Attacks by armed groups in the creeks of the Niger Delta have always been seen as the major cause of crude oil production disruption in the region, resulting in the loss of very scarce resources and, in some cases, lives. But that’s not all there is. What is rarely known is that beyond armed struggles — which have been largely controlled in the region recently — patches of disparate disruptions still happen and they are insufficiently reported.

Some last as short as a day but happen repeatedly while others last as long as 29 days and still repeat. When the figures are summed over a longer period — a month and more — surprising numbers show up and huge losses are revealed; which, disturbingly, robed Nigeria of the very sought-after resources it needs to liven up its economy.

Costly price

Nigeria relies heavily on crude oil sales for its revenue and anything that disrupts production intricately disrupts the oiling of its wheels. Over the years, the disruptions in the region have grown from protests by disgruntled locals in host communities to protests by unsatisfied staff of oil companies, power outages and unplanned shutdowns of facilities, leaks due largely to weak infrastructure and seldom scheduled maintenance. Other issues like flare maintenance, equipment failure and fire outbreak have also contributed.

To make sense of the rate of production disruption in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector, Nigerian Tribune gleaned one-year data of production disruption in the sector contained in the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation’s (NNPC) monthly FAAC reports from March 2020 to February 2021. The reports covered from January to December 2020. Also, data of the average crude oil and condensate production contained in NNPC’s monthly financial and operations reports from January to August 2020 was gleaned.

The reports show that Nigeria lost 36.3 million (36,262,664) barrels of crude to the disruptions in the region in 12 months.

In January 2020, the disruption cost Nigeria 2.7 million (2,644,900) barrels of crude oil. The major disruption came from the shutdown due to leaks at Bonny terminal. Only the Bonny shutdown which lasted 15 days led to the cumulative loss of 1.9 million (1,950,000) barrels. On the other hand, the corporation’s monthly performance data for January shows that in the same month, Nigeria had an average daily production output of 2.07 million (2,072,916) barrels. This means that the country lost 1.3 days (about 31 hours) of production in January due to the disruptions.

In the next month, an analysis of the report reveals that 1.9 million (1,972,653) barrels were lost. In the same month, NNPC performance data shows that 2.07 million (2,069,678) barrels was the average daily output of the country. In this complex, 1.05 days — an average of 24 hours — of production was lost.

In April, the rate of losses climbed to a new high of up to 3.9 million (3,928,003) million barrels for the year. The most interesting of the shutdowns is that of Egina terminal which cumulatively lasted for eight days due to power outage. The average daily production rate — 2.04 million (2,036,206) barrels — did not change significantly in relation to the previous month’s.

The average daily production output tanked in May — 1.75 million (1,749,798) barrels — while the loss went the opposite direction at 4.3 million (4,324,147) barrels. It continued in June: 1.69 million (1,687,403) barrels daily output and 3.8 million (3,828,894) barrels loss. The downward trend in daily output continued in July — 1.65 million (1,653,426) barrels — while the loss got better at 3.0 million (3,049,216) barrels, though still very high. The trend didn’t abate in August. The output went further down to 1.65 million barrels (1,649,896) while the loss more than halved at 1.4 million (1,431,645) barrels, in relation to the previous month’s.

The loss trajectory changed the following month — 1.8 million barrels (1,857,665) — and halted a little in October at 1.8 million (1,822,778) barrels. Then it resumed in the following month — 2.0 million (2,016,753) — and hit an all-year high in December at 6.4 million (6,462,510) barrels.

Huge impacts — missed opportunities at development

The loss holds a very significant place in Nigeria’s economy. In fact, in financial terms, the loss means that Nigeria threw away the chance of injecting about $1.8 billion ($1,813,133,200) into its ailing economy — if the loss is multiplied at the average crude cost of $50 per barrel.

This is in the midst of budget deficits — the new borrowing of N4.28 trillion to finance the 2021 budget will push public debt to about N35 trillion over a four-year period.

The country is strewn with poor infrastructure: poor roads, a weak healthcare system, a not-properly-developed railway system and a poorly-funded education system. All these need a huge investment to improve on.

For instance, the healthcare system which is one of the most critical sectors of any nation is in dire need of funds. According to the Abuja Declaration, Nigeria and other African countries should allocate not less than 15 per cent of their annual budgets to healthcare. But due to inadequate funds and lack of political will, the sector’s budget funding has hovered below the agreed percentage since the declaration was made in 2001.

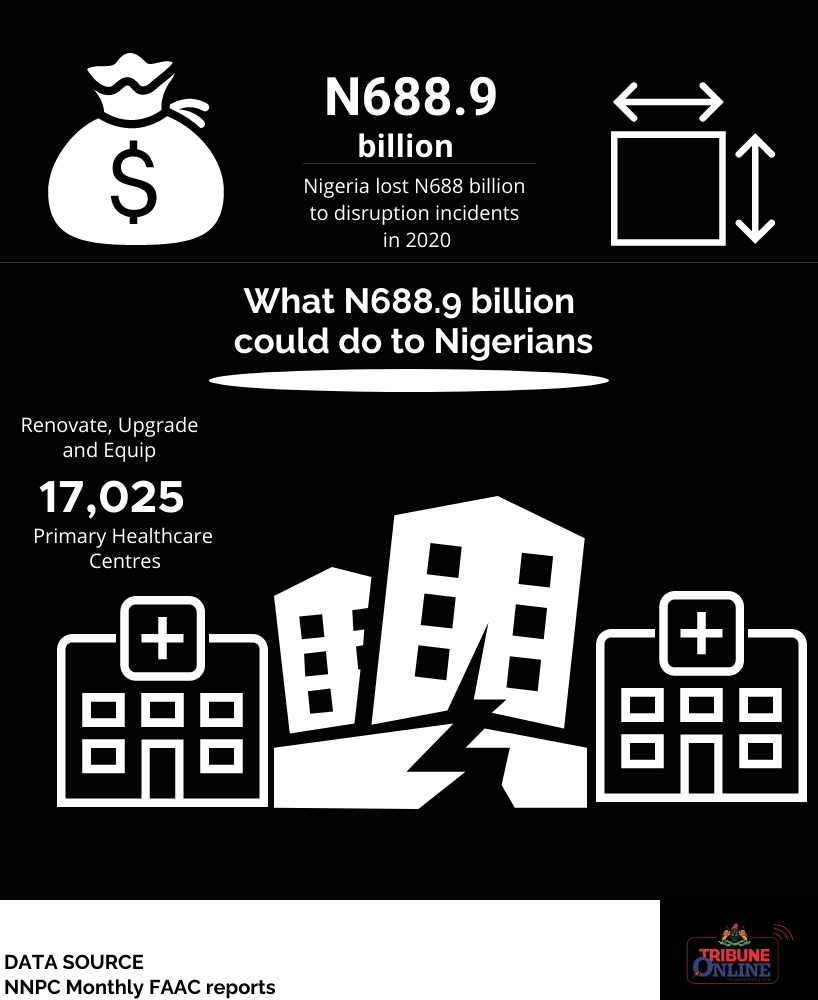

To make sense of the tangible implications of this loss, Nigerian Tribune analysed what the $1.8 billion (1,813,133,200) — N688.9 billion (688,990,616,000) at CBN rate — could have done in the country.

The analysis used a project — Renovation, Upgrade and Equipping Of Umuobiala PHC in Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State — contained in the federal government’s 2021 budget details as a base project to estimate how many primary healthcare centres the lost amount could have renovated. The base project was awarded at a cost of N40.4 million (N40,470,000). At this amount, it means the lost amount could renovate, upgrade and equip 17,025 primary healthcare centres in Nigeria with each of the 36 states and Abuja getting up to 460.

Macroeconomic implications

Crude oil sales hold great significance for Nigeria’s economy. Here’s why: beyond revenue earnings, the country relies heavily on it for foreign exchange earnings. Given the unstable nature of the Naira, anything that affects the inflow of FX into the country trickles down to the other sectors. And most importantly, the oil and gas sector of the country controls the other sectors: when the revenue from crude sales dips, the other sectors shrink.

For instance, the last recession Nigeria slipped into — its second in less than five years — was caused intricately by low revenue from crude sales due to the oil price crash brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. The same could be said of the preceding one which left many states unable to pay salaries. This inability to carry out a basic function of government like payment of salary when federal allocation tanks speaks of the apron-string-like relation between the federal and most state governments in Nigeria.

Prof Adeola Adenikinju is the Director, Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law (CPEEL), University of Ibadan. For him, losses like this do not only incapacitate the government from carrying out its responsibilities and investing in infrastructure, it affects the exchange rate.

If the oil bringing the foreign exchange is impacted “that means the exchange rate will be impacted upon and that will affect the cost of production in the economy,” Prof Adenikinju says. “Anytime we have leakages in the value chain of production, in particular, it means the economy, even of the states, are affected.”

To mitigate this, the industry players and the government need to invest more in the sector’s infrastructure. “That some of the issues which led to the loss happened repeatedly means stakeholders in the industry have not done enough,” he said while emphasising that anyone found sabotaging the sector should be dealt with seriously so as to set good precedence.

Oil companies working in local communities must develop good relations with them. Having good relations may be complex but being socially responsible and constantly taking steps to avoid destroying the environment and taking quick actions to mitigate the impacts when it eventually happens, are concrete steps that could really break down the complexity, says Prof Adenikinju.

This story was produced under the NAREP Oil and Gas 2021 fellowship of the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism.

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries