It was the literary icon Chinua Achebe, who in his 1958 book, Things Fall Apart, shared one of the most profound Afro-centric didactic quotes: “Until the lion learns to write, every story will glorify the hunter.” As cliché as it might sound to some, this quote underscores the importance of knowledge production in Africa. If money lubricates the wheels of missionary and evangelistic endeavours, it can be said that knowledge production lubricates the wheels of societal consciousness and advancement.

Knowledge production—both as a concept and as an endeavour—takes centre stage in the development and evolution of human societies. Through knowledge production, we humans are able to make sense of our world, avail ourselves of access to a wide range of ideas and insights, critique existing concepts, postulate about developing theories, and push the boundaries of knowledge to birth innovation. Knowledge production opens up a portal to the thorough examination of histories, cultures, and narratives to shape our understanding of the world.

At its core, knowledge production is an endeavour that aggregates the creation, dissemination, and utilisation of information that contributes to the intellectual advancement of societies. It transcends the mere acquisition of facts and extends into the interpretation, synthesis, and critical engagement of collated information about the past and present. It is the process through which societies engage with their past, interpret the present, and lay the foundation for future explorations.

If knowledge production is so defined, it then begins to make sense why knowledge production about Africa is such a necessary endeavour. The importance of Afro-centric knowledge production ties back to a foundational need to eliminate preconceived notions and stereotypes that emasculate the African continent and present a nuanced, comprehensive narrative that transcends the constraints of ignorance and bias.

As a continent that has been both a witness to ancient civilizations and a crucible of colonial hegemony, African history has passed through the metaphorical fire, emerging as a rich bundle of insights ready to be unravelled, critiqued, analysed, and understood to contribute to a more inclusive and interconnected global history.

The Challenges and Opportunities in Knowledge Production about Africa

Knowledge production about Africa is not without its multi-dimensional challenges. Linguistic, cultural, and archival barriers have been the biggest obstacles facing scholars in their quest to unearth Africa’s layers of history and foster a heightened level of knowledge production and output. The diversity of languages spoken across the African continent—which is naturally a blessing—has, in this case, been an obstacle, making it difficult and more nuanced beyond conventional Western methodologies and approaches to effectively collect and aggregate information useful for knowledge production, especially since Africa relatively recently came into written history.

It is also noteworthy to consider how the colonial influence on the African formal education system and library and archival systems largely dictated what was preserved and the lens through which historical documents are largely interpreted. This makes it doubly challenging to uncover narratives about Africa and interrogate archival endeavours that have often marginalised indigenous voices and perspectives.

As challenging as knowledge production about Africa is proving to be, there are several opportunities for transforming the narratives, some of which are currently being leveraged by the prevailing Afrocentric scholars and their knowledge production. The increasing recognition of the importance of indigenous languages—now made more potent by technological advancements in archival efforts—has made it possible to embark on an inclusive and comprehensive scholarship of African history and knowledge production about this history.

As internal demands for knowledge production about Africa continue to increase, it is vital to recognise how such forms of knowledge production could be beneficial to the African continent. This concept of knowledge production about Africa is another avenue to reinforce the need for town-gown collaboration, as it transcends academic scholarship. There is a need for policymakers, activists, political leaders, indigenous leaders, and African communities to unite and actively participate in this continued process of knowledge production as a means of addressing misconceptions and stereotypes about Africa, fostering a deep understanding of Africa’s long-standing and richly diverse history, and championing and promoting African voices in strategic participation in global discourses.

Also Read: Senator Natasha congratulates DSP Jibril on honourary doctorate award

Language, Archives, and Knowledge Production about Africa

Knowledge production as an endeavour cannot be fully defined without reference to both languages and archives. These two concepts—which could be called the protagonists in the tale of knowledge production—play unique and interdependent roles in shaping the narratives we encounter, modifying our perceptions of the concept, influencing the questions we ask, and determining whose voices are heard in the echoing corridors of historical discourse.

The evolution of knowledge production in Africa ties back to broader historical developments on the continent. Historically, the study of Africa reflected largely Eurocentric perspectives, which were not largely a case of the hunter being the sole storyteller, dictating the provisions for the story. The earliest documented knowledge production from Africa marginalised indigenous voices and reflected stereotypical conclusions.

However, the latter half of the 20th century brought about a systemic shift as scholars, activists, and intellectuals—particularly those of African descent—began challenging prevailing narratives and advocating for a more inclusive, authentic representation of Africa’s history. This marked the emergence of African historiography, a movement that charged itself with the reclamation of agency in shaping the narrative of the African continent.

The Roles of Languages in Knowledge Production about Africa

Beyond being a means of communication in a social community, language also serves as the conduit of culture and identity, forming the basis through which people express their cultural leanings and identities. On the linguistically diverse African continent, languages are the key markers of cultural groups and historical evolution. Each African language captures and projects a unique worldview, offering insights into the traditions, beliefs, and values of its speakers. This is why there is an inherent difficulty in effectively translating the word “omoluabi,” a unique Yoruba concept.

Languages also serve as the protective sac covering the delicate face of indigenous knowledge. Through these languages, ancient wisdom and indigenous knowledge systems have been preserved and passed down across generations, making them more memorable and easier to remember through vehicles such as poetry, songs, folklore, and chants.

Through languages, we have made inroads to and continue to research insights into agriculture, medicine, governance, and spiritual practices in African history. Knowledge production about Africa necessitates a deliberate effort to engage with and preserve these indigenous languages, as they hold the keys to unlocking centuries-old knowledge that can enrich our understanding of sustainable practices, traditional governance structures, and holistic approaches to well-being.

The role of languages in knowledge production about Africa will not be complete without referencing the decolonization of narratives around African history and the reclamation of African perspectives. Language plays a pivotal role in the decolonization of African history, serving as a tool for reclaiming agency, challenging Eurocentric interpretations, and fostering a more authentic representation of Africa’s past. Knowledge production about Africa, therefore, necessitates a conscious effort to reclaim African perspectives embedded in indigenous languages.

However, the reliance on oral traditions is not without its linguistic challenges. Many indigenous languages are marginalised or endangered, facing the risk of extinction. This, therefore, brings us all a dual responsibility: to document and preserve endangered languages, ensuring their survival, and to develop linguistic strategies that bridge the gap between oral traditions and academic discourse. This requires collaboration with linguistic experts, community members, and language preservation initiatives to overcome the linguistic barriers that may impede the exploration of Africa’s rich oral histories, and our decision to organise this panel discussion on the next edition of the Toyin Falola Interviews is a step in the right direction.

The Roles of Archives in Safeguarding Historical Documents for Continued Knowledge Production about Africa

All forms of archives—ancient manuscripts, colonial records, contemporary documents—serve as custodians of historical materials, and in the African context with a dredged colonial past, archives house materials that bear witness to the rich, multi-layered, and interwoven histories of African communities, rife with cultural interplays, phases of civilizations, and power dynamics.

Archival efforts in Africa are both a testament to triumphs in preservation and proof of challenging obstacles. Although our archives help us uncover newer narratives about historical Africa, they also leave us reflective on how colonialism ran its course on the African continent and the indelible tracks it has left across the face of our land, scattering pockets of African history across several countries—relics taken away from the continent. These two sides of the coin are proof of one thing: the need for collective and comprehensive archiving efforts in Africa.

It is only through comprehensive archiving efforts that knowledge production about Africa can be scaled to position Africa as a global shaper, owning its own place in the global discourse. Although the fragmentation of our archives—not without linguistic and geographical barriers—pposes a great threat to scholarly research in African history, a unified and collective approach to archiving, one that involves governments, institutions, scholars, and communities, will help to digitise and make our historical documents more accessible. This is a clarion call to commit to justice, transparency, and the recognition of Africa’s agency in shaping its narrative.

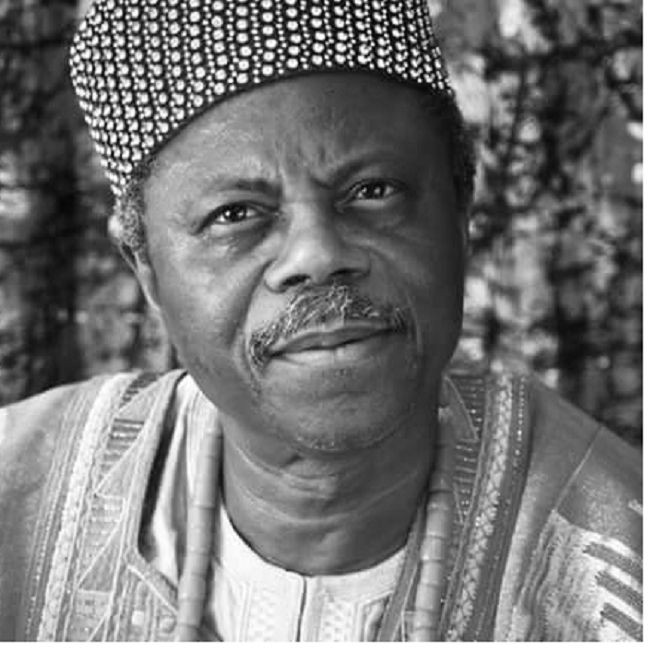

There is a role for everyone, and the interplay of these roles—especially how they can all come together as concerted efforts to champion knowledge production about Africa—will be comprehensively discussed at the next edition of the Toyin Falola Interviews, scheduled to be held on March 3, 2024. Join Professors Abiodun Salawu, Fallou Ngom, Ghirmai Negash, and John Mugane in the discourse.

Sunday, March 3, 2024

5 PM, Nigeria

10 AM Austin

Register and watch:

https://www.tfinterviews.com/post/Languages

Join via Zoom.

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81714206181

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Relationship Hangout: Public vs Private Proposals – Which Truly Wins in Love?

- “No” Is a Complete Sentence: Why You Should Stop Feeling Guilty

- Relationship Hangout: Friendship Talk 2025 – How to Be a Good Friend & Big Questions on Friendship

- Police Overpower Armed Robbers in Ibadan After Fierce Struggle