode, Dipo Fashina, and others.

There was no phone at that time; every letter had to be delivered by hand. In 1990, we tried to organise the national conference, but Babangida stopped it, and we moved on. Later, by 1991, we realised we couldn’t be running splinter organisations because we wouldn’t be strong enough. We invited other organizations and we became Campaign for Democracy (CD).

CD was able to achieve many things. It got to a stage where Beko, Baba Omojola, Segun Mayegun, Femi Falana, and Fela Anikulapo were detained in Kuje Prison. Before they came back, a lot of things went wrong.

By 2007, we started Campaign against Corrupt Leaders (CACOL) and rebranded in 2017 to Centre for Anti-Corruption and Open Leadership. I retired in 2020.

How would you describe yourself as a family man?

As you have just mentioned, as a family man, I love my family and I do everything possible to ensure that none of my family members asks for anything that he or she does not get. I just know that I care for my family and safeguard their interest.

What do you detest in people?

I prefer stealing to lying. I don’t like it when people pretend to be what they are not. So, most of the time, if you steal and you confess; you can be forgiven. But if you steal and lie, it will be difficult to discover what you are.

When was your greatest moment?

I don’t think I have the greatest moment. It was when I represented CDHR when Nelson Mandela visited Nigeria in 1990. Before then, I was secretary of the National Union of Food, Beverage, and Tobacco Employees in Ibadan and I also had the opportunity to address the gathering on May Day in Ibadan.

What about your saddest day?

I don’t think I have. But I should tell you that when I was secretary of CDHR, I was also secretary of the Gani Fawehinmi Solidarity Association when Babangida was to be installed as Jagunmolu of Oyo State, we went to court that he didn’t deserve it. But before the case was decided, the state was split into Oyo and Osun. I don’t think I have what I can describe as the saddest day.

How do you relax?

I dance and sometimes, I play music; then, I drink when I have to and of course, I read. I don’t think there is anything more than those things I mentioned. But I go to my town to fraternise with the people, the old folks there.

ALSO READ FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE