In a dramatic expansion of US immigration enforcement, the Trump administration is trying to deport a group of migrants—including individuals from Mexico, Cuba, Vietnam, and Laos—to South Sudan, a country on the verge of civil war.

The move is part of a broader strategy to send deportees, even those not from South Sudan, to third countries considered dangerous or unstable, raising alarm among legal experts and human rights advocates.

These men are currently believed to be held at a US military base in Djibouti, following a federal judge’s order temporarily blocking their transfer to the South Sudanese government.

While US immigration law allows for the deportation of certain individuals to third countries in rare circumstances, the Trump administration is pushing the boundaries of that policy—planning deportations to dangerous regions like South Sudan, Libya, and even a maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

Legal experts say this strategy deviates sharply from past practice.

“The trifecta of being sent to a third country, plus the intended scale, plus the punishment-is-the-point approach — those three things in combination, that feels very new,” said Sarah R. Sherman-Stokes, a professor at Boston University School of Law.

According to immigration scholars, the broader goal may be deterrence.

As Muneer Ahmad, a professor at Yale Law School, explains, deporting people to conflict zones is a “concerted strategy” intended “to both disincentivize people from coming to the United States and to incentivize self-deportation.”

Who Are the Deportees?

A New York Times review of court records revealed that all eight individuals had been convicted of violent crimes. US officials described the detainees as “barbaric monsters” and released a 70-page summary of their criminal histories.

Critics argue this move is part of a public campaign to undermine the judiciary, which has slowed the administration’s deportation efforts.

The approach contrasts starkly with the case of over 100 Venezuelans deported to El Salvador—many of whom had no criminal records and were targeted based on superficial traits like tattoos or clothing.

One deportee, Thongxay Nilakout, a Laotian national, fatally shot a German tourist in 1994 at the age of 17. The victim’s daughter, Birte Pfleger, expressed conflicted emotions upon learning Nilakout might be sent to South Sudan.

“The eight men are all ‘criminals convicted of heinous crimes,’” she said. “But,” she added, “that did not excuse what she saw as the government ‘violating’ their right to due process.”

She warned, “If we consent to ignore the fundamental rights of some people, then who is to say these rights will apply to us and who decides when and for whom rights apply?”

Why South Sudan?

President Trump confirmed on May 22 that the men detained in Djibouti were en route to South Sudan—a country on the brink of civil war, where recent fighting has displaced tens of thousands.

The saga began in April when South Sudan initially refused to accept a man the US tried to deport.

The next day, Secretary of State Marco Rubio retaliated by suspending visas for South Sudanese citizens, accusing the nation of failing to repatriate its own nationals—despite later evidence that the man in question was Congolese.

South Sudan eventually allowed the man in, citing “the spirit of the existing friendly relations,” but the visa ban remained in place.

The country, which depends heavily on US financial and humanitarian aid, is now seeking to have the ban lifted.

A spokesperson for South Sudan’s government did not respond to requests for comment.

What Other Countries Are Involved?

El Salvador: In March, the US deported nearly 140 Venezuelan men—allegedly gang members—to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador under the rarely used 1798 Alien Enemies Act. Families of the deported men have filed lawsuits, alleging wrongful imprisonment and lack of due process.

Rwanda: Rwanda’s foreign minister recently confirmed preliminary talks with the Trump administration to accept deportees. Although Rwanda has previously worked with Western nations on asylum matters, critics argue the country’s poor human rights record and history of refugee mistreatment make it unsafe.

Libya: Plans to send migrants from Southeast Asia to Libya were blocked by court intervention. Libyan authorities later denied any agreement to accept deportees. The country remains in civil war, and migrant detention centers there are widely condemned as “horrific” and “deplorable.”

Mexico: On May 24, a federal judge ordered the US government to facilitate the return of a Guatemalan man wrongfully deported to Mexico. Judge Brian E. Murphy criticized the deportation process for its “errors” and lack of due process, stating the man was likely to “succeed in showing that his removal lacked any semblance of due process.”

What Are the Legal Issues?

