Somewhere in southwest Nigeria, *Taye went into labour. It was her’s and Taye’s (her husband) second baby. Damilola, the older sister was expecting a baby brother. It was in the middle of the night, with the closest community health centre some 10 miles away.

“It wasn’t meant to be this way,” Taye sobbed, “we were supposed to be a family of four.” Nearby, Damilola, 5, played with sand, occasionally glancing at her mother, seated on the floor of the face-me-I-face compound she shared with 12 other families. She was trying not to wail out loud.

Taye’s baby chose to arrive two months earlier than the due date, her husband explained to relatives, clustered in the corner of the yard, wondering what could have happened. “She just said she was feeling pain in her stomach and we went to the hospital,” the husband managed to say, trying hard not to betray emotions. “You’re a man, you shouldn’t cry. If you cry now, what will your wife do? You’re meant to comfort her. Be a man you hear,” relatives and neighbours consoled.

At seven months pregnant, Taye, an asthmatic patient went into a premature labour and the only doctor in the community health centre had gone with an emergency patient to a hospital in another village. The patient had been hit by a drunk driver, his life hanging in the balance. Back home, auxiliary nurses were trying to save Taye and her baby’s life. According to report, Taye’s blood pressure had shot up unexpectedly and the baby was in distress.

Three and a half hours later, a weak Taye pushed out her baby, but the infant would not live. Part of the reasons given was that the community centre was not properly equipped to perform an emergency Caesarean Section that may save the baby, and that the nearest hospital that was equipped enough to cater for the mother and child’s needs was at least five and a half hours away and there was no vehicle that could take on the journey.

*Names in this story are changed to protect their identity

On April 4, 2017, the Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) dropped a bombshell. The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) had failed to remit over $21.8 billion (about N7.2 trillion) into the Federal Government account.

NEITI, from a series of its oil and gas sector audits it conducted, learned that the NNPC and its upstream subsidiary, the Nigerian Petroleum Development Company (NPDC), failed to remit over $21.78 billion and N316.1 billion to the Federation Account, and shared this in its Policy Brief released in April this year. Audits report shows, according to the transparency agency, that an outstanding $1.7 billion from a total of $1.8 billion was as a result of the transfer of eight Oil Mining Leases (OMLs) from Shell Petroleum Development Corporation (SPDC) and another $2.2 million from four other OMLs from the Nigerian Agip Oil Company to the NPDC respectively.

NEITI’s report added that about $148.3 million paid as cash calls on the transferred OMLs, in addition to about $1.5 billion legacy liabilities as well as about $15.8 billion that accrued as NLNG dividends between 2000 and 2014 were yet to be remitted to the Federation Account. All of these brought to a total value of $21.8 billion (N7.2 trillion) unremitted finances to the federation account.

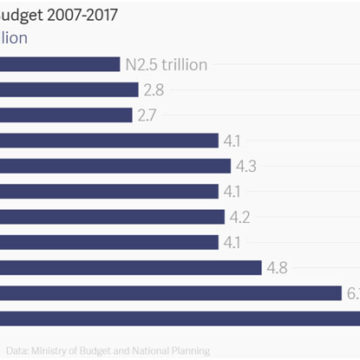

The unremitted N7.2 trillion is the total value of 2017 at N7.298 trillion, Nigeria’s single largest budget in 10 years.

With the N2.24 trillion, Nigeria could have provided infrastructures such as health, housing, road and power, water and education, four key infrastructures that could have contributed to poverty reduction in the country, she reasoned.

It will be recalled that the Nigerian government had budgeted N529 billion for power, works and housing; N85 billion for water resources; N81 billion for industry, trade and investment; N51 billion for health; N142 billion for education (and UBEC) and N94 billion for development of Niger Delta region (and Niger Delta Development Commission); as well as N262 billion in transportation, bringing the total projected investment to N2.24 trillion for 2017. These key investments in capital expenditure “could have helped contribute to the development and lifted millions of Nigerians out of poverty,” a development expert and CEO, Rimdinado International Ltd, Olusola Adetiba said.

Nigeria in poverty

Poverty still remains significant at 33.1 per cent in Africa’s biggest economy, according to the United Nations. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) puts the number of people living below poverty levels at 112 million in 2016, representing 67.1 per cent of the country’s total population of 167 million. Data shows that Nigerians make more than 10 per cent of the global poor, standing at one billion as at the same year.

The BTI’s Transformation Index for 2016 puts poverty rate in Nigeria at 76.5 per cent, as the country ranks 152 out of 187 in Human Development Index (HDI).

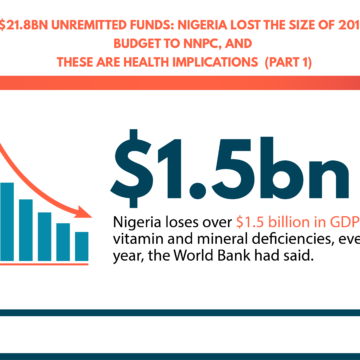

What unremitted billions, lack of infrastructure and poverty have in common

Lack of investment in economic and social infrastructure is costing Nigeria billions of dollars in revenue that could help improve and sustain the livelihood of the country’s citizens, experts are saying. With N2.24 trillion out of N7.2 trillion trapped in the NNPC, the implications are that Nigeria is unable to provide adequate infrastructures such as clean sources of water, health and education facilities, markets and proper transport access to its citizens, thus exacerbating poverty-induced consequences on Nigerians, and further increasing economic losses incurred by the country.

Infrastructure deficit widens the poverty gap, Kayode Ajayi-Smith Executive Director, Joint Initiative for Development said in an interview with this reporter. According to him, infrastructure deficit in education, health and sanitation would not only widen the income inequality gap, it will, over time, lead to increased violence in the country, considering that Nigerian population is made up of mostly the young people.

“The population in swamps is increasing and it is estimated to increase to 20 billion in 2050, most of them in developing country. If that amount of money is invested for instance in housing, it will reduce the potential of communicable diseases.

“You also know that our population is rising. If our population is rising and we are talking about achieving demographic dividends, we also need to think in terms of empowering women and girls because demographic dividends cannot be achieved without empowering women which means we need to invest in education,” he said.

It is estimated that Nigeria’s population will increase to over 400 million by 2050, which means if investments are not made in developing the country, the cycle of poverty will continue, which signals dangerous trends for the country, relative to unemployment, high increase in illiteracy and violence, Ajayi-Smith said.

Implications of NNPC’s unremitted fund on Nigerian’s access to healthcare

“Once there are deficits in health infrastructure, it will negatively affect access to healthcare services and thus patients that need care won’t get it and they will remain sick. Ill-health precludes people from working and thus they can’t make income, thereby propagating poverty,” Dr Michael Olugbile, Harvard-trained Public Health expert, explains what infrastructure deficit in health sector means to Nigerians living in poverty.

Top health and water-related issues in Nigeria

“Preventable or treatable infectious diseases such as malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea, measles and HIV/AIDS account for more than 70 per cent of the estimated one million under-five deaths in Nigeria,” UNICEF has said.

Malaria

Malaria in Nigeria is responsible for 60 per cent outpatient visits to health facilities, 30 per cent childhood death, 25 per cent of death in children under one year and 11 per cent maternal death, according to the Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health. The ministry adds that the financial loss due to malaria annually is estimated at N132 billion in forms of treatment costs, prevention and loss of man-hours, among others.

Malnutrition

Maternal and child mortality

Nigeria constitutes two per cent of the world’s population but contributes 10 per cent of the world’s maternal mortality, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) said in 2016. Almost a million children die yearly in Nigeria, following data from the UNICEF, which indicates that Nigeria loses about 2,300 under-five-year-olds and 145 women of childbearing age “every single day.” This makes the country the “second largest contributor to the under-five and maternal mortality rate in the world,” according to UNICEF.

“The unfortunate thing is that,” Dr Olugbile said, “it is the poor patients that usually don’t have access to healthcare and will be most affected by the deficit as the rich can afford to get services from elsewhere both within and outside the country.”

This report was made possible by the BudgIT Media Fellowship 2017