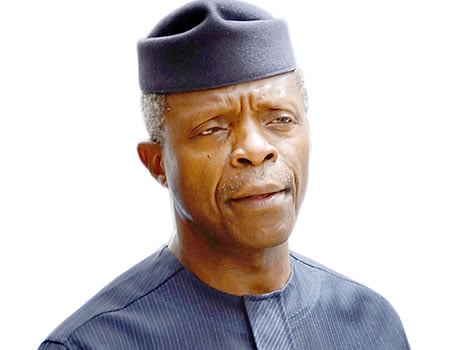

APPALLED by the ceaseless divisive and provocative utterances in the polity in recent times, Vice President Yemi Osinbajo drew a line on hate speech last week. Hate speech, he stated, was equivalent to terrorism and would be appropriately dealt with by the Federal Government. Relying on the provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (As Amended) 2011, Osinbajo said that hate speeches were being intentionally made to intimidate the population. He said: “The Federal Government has today drawn a line on hate speech. Hate speech is a specie of terrorism. The Terrorism Prevention Act 2011 as amended defines terrorism as an act deliberately done with malice which may seriously harm a country, or is intended or can reasonably be regarded as having been done to seriously intimidate a population. Silence in such situations can only be seen as an endorsement. Hate speech and the promotion of same through history, from Nazi Germany and the extermination of Jews to the Rwandan genocide, succeeded in achieving their barbarous ends by the silence of influential voices. The silence of leaders at this time will be a grave disservice to our country, its peace and its future.”

It is indeed a nation intent on self destruction that would treat hate speech with levity. If anything, the horrendous experiences of Nigeria’s First Republic culminating in the 1967-1970 Civil War should cause the current apostles of hate speech across the country to pause for a reflective, sobering second. As noted in folk wisdom, while the onset of a rebellion may indeed be tolerable, its end is always catastrophic, which is why a Nigerian proverb warns cripples crying for war that they will be the first casualties of the rebellion that they advocate. And while ethnic slurs have persisted over time (“The Igbo are people who eat stone without drinking water; the Yoruba are eaters of oily soup; Gambari kills Fulani, case closed”, etc), such slurs have assumed a more violent character in recent times and are more than micro aggressions. In this regard, we find the government’s concern about hate speech commendable.

Yet it is unwise to ignore the fundamental issues behind the current regime of hate speech in the country, including the failure of unification. For one thing, however hard it may try, the current administration would always have a hard time persuading Nigerians that it is committed to fostering harmonious coexistence among the ethnic nationalities that make up the country. This is not only because of the unprecedentedly sectional appointments that it has made so far but also because of its reactions to the genuine complaints by aggrieved Nigerians. By any standards, the statement that those who gave President Muhammadu Buhari five per cent support could not in all honesty expect to be treated like those who gave 97 per cent support qualifies as hate speech.

More fundamentally, the hate speech which the government is justifiably concerned about draws its inspiration from the blatantly lopsided and iniquitous structure which the country currently operates. If, within a supposed federation, the people that make up the component states are not in charge of their own economic fortunes, hate speech can only continue to thrive. Indeed, the current ‘feeding bottle’ federalism practised by the country makes hate speech both attractive and compelling, not least because those who feel that their rights have been circumscribed by a hostile national apparatus cannot be expected to keep quiet when they have been reduced to vassals, if not slaves, of a behemoth and unproductive centre. Thus, while going after the promoters of hate speech, the government must actively create an environment that discourages hate speech and animosity. The way to do this is by embracing the restructuring imperative.

The foregoing is of course not to suggest that the extant laws that deal with incitement and other crimes should not be taken advantage of by the government. However, if past experiences in the country are any indication, the point cannot be overemphasised that the government must not hide under the proposed law to crush or clamp down on perceived political foes. We believe firmly that clear distinction must be made between hate speech and free speech as enshrined in the statute books. This is admittedly a delicate exercise, but that is precisely why there is an institution called the government. Hate speech must not be equated with criticism, however strong, of the government in power. This point must be borne in mind if only because any party in power today can become an opposition party with time, and the nation cannot afford to institutionalise political persecution under the guise of addressing hate speech.

Needless to say, the government’s proclivity for not implementing the law to serve as a deterrent to offenders needs to be shelved if the fight against hate speech in the country is to yield fruit.