The administration’s tactics have provoked a wave of legal challenges.

In April, Judge Murphy mandated that deportees be given at least 15 days’ notice before being sent to a third country, and be granted a hearing to raise fears of persecution or torture.

Despite this, Homeland Security deported the eight men, allegedly informing them that they were headed to South Sudan. In a May 21 hearing, an incensed Judge Murphy said, “The department’s actions in this case are unquestionably violative of this court’s order,” warning that officials involved might face criminal penalties.

US law forbids deportation to countries where individuals may face threats to life or freedom due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion—or where they are “more likely than not” to be tortured.

What Is Trump’s Goal?

President Trump has long vowed to escalate deportations. Since taking office, his administration has aggressively rolled back protections for many immigrants and expanded the pool of individuals eligible for removal. This includes moves to expedite deportations and limit judicial oversight.

Federal judges—Murphy, James E. Boasberg, and Paula Xinis among them—have indicated they may hold federal officials in contempt over these actions.

Experts say deporting individuals to visibly dangerous countries may be part of a strategy to instill fear and reduce migration. It may also serve a broader political goal: eroding the judiciary’s ability to limit presidential power.

Andrew O’Donohue of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace calls this tactic “court baiting”—deliberately provoking legal battles over politically sensitive issues to pressure courts and shift the balance of power.

So far, the federal judiciary has resisted. But as deportations continue, the constitutional stakes remain high.

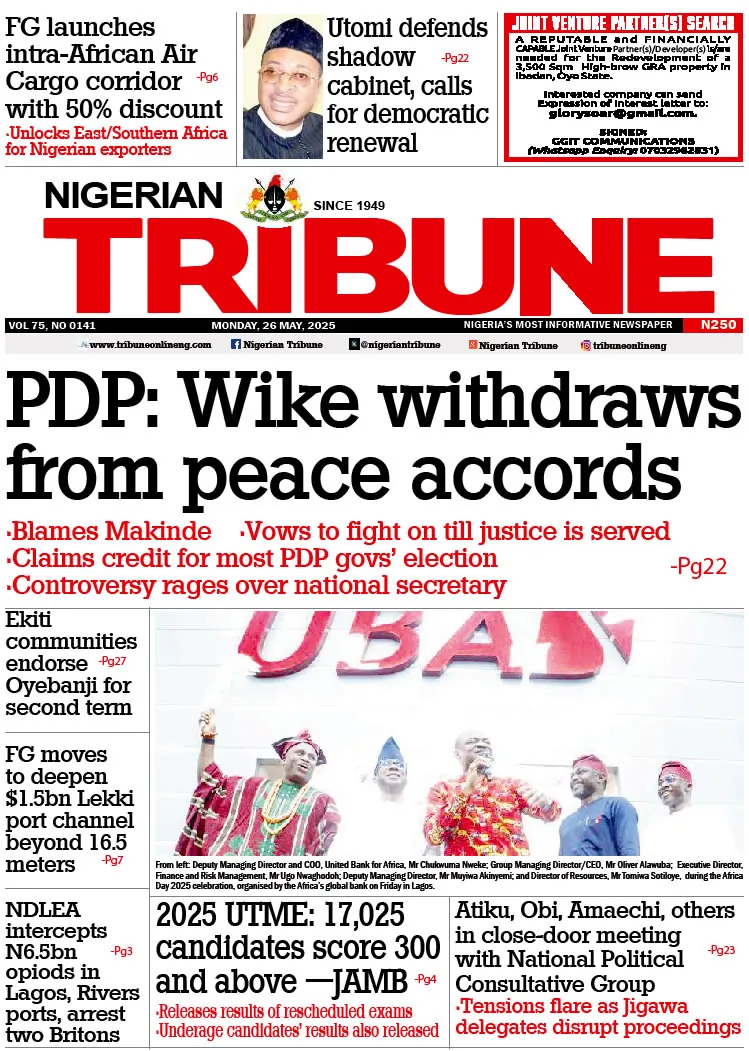

ALSO READ TOP STORIES FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE