“I could see he was still battling with his emotions. As a medical doctor, I understood him perfectly. Every doctor knows and must have experienced the difference between “the best of available care “ and “the best of care.” Medicine is a calling built on the innate desire and tenacity to help others. It carries with it a great responsibility for the practitioner.

ASUU strike: Labour Minister takes over negotiation

“Since I came into the medical profession, the most nagging question I have had to ask myself and provide an answer to every time I attended to a patient, especially one whose well-being hung on my shoulders, was, “Have you given the best of care?” I would wake up in the middle of the night to review the patients I had seen during the day, especially the very serious cases. And for surgical cases, it was never over until the patient had passed through the crucial post-operative period. I have had to cancel planned journeys and vacations because of unanticipated post-operative events.

Am I alone? The answer is, No. Every doctor carries the burden of care of his patient with him everywhere he goes. He owes his patient two burdens of debt. The first is the debt he incurs the moment he accepts to care for the patient. It’s a professional pact between him and his patient. He can reduce this burden by ensuring that he is well trained and up-to-date with his skills and knowledge and by making himself available or providing someone to deal with expected and unexpected consequences of his intervention.

The Yoruba put it succinctly, “Onisegun bi oole wo mi san, fi mi sile bi ose bami.” This translates to, “Doctor, if you can’t heal me, leave me as you met me.” In short, “don’t make my condition worse.” Many of my colleagues pay a large chunk of their earnings to acquire relevant skills and knowledge, locally and internationally, to reduce this burden and be at peace with their conscience.

But there’s this other burden of debt, which the doctor often has little or no control over — the burden imposed by the society through its elected officials. In Nigeria little thought has been given to this. The elected officials determine how resources are allocated and managed.

This in turn determines the quality and quantity of the work force, the equipment and instruments available to give the best of care, the remuneration paid to all members of the hospital team and other important things necessary for the doctor to give, not just the best available care, but the best of care.

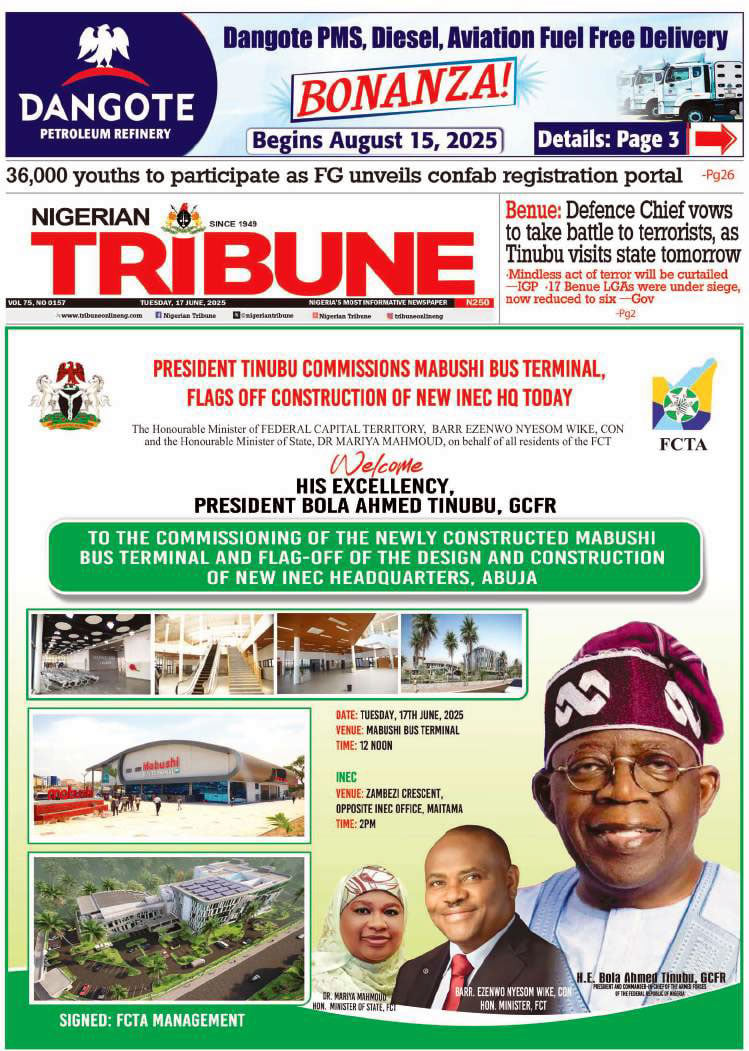

Do members of the society really have a hand in the election of its leaders? The answer is, No. Quite often, what we call “election” is synonymous with “selection.” Even the Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission has confirmed that this year’s party primaries were among the worst in the history of elections in our country. If the foundation is rotten, should we be surprised that the building is crooked?

Thus, in addition to carrying his own professional burden, the doctor is left to carry the burden of working in substandard conditions, often without the basic necessities such as water and electricity. Government hospitals charge fees that are far above what they pay to their own workers. Investigations are for the rich and the doctor, quite often, has to use his clinical judgement to decide on the final diagnosis in many cases.

Because he has to tailor his treatment to the size of his patient’s pocket, he may have to use less efficacious medications, if that’s all his patient can afford. Monitoring of treatment becomes a big challenge for several reasons. Many cannot afford transport costs because they’re jobless or owed several months of unpaid wages. And sadly, the various arms of government are the main culprits in this regard.

Chronic diseases are even a bigger challenge. Medications have to be taken on a daily basis. Since everyone taking one medication or the other still has to eat, compliance with the use of medications takes the knock. It’s often not used at all and when used, it’s irregular. The control of the disease gets out of hand. The glaucoma patient becomes blind and makes passionate, heart-rending pleas for the doctor to restore his sight. The diabetic is crying not to have his limbs amputated; meanwhile, his eyes are on his way to blindness. The hypertensive patient develops cardiac failure and requires more expensive medications to keep him alive.

The doctor inevitably carries all these suffering patients with him. The cumulative assaults on his moral and ethical values may make him less sensitive, thereby, losing the critical aspect of showing concern for his patient — a despicable situation, totally unacceptable to all patients. It’s a negation of what the Ijebu refer to as “aajo jowo,” (caring is a loftier goal than making money).

Their care and ultimately their life is his responsibility. Thus, the already overburdened doctor, adds to his worries the burden