The Dangote refinery is an ambitious project. It has been seen as the answer to the many questions around Nigeria’s oil and gas sector. The woes of the sector will disappear once the project becomes operational, the government thinks. But, really, will this massive project solve all of Nigeria’s energy woes?

Deep-seated problem

Nigeria’s energy woes are well documented. The oil and gas sector, especially the downstream sector, is beset with deep-seated corruption and nepotism, making the sector largely inefficient and sub-optimally harnessed.

One of the most significant issues in the sector is the state of the country’s four state-run refineries: two in Port Harcourt, one in Warri and the other up north in Kaduna.

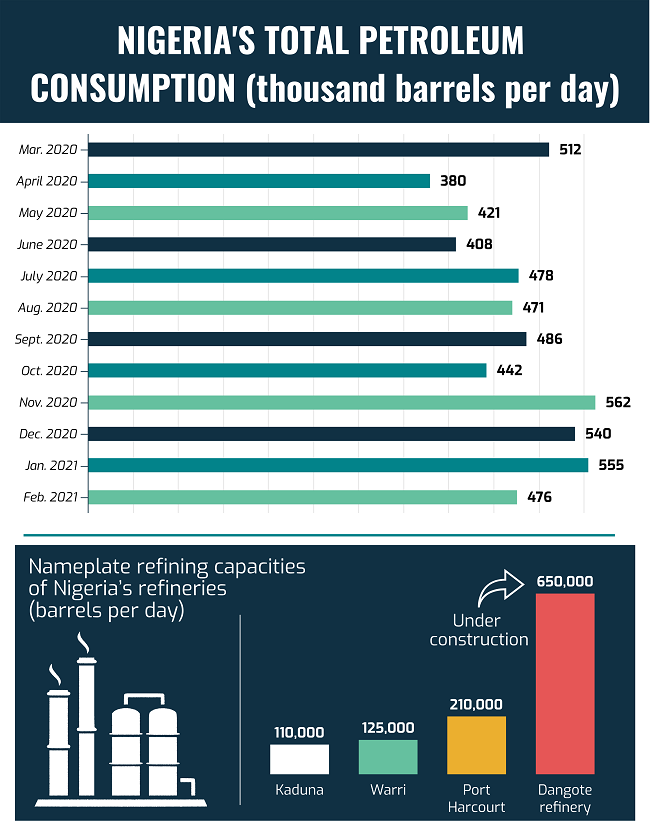

Established in 1965 and 1989, respectively, the two Port Harcourt refineries have a combined refining nameplate capacity of 210,000 barrels per day.

The Warri refinery was established in 1978 with a refining nameplate capacity of 100,000 barrels per day. But it was debottlenecked to 125,000 barrels per stream day in 1987. The Kaduna refinery has a nameplate refining capacity of 110,000 barrels per day. What this means is that the four state-run refineries in the country have a combined nameplate refining capacity of 445,000 barrels of crude oil per day.

On the other hand, Nigeria’s average daily petrol consumption is at about 476,000 barrels per day as of February 2021, just below 555 thousand barrels in January of the same year. What this means is that even if the state-run refineries were to run at 100 per cent of their nameplate capacities, they would still not meet local demand for petrol.

However, hoping that the refineries would run at their full capacities is a somewhat extreme hope given that for decades, they have not run at half their capacities and have been running at a loss.

For instance, the refineries cost Nigeria N148 billion in expenses, but produced only 38,977 metric tonnes of crude between June 2019 and June 2020, gulping an operating deficit of N62 billion, the NNPC said in its June 2020 report. Sadly, without refining even a litre of crude oil, the Warri and Port Harcourt refineries respectively gulped N42.1 billion and N43.8 billion from Nigeria’s treasury.

The NNPC’s excuse has always been that the refineries were undergoing maintenance. But many Nigerians have queried how long the maintenance would last, given that the same maintenance was on the lips of government officials when the current government came to power in 2015.

Recently, the federal government approved $1.5 billion, a large part of which was borrowed, for another round of turn around maintenance for the Port Harcourt refineries, coming after a series of maintenance in the past 25 years that have cost the country well over $25 billion. At best, it is an optimistic move and at least a policy summersault: the federal government had said it would dispose of the refineries to fund the 2021 budget.

Recall that the Port Harcourt refineries were sold by the Bureau of Public Enterprises to the Aliko Dangote-led Bluestar Consortium for $561 million in May 2007 during the tenure of President Olusegun Obasanjo. But the consortium pulled out of the deal later in July of the same year due to public outcry over the sale and the disposition of President Umaru Yar’Adua, who succeeded Obasanjo.

How the Port Harcourt refineries turned from being sold for $561 million to now being rehabilitated for $1.5 billion is a miracle many Nigerians are yet to understand.

Groundbreaking project

Sitting on a massive land area of approximately 2,635 hectares in an Export Processing Zone — about six times the size of Victoria Island, Lagos — the Aliko Dangote’s refinery is coming on stream with so much hype and hope. It is expected to be Africa’s biggest oil refinery and the world’s biggest single-train facility. Its installed capacity to refine 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day is enough to meet Nigeria’s daily demand of all refined products and also have a surplus of each of these products for export.

Recently, the project hit a milestone amidst fanfare when it received the world’s largest crude distillation column. Analysts say the processing tube is as long as a football pitch and has the weight of about 320 elephants.

The $12 billion project is expected to create a market for $11 billion per annum of Nigerian crude. Interestingly, it is designed to process the Nigerian crude with the ability to also process other crudes, Dangote Group says.

On unemployment, which, sadly, has continuously gone north, the project promises to aim an ambitious shot at mitigation. Group Executive Director, Strategy and Capital Projects, Dangote Industries Limited, Mr Devakumar Edwin, recently said the refinery will create direct and indirect jobs for at least 250,000 Nigerians when completed and fully operational.

Beyond one giant project

With the hype and hope, many Nigerians already think the project would bring a lot to the table so much so that it would reduce the pump price of petroleum products but Edward Obi, the National Coordinator of National Coalition on gas flaring and oil spills in the Niger Delta (NACGOND) thinks otherwise. “Of all things, the refinery will not solve the problem of how obfuscated the sector is: the lack of transparency, accountability, the domineering stature”, he said.

He emphasised that “it is the same cost of crude and whether you are refining or not, you will have to pay the market price for the crude.”

Deregulation of the Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) market is a big issue in Nigeria. It’s so deep a problem that it has become a tool with which to score political points or play opposition politics. And the government, past and present, have failed to confront it head-on. In 2012, the government of the then President Goodluck Jonathan made attempts to remove the subsidy. But the move met stiff opposition which later snowballed into the infamous Occupy Nigeria protest. It would later become one of the major talking points during the electioneering campaign which ushered in the present All Progressives Congress (APC) led federal government.

About a year ago, the present government announced the removal of fuel subsidy, citing its inability to continue spending huge amounts on it. It actually came at a time when the crude price was low, so it didn’t bother most Nigerians. But as crude prices picked up, it started biting hard as the pump price of fuel started going north. Then the government resumed the subsidy payment secretly, which is currently blighting NNPC’s books.

The question of deregulation has never been that of the need but of the will. Will the government muster the political will to stop the payment entirely when the refinery comes on stream hopefully in 2022? An electioneering campaign year? Will the opposition not play politics with it?

Of the major problems of Nigeria’s downstream sector, weak institutions is chief, says Zakka Bala, a vocal oil and gas expert and social commentator. The hope the Dangote refinery brings is refreshing but relying on a single project to rescue the oil and gas sector of the world’s 13th-largest crude producer points to the height of systemic and institutional failure, years of neglect that has riddled the sector and its damming frailty, he says.

“It shows the institutions established to run the sector smoothly has failed, largely not because of the lack of qualified personnel, because a corporation like NNPC, I am sure, has among the best manpower the country can offer; but I think it is because of political interference and unwillingness to make things right.”

For Obi, the refinery is a private business and the government should be less ecstatic about it.

“Nigerians should be carried away if the $16 billion which the Nigerian government claims to have invested into the maintenance of refineries had yielded the desired results. All we know is that it’s still at loss in spite of that investment.

“Nigerians should only be happy if the NNPC makes its books and accounts entirely public and become transparent; let Nigerians know what exactly we are exporting every day and what we are gaining from it and at what rate of exchange. Then Nigerians would be happy”, Obi said.

The import substitution drive of the Nigerian government has the refinery around it. It said it would cut the foreign exchange and save Nigeria about $8.7 billion the country spends annually to import refined products. This would eventually reinvigorate the ailing economy. But an analysis by The Africa Report found otherwise. There is a steep opportunity cost.

Here’s how: to satisfy the refinery’s feedstock locally, as Mr Sylva has promised, the country would have to supply well over 471,000 barrels which is the equivalent of Nigeria’s daily demand. This will save the nation about $8.7 billion per annum but it also means the country would lose at least $11 billion of forex earnings a year — an amount estimated to be about a third of the country’s total annual forex earing. That is at an average cost per barrel of $64.

On the other hand, if Nigeria’s leadership is bold enough to end the obscure fuel subsidy regime, the country would be able to save about $3.85 billion annually — this was the amount the country paid for subsidy in 2019. This would then bring the total savings to about $12.55 billion just above the estimated $11 billion of lost forex earnings.

Monopoly is another issue of concern to Balla, even though he described the project as an institutional investment the sector lacked for many years. With the inefficiency of the state-run refineries, the market would solely be that of Dangote when the refinery comes on stream, hence the need for a strong competitor to mitigate the negative effects of its monopoly. But he does not see a strong competitor soon coming up soon.

On the environmental aspect, despite the assurance of the Dangote Group that it is complying with environmental regulations in Nigeria and the best global standards, Obi expressed concern about the imminent impact, especially with the nature of Lagos.

“No matter what it does, as far as we don’t have an efficient rail system that will lift this and put on rails and then transport them to the remotest, the accidents that we always see, we would still see”, Obi told the Nigerian Tribune.

- This story was produced under the NAREP Oil and Gas 2021 fellowship of the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism.