The cap does not immediately affect Nigeria and Libya as the two OPEC states were exempted from the limits to help their oil industries recover. The deal, however, was that as soon as Joint Monitoring Committee (JMC) in the OPEC can determine that Nigeria has stabilised enough, it will have to cap its oils too. However, there is no timeline on when this will take effect.

There have been reactions to the news, as stakeholders in the oil and gas industry have said that the decision to cap Nigeria’s oil production was “a bad omen for the oil industry and Nigeria’s economy, especially when the budget proposal is based on 2.2 million barrel per day and at $44.5 per barrel,” according to Felix Amieyeofori, Managing Director of Energia Limited, in a media report.

Business Day reported Amieyeofori as saying that “Restricting production at 1.8 million may pose serious challenge for the entire country. For producer, what this would mean is that there will not be incentives to add fresh production. That will affect work programme activities.”

But Biodun Adesanya, President, Nigerian Association of Petroleum Explorationist (NAPE) saw the development differently. According to the newspaper, Adesanya said Nigeria can currently produce between 2.5 and 2.6 million barrels per day, but it is difficult evacuating this to the terminal because of militant attacks. Thus, capping oil production was not the real problem.

In separate interviews with this reporter, two experts are of the views that the potential oil cap may not have a “significant” impact on government’s projected revenues and that it could potentially boost the country’s oil revenues on the long run.

Mr Waziri Adio, Executive Secretary, Nigeria Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (NEITI), estimated that potential cap in oil production will “definitely impact our projected oil revenues, bearing in mind that the budget was based on a production benchmark of 2.2 million barrels per day. This means production figure will be lower by 400,000 barrels per day.”

“However, he said “the real impact might be mitigated by three factors; one, the fact that we have not been achieving 2.2mbp target for some time now due to vandalism, militancy and shut-ins. Two, the lower production figure might be compensated for if oil price stays above the $44.5 per barrel benchmark price, meaning there might not be a major reduction in oil revenues. Bearing in mind that we are likely to see higher oil prices with capped OPEC production, which will reduce supply and likely increase oil price. “Three, oil revenue as a percentage of total government revenues is reducing, with increases in non-oil revenues and other revenue sources. In sum, the impact on government revenues might not be very significant, and might be compensated for by other factors, as explained earlier.”

Dr Austin Nweze, Principal Consultant, Bellwether Consulting and lecturer at Pan Atlantic University, Lagos, views the potential cap as a blessing for the country. “What OPEC as a body has been trying to do is to shore up the price of oil. Nigeria will benefit with high oil price. You know the concept of demand and supply comes in here in that once OPEC creates artificial scarcity by reducing glut in supply, it will force prices upward.”

Whereas there may be not be a significant impact of potential oil cap on government revenues, the anxiety among observers and analysts is that shrinking oil revenues signals potential crisis for the economy, as the government relies almost exclusively on its oil as major source of revenue.

Nigeria’s oil sector provides for 95 per cent of the country’s foreign exchange earnings and 80 per cent of its budgetary revenues, records show, and this makes a few analysts jumpy, considering the fact oil revenues are shrinking, as evidenced by data collated by BudgIT.

Nigeria’s challenge with budget funding

It will be recalled that Nigeria has, in the last two years, struggled to fund its budgets. In 2016, country’s President Muhammadu Buhari sought National Assembly’s approval for an external borrowing plan of $29.96 billion to cover budgetary deficits for 2016 to 2018. This challenge led to the government to put two of its aircraft for sale, three months to the end of the year. Currently, the N7.44 trillion 2017 budget has a deficit of N2.21 trillion, which suggests that 29 per cent of the budget may likely be funded through loans, foreign and domestic, especially as Nigeria’s Finance Minister, Kemi Adeosun had, until recently, campaigned for taking loans to finance the budget.

But it is important to note that Nigeria’s decided lack of saving culture contributed to Nigeria’s inability to fund its budget. It will be recalled that NEITI indicted Nigeria on its saving culture, saying that country’s oil revenue savings is among the lowest globally. “Nigeria has about three decades of experience in implementing different oil revenue funds. However, attempts at oil revenue savings have been plagued by contested legal frameworks, governance issues and inadequate political will.

“Nigeria has one of lowest natural resource revenue savings in the world. The balance in the three funds (0.5 per cent stabilisation fund, ECA and NSIA) is less than $3.9 billion, not enough to fund 20 per cent of 2017’s federal budget,” Waziri Adio, NEITI’s Executive Secretary said in interviews with media, recently.

Decline in oil revenues is characterised by several factors; domestic and foreign, experts say. Attacks on oil pipelines, bunkering, and fall in global oil prices are most critical factors mitigating rise in oil prices, analysts believe. These have led, they said, to lower than projected oil productions and exports. Nigeria projected that it will produce 2.2mbpd, with which it planned to drive the economy. But records show that Nigeria has not been able to achieve this.

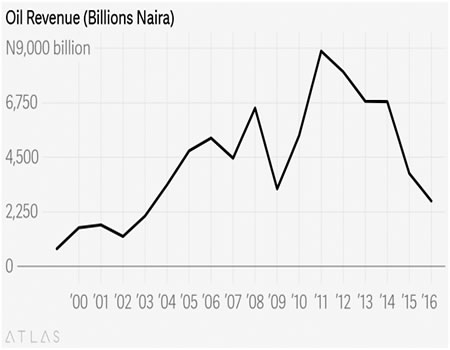

Nigeria’s oil revenue fluctuated between N1,591.68 billion and N5,396.09bn from 1999 and 2010.. However, oil revenue jumped from N5,396.09 billion in 2010 to N8,878.79 billion in 2011, dropping to N6,793.82 billion in 2014. However, oil revenue significantly dipped to N3,830.10 billion in 2015, where it dipped further to N2,693.91 billion in 2016.

Contributory factors to decline in oil revenues

Currently, India, Spain and Netherlands buy 43 per cent of Nigeria’s crude oil, according to Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), but country’s biggest oil buyers are aggressively pushing the low emission and green energy policy and are adopting Electric Vehicles (EV) as acceptable mode of transportation. There are indications that global production of EVs will increase by 35 per cent in 2030, according to IEA estimates.

With the rising electric car demand across the globe posing a threat to big oil companies and by extension, oil producing countries, the chances of increasing oil revenues may likely become significantly lower in a few years, analysts believe. OPEC has already raised its 2040 EV fleet prediction to 266 million from the 46 million it anticipated in 2016.

A study by Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) projects that electric cars will reduce oil demand by eight million barrels by 2040, thus, “growing popularity of EVs increases the risk that oil demand will stagnate in the decades ahead, raising questions about the more than $700 billion a year that’s flowing into fossil-fuel industries,” as stated by a Bloomberg report.

There is also the issue of India’s boycott of Nigeria to buy oil from the USA. It will be recalled that India concluded plans to start buying oil from the United States of America as it looks to diversify its sources of the commodity. Earlier in July 2017, Indian Oil Corporation, the country’s largest refiner, sealed a deal to import 1.6 million barrels of the US crude for delivery in the first week of October to its Paradip refinery on the east coast, its first ever purchase of the US crude.

Impact of continued decline in oil revenues

“Since government is the biggest spender in the national economy, and with low revenue coming in, it means government may not have enough to spend on other critical infrastructure,” Dr Nwaeze said, suggesting that the country may likely not experience any significant impact of Buhari’s economic growth and recovery plans.

According to Dr Nwaeze, it is unlikely that Nigeria would be able to achieve its 2017 budgets goals, due to decline in oil revenues. “The indicators show that it is a pipe dream. There is no way budget targets can be met without policy changes both in fiscal and monetary terms. The fundamentals must change to a new normal. The revenue target is not likely to be met. Serious critical and strategic thinking is required, which is currently absent. Since government is the biggest spender in the national economy, and with low revenue coming in, it means government may not have enough to spend on other critical infrastructure,” he said.

The issue is, if Nigeria cannot meet its economic recovery targets, this signals a lot of problems for the economy, as it relates to poverty reduction and closing the inequality gap. Without investments in infrastructure, these problems will continue to persist, sociologists say. Without social and economic infrastructure, challenges of vast inequities in terms of access and quality of services in the health, education, and water, will continue to pose significant crisis in the country, experts have warned. The outcome of these, experts believe is increase in poverty levels in the country.

A 2016 report from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) puts the number of Nigerians living below poverty levels at about 112 million (representing 67.1 per cent) out of total population of 167 million people. In 2010, the World Bank reported that 68 per cent of the population lived below the international poverty line of US$ 1.25 a day and as studies have shown, women, children and elderly are major vulnerable groups when dealing with poverty.

Poverty affects millions of Nigerian children, leading many of them into poverty induced child labour. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), there are an estimated 15 million children under the age of 14 involved in child labour in Nigeria. “The high level of diverse and tedious jobs that children execute in dangerous circumstances is particularly worrying. These jobs include being street vendors, beggars, car washers or watchers and shoe shiners. Others work as apprentice mechanics, hairdressers and bus conductors while a large number work as domestic servants and farm hands,” UNICEF said in a report.

According to UNICEF, working children experience “fatigue, irregular attendance at school, lack of comprehension and motivation, improper socialisation, exposure to risk of sexual abuse, high likelihood of being involved in crime.”

Lack of social infrastructure is also an issue. Water scarcity and inadequate sanitation has led to 73,000 deaths in 2015 in Nigeria, according to a UK-based organisation, WaterAid and the country’s Federal Ministry of Health. WaterAid Nigeria’s statistics show that “63 million Nigerians have no choice but to get water from wherever they can,” and 57 million people lack access to safe water. Also, over 130 million people don’t have access to adequate sanitation in Nigeria, two thirds of the population, according to the organisation.

Other development challenges such as unemployment, inclusive growth, inequality (in terms of income and opportunities); power challenges, a poor regulatory environment, and a lack of access to finance (to drive the private sector which remains the major driver of the economy), will continue to have adverse effect on poverty reduction drive by the government, should the country fail to fund its budget.

Way forward

Decline in Nigeria’s oil revenues creates an opportunity to look into other extractive areas in Nigeria for revenue. But first, according to Mr Adio, “we need to optimise the opportunities in the oil and gas sector. We need to focus on the entire value chain. We can make more money, as well as save a lot of money, by refining our crude oil, by investing more in petro-chemical sub-sector, and by utilising gas flared. Also, this is a major opportunity to focus on the solid mineral sector, ensure we put in place and enforce the regulations and policies that will attract domestic and international investors to the sector and ensure that we add value to what we extract.”

Dr Nwaeze said decline in oil revenues “could be an opportunity for government to invest or encourage investment in other sectors of the economy. Because of the unhealthy focus on oil and gas, other sectors are neglected. This is easy money making for the ‘boys.”

There is a need to look into other extractive sector, such as solid minerals as an avenue for revenue generation. It will be recalled that Dr Kayode Fayemi-led Ministry of Mines and Steel Development developed a roadmap for the development of the solid minerals sector in Nigeria. Some say the ministry is already implementing the roadmap. With a N30 billion fund put in place for the development of the sector, the ministry has started to “actively” market the sector to local and international markets.

“Nigeria is actually more endowed in solid minerals. We have 44 different solid minerals in commercial quantities, spread all over the country. This sector provides enormous opportunities for job and wealth creation, for economic growth, and for revenues to government. But a lot needs to happen for us to maximise the opportunities in the sector. We need to ensure that government provides business-friendly regulatory framework and investible geo-physical data, provides needed oversight and reduces, if not eliminate, illegal operations, and puts in place incentives and sanctions for value-addition,” Adio said.

Dr Nwaeze submitted that “Oil contributes about 17 per cent or so to the GDP. The sector employs less than 20, 000 people. It generates about 90 per cent of government receipt or revenue. This is not healthy at all, generally speaking. This is one reason we have been clamouring for other sources of revenue generation other than oil. The economy should be more diversified and decentralised for it to create the kind of national wealth that will trickle down to the citizens by way of improving the standard of living of the people, thereby positively impacting on the quality of life of the people. The contribution of oil to the GDP should not be more than five per cent, generating not more 20 per cent of government revenue.

“The future of Nigeria’s economy and economic development is not in oil and gas but in science, engineering and technology. Therefore, government investments and focus should be directed at these areas. This will catalyse other sectors of the economy. Nigeria has to become original equipment manufacturers. Be reminded that national economies are created, not inherited. The managers of Nigeria’s economy have this inheritance mentality which works against any progress. Technology holds the key to national economic development via industrialisation.”

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries