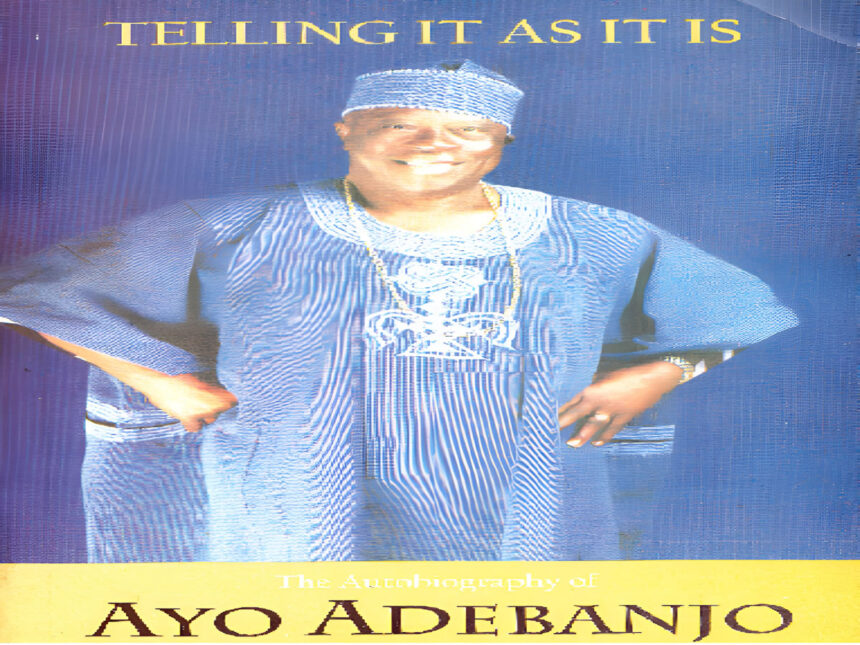

(Being an excerpt from Telling it as it is, the autobiography of Chief Ayo Adebanjo)

CONTINUED FROM YESTERDAY

Chapter 14

Afenifere, NADECO and the June 12 Struggle

There has been a lot of misconception and misrepresentation of the role of Afenifere in the nation’s political history. It is therefore important that I put the records straight, more so as a lot of people have labelled it as a Yoruba political organisation.

Afenifere is not any special organisation other than the Yoruba interpretation of the AG, and because AG cannot be defined as such, we spelt it out in the socialist policy of free education, free health services, integrated rural development and full employment. So, the Yoruba word ‘Afenifere’ means somebody who likes good for himself and for others; that was how the name came about.

Afenifere is not a Yoruba organisation; it’s just the name of the catchment area where it was founded, when it was founded and that is the AG. We have branches all over the country. The Middle Belt group was in alliance with us. We also had a minority group in the East (called the Calabar, Ogoja, Rivers State Movement). And that’s why we won election in all these areas. So, when people are accusing us of being sectional and tribalistic, they are just stigmatising us.

The NCNC which claimed to be national at that time hadn’t got the national spread in the legislatures of the country as we had. We were the government of the Western Region; we were the opposition at the centre; we were the opposition in the East; we were also the opposition in the North: the North led by Alhaji Maito; the East by Dr. S.G. Ikoku; and Chief S.L. Akintola leading the federal legislature. So, how much more national can you then be?

Our status is what we stand for; we are not standing for an election. The philosophy on which we stand is what any political party we support will preach. We are not changing our status. What we were founded for is what we are. We are not a tribal or cultural organisation. We can say we are culturo-political; cultural in the sense that we are from Yorubaland. But the real philosophy of the organisation is the AG philosophy. We wanted to interpret the philosophy to the people of Yorubaland at the time the AG was founded.

This means in the East there’s Afenifere; in the North there’s Afenifere; in the Middle Belt there’s Afenifere in their respective local parlance. In fact, they had the names they called them: in the East they were called the Eastern Mandate Union (founded by Arthur Nwankwo). When we were founding the Alliance for Democracy I explained all of this.

NADECO (National Democratic Coalition), on its own part, was a child of circumstance. Following the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential elections by Gen. Ibrahim Babangida, there were spontaneous protest demonstrations on the streets of Lagos, involving various civil society groups like Campaign for Democracy (CD), Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO) and the Campaign for the Defence of Human Rights (CDHR). Others were Afenifere, Movement for National Reformation (MNR), and Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP). These protests, which were spearheaded by CD, got the support of many ordinary Nigerians who saw it as an opportunity to vent their anger on the government for such insensitive action.

As a result, there was general disenchantment with the military over its role in aborting the return to democracy.

So, the desire of Afenifere was to restore sanity in the governance system.

In furtherance of the struggle for the return to democracy and the de-annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election which was won by Chief M.K.O. Abiola, the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO) was formed on May 15, 1994. As its name suggests, the body is a coalition of civil society groups and other political and non-political associations that were committed to this cause.

NADECO was to get rid of the military. And all of us who did not believe in the military came together. There was Afenifere. In fact, all those parties that claimed to be progressive came together, because we said if we were all fighting the military, we shouldn’t work at cross-purposes.

With the benefit of hindsight, some people now came to believe that the two-party system introduced by the Babangida government (that is, the National Republican Convention and the Social Democratic Party) was designed to fail ab initio. Their argument was hinged on the fact that those whom Babangida allowed to be recruited into the two parties were people who were pliable.

All the things we wanted done, many of them didn’t even understand, not to talk of believing in them. All they wanted was a platform to become minister, governor and all of that. But while we were talking to them about principle, it was after the whole thing had failed that many of them started to see what we too saw, just as it is happening now.

If you recall, there were two primaries, but the first primary elections were annulled. We expressed some reservations as a group at that point, but these were unheeded.

The army was in control, and those people who ought to have raised reservations were those people Babangida put forward for political positions. And at that time if you told any aspiring member not to go, he would say ‘oh, this man doesn’t want me to make a name because he has had his own time,’ until the whole thing collapsed.

I remembered someone, during the local government election, in my area. He said, ‘why are you bothering yourself about local government election? There’s no money in local government. The allocation of revenue is not there. They will give you a paltry amount of money, and you won’t be able to develop.’

So, all the collapse or the imperfections or inactivity of the local governments that you still see now started from the military. The military was merely allocating money to the local government councils to do whatever they liked. But local governments were controlled from the centre. That was the time when Augustus Aikhomu was in charge, and everybody was cooperating, because the military wanted to control the grassroots. That was why they were particular about controlling the local governments. Those who were beneficiaries of the largesse believed that was the best form of government.

In fact, when we were supporting Abiola at that time, we asked him, ‘are you sure this man is going to conduct this election?’ But we were misguided, thinking that he, being a close friend of Babangida, would know. Abiola then assured us that Babangida had told him that the election would take place. Then he said we could go on. We got that information directly from Abiola.

All we wanted was to have a civilian there, particularly when that civilian came from the west, more so because we had been complaining that no Yoruba man had been head of state. That was why we supported Abiola. When they annulled the election, it was in an attempt to pacify the Yoruba that they brought in Shonekan. But we said ‘no, the Yoruba we want is one of our choice and not of your own choice’.

In fact, within the military then there was no consensus. Abacha had his own ambition, that ‘if Babangida goes I must be there.’ So, in no time he toppled Shonekan. That was what gave birth to the regime of Abacha. The regime came to be an absolute military regime.

Before his decision to ‘step aside’ on August 17, 1993, Babangida had put in place an Interim National Government (ING) headed by Chief Ernest Shonekan with a 28-member cabinet having General Sani Abacha as its only military member. He then backed it up with Decree No. 61, which included a booby trap that ‘in the event of death or resignation of the Head of the ING, the most senior member of the cabinet should assume the reins of power.’

This provided an opportunity for Abacha, as ‘most senior member of the cabinet’ to instigate Shonekan’s ‘resignation’ and take over ‘the reins of power’ on November 17, 1993, following an earlier Lagos High court ruling on a suit filed by Abiola declaring the ING illegal.

Earlier on, Abiola was then in the NPN, while we were in the UPN. All that time we told him, ‘these people are just exploiting you,’ but he didn’t want to listen. All the time he said that Shagari promised him he was going to spend only one term, and that was why he supported Shagari. After the first term, they now asked Abiola, ‘where are you?’ It was then his eyes opened. Then he later left the NPN. That was it. In fact, he was so bitter against Chief Awolowo that it was he who raised the question of Maroko (360-plot land deal). But he got it all wrong.

I told some people at that time that the property I had at Surulere was a form of payment to me by clients whom I helped to recover their land from trespassers. So, this is just the tradition of lawyers. But Abiola did not know this and he used his Concord newspapers at that time to besmear the image of our leader. After some time, however, his eyes were opened. But when the question of election of Abiola came, we didn’t pay him in his own coins.

It must be stated that NADECO came to support Abiola, as a result of the annulment, not before the election. When I was arrested by the security agencies in the heat of the June 12 agitation, I told them the principle of supporting Abiola was not my own kettle of fish; that it could have been any other person, even an Abubakar or a Chukwuemeka.

The arrest was another twist in our struggle to actualise June 12. Three of us, Pa Abraham Adesanya, Alhaji Ganiyu Dawodu and I were arrested on June 17, 1996 by the police over the bizarre allegation that we were suspects in Mrs. Kudirat Abiola’s gruesome murder on June 4, 1996. This allegation was ridiculous because, prior to her assassination, we all (Afenifere leaders and Kudirat) had been in the vanguard of the fight for the restoration of Moshood Abiola’s mandate. In spite of this, however, we were kept in detention for over four months, often sleeping on bare floors.

I was part of Afenifere that joined the coalition of pro- democracy agitators. I didn’t join NADECO as an individual, I joined the group fighting for democracy and for the removal of the military. Our own organisation was in the forefront. We were using Afenifere at that time because the AG and other political associations had been banned. So, it was that cultural and political organisation that we used to form NADECO with other parts of the country.

NADECO had the name for being in the front line in the fight for democracy. So, for all others that joined we didn’t discriminate against them. Once we all agreed that the military must go, everybody came on board.

For those who were saying NADECO was fighting a Yoruba cause, it was after the annulment that they said those who remained consistent against the annulment were the Yoruba. But I insisted that that was not so.

When the annulment was made, Adamu Ciroma also said, ‘Abiola won fair and square, I was one of those who were fighting for him.’ But where the Yoruba became the only ones who remained in NADECO was where the Yoruba became consistently constant. When the others chickened out, we remained. That was why I answered those who were accusing NADECO of being a Yoruba organisation: ‘You are not being fair to yourselves. If you have been accused of being inconsistent and you chickened out in the battle comes, why should you blame those of us who continued the fight? If we too had chickened out the way you did, there would have been no NADECO, there would be no getting rid of Abacha.’ By the time the battle was fierce, all those who formed NADECO chickened out; those who now remained championing the cause were from the minorities and the Yoruba. The Yoruba were in the majority, which was what gave them the leeway. The antagonists just gave us that name to justify their cowardice.

Our stand in favour of Abiola spelt this out completely, because everybody in Nigeria knew that Abiola was our political enemy. He was one of those who prevented Chief Awolowo from becoming president. But that didn’t disturb us because the teaching that Chief Awolowo gave us was that ‘anything that is good for Nigeria, no matter who initiates it, you must support it. That was the principle under which we operated.’

When Shagari sent Abdurahman Shugaba packing in the northeast, we were vehemently opposed to it and fought the injustice. During the Tiv riots, it was the Yoruba that rescued Joseph Tarka. Even when the NPN deposed Balarabe Musa as Governor of Kaduna State unjustly, Chief Awolowo sent Chief G.O.K. Ajayi and myself to go and defend him. Therefore, our fight for democracy has been irrespective of whose ox is gored.

The most significant achievement of NADECO is the fact that it ended military rule. We fought them to a standstill. It was however not those who fought for it that got into power thereafter. That’s one of the regrets. In fact, it was those who supported Abacha that became governors and other political leaders because they now had money. Even one of the most prominent members of his government, Ebenezer Babatope, moved the motion that Abacha should rule forever!

When it comes to the question of being labelled, many of these people have forgotten their roles, that many who were known to be progressives in the days of the AG or during NADECO became ministers under Abacha; this is the undoing of L.K. Jakande for joining the Abacha government. It ruined his reputation forever. And Babatope’s. It brought them down. We warned them.

I remember Babatope coming to my office in Western House over this matter, saying ‘if you ask us to go we would go.’ Even when they started to kill our people in Lagos and we warned them that they would get killed and asked them to get out of the government of Abacha, they didn’t. Even Chief (Mrs) Mojisola Osomo who was recommended by Papa Ajasin, and whom we saw as his protégé, all refused to adhere.

Take also the case of Dr. Olu Onagoruwa, who had warned in 1994 (front page of Daily Times) that if Abiola had been allowed to rule, Nigeria would have gone in ruins. If I remember Onagoruwa’s position very well, he was in NADECO with us. Papa Awo had such confidence in him that even before 1979 when we were asked to nominate candidates for electoral positions, it was he (Papa) that nominated Onagoruwa to represent the UPN.

During the NADECO days when Anthony Enahoro was our leader, we were all meeting together in Rewane’s house. That was when Abacha came into power with Oladipo Diya, and before Onagoruwa was made a minister. We were asking for restructuring and the convocation of a national conference when Diya detained me in Abeokuta on assumption of office.

Onagoruwa was there and he asked, ‘Haa! why did you detain this man?’ ‘What is the complaint against Chief Adebanjo?’ Onagoruwa asked, ‘why all the fuss about this man?’ He said, ‘that is the man o!’ By the time Diya said he wanted Onagoruwa as the Attorney-General and we doubted whether he should accept, he (Diya) gave us the false impression that, knowing that we were the agitators for a national conference, by choosing him as a minister, it meant that the government was going to have the conference. That was the bait.

So, when he got there now and he was sitting under Abacha, and we did not see the prospect of any national conference taking place, and asked him to resign, he said if he should resign, that government would not last one day longer. He made that mistake. Later they sacked him and also killed his son. When all these things happened to him, he was no longer associated with us.

Sometimes they say I am too rigid, but this has always been based on principle. Take the case of Ebenezer Babatope for instance. As one of the young disciples of the late Chief Obafemi Awolowo, whom I held in high esteem, his reactionary behaviour during the Abacha regime and his later joining of Obasanjo’s party (PDP), greatly disappointed me. This is responsible for my cold attitude towards him ever since.

For instance, when Obasanjo wrote ‘Not My Will’, in which he maligned our leader Chief Obafemi Awolowo, he countered it with a scathing rejoinder in his book, ‘Not His Will’. This, I thought, was a demonstration of his continued loyalty to the leader; but having now jumped ship, he can no longer claim to be one of us.

I can’t see someone who says he is an Awoist and is comfortable with Obasanjo, Abacha and Babangida and keep mute. He moved the motion that Abacha, despite all his atrocities, should continue in office. Is that consistent with a progressive person? I have been in this party now for over 65 years and people know me for the principles I stand for. Whether we won election or not, I have remained consistent. It was when we won the election in the UPN that Babatope was employed as Director of Organisation, and when the military took over, he chickened out, and still wants to be accorded the respect of an Awoist. This I object to.

He feels very uncomfortable with this, and often goes about maligning us by saying that we don’t have a forgiving spirit. But people should ask him whether there was anytime he came to Afenifere meeting and we walked him out.

When there was a crisis in the party and he said he was going to the United Kingdom to study law, and sought financial help from me through his wife, I readily came to his help, not with a loan that he asked for, but with what I could afford to give. This was in keeping with the tradition of our party where the leaders were very supportive, just as Chief Rewane also supported me by paying my house rent when I was in detention.

What Babatope expected of me was to facilitate a return to his old position in the party which I turned down, because somebody else had occupied that position after he left. Ayo Opadokun’s son was his assistant who rose with Afenifere and NADECO, and I informed him we couldn’t have reserved the position for him. That has been my problem with him.

Chapter 15

My position on the 2014 National Conference has been very clear. This is to the effect that President Goodluck Jonathan’s initiative in calling the conference is commendable. The quality of representation was quite high and evenly spread. The recommendations made by the conference were far-reaching, and, if implemented, would solve many of our problems as a nation.

There is a saying that half-bread is better than nothing. I am not one of those who make too much fuss on the word ‘sovereign,’ because what sovereignty means is that whatever decisions are taken at the conference are not subject to any amendment except to a referendum. But if we did not use the word ‘sovereign’ and after the conference we see that there was nothing wrong and we get what we wanted, I believe that we shouldn’t quarrel about semantics. My thinking was that we should allow the subject to take place first, and then we can be talking about the predicate, whether sovereign or not.

The word ‘sovereignty,’ which I even argued with Obasanjo, means that it rests with the people. All we were saying was that we didn’t want the government to handle it the way they did the 1979 constitutional conference, where Obasanjo inserted the Land Use Decree, which was never recommended, in the decisions, and then another military administration came and amended the constitution. We didn’t want that. That was why we condemned the present (1999) constitution as a military constitution. If it is going to be the people’s constitution, only the National Assembly, and the people should say yes or no.

Even if we use the word ‘sovereign’ now, and you convoke the conference, let us have the subject first and people talk. Then we can debate whether there’s sovereignty now or later, so far it is a matter of execution of proceedings.

So, what I said about those who argued that we should make it sovereign was that we shouldn’t quarrel about that. Let’s have the conference first. Even the question of whether it should be sovereign or not was later dropped because we had pressure from all quarters that the conference should take place. After the pressure and the conference was held, the issue that arose again was whether the outcome should go to the National Assembly or not.

Many of us were opposed to the idea of the recommendations going to the National Assembly, because the National Assembly itself was part of the problem that we wanted to solve. That was our stand. Our belief was: let us first solve what we were going to sovereign upon and when we have it the debate would resume. At the end of the conference, we now agreed that our recommendations should only be subjected to a referendum.

Those were my expectations. Even up till now, I still earnestly desire that those recommendations should be implemented. I remember that before the election, one main reason our own group supported Jonathan was the promise that he would implement the recommendations. Although some people say that we shouldn’t rely on what he had said, my own take is that ‘here is somebody who says I will do. But Buhari says he has nothing to do with the conference.’ So, that was why I said ‘half-bread is better than nothing,’ and that was the basis for my support of Jonathan.

At least 80 per cent of my expectations were achieved during the conference. For instance, regionalisation of the police, devolution of powers, rationalisation of the local governments in each region. Revenue allocation (fiscal federalism) was reduced and passed on to the state, and local government was put under the state government. Central power was drastically reduced.

One of my very few expectations at the conference which was not achieved is regionalisation. This was because some minorities in the north felt that it is good for the people in the southwest to talk of regional autonomy. They argued that they were put under slavery in their region because they were treated like paupers (second-class citizens). That if they have their own autonomy, like having their own state, which would lead to creating more states, then we can talk of regionalisation.

That they have joined a region of their own choice on an equal basis. That was why, in the recommendation of the confab, we called for the creation of more states and put a provision that states of like minds can join together for common services. They can also pull out, if they like, by conducting a referendum. So, we made the recommendation for eventual regional autonomy. But that, for now, everyone should be free to say ‘I am in this or that region by having their local governments.’ Right now, what we have is the devolution of power to the states; whereas if we had regionalism, it would have been devolution of power to the regional governments.

We have a lot of lessons to learn from the First Republic in this regard.

The Independence Constitution we had was the type of federalism we wanted. To the extent that when we had self-government in 1959; in the north and two years earlier (1957) in the south, they all had their constitutions written differently. And that was how we carried on, and we would have had independence then but for the north which said they were not ready, and so we waited until they had their own self-government in 1959; self-governing regions then came together to have independence for Nigeria in 1960. That was what we had up to 1963 when Nigeria became a republic, because we had a really federal constitution. But with the 1966 coup, the military centralised everything.

TO BE CONTINUED TOMORROW

READ ALSO: Afenifere honours late Pa Adebanjo with public symposium

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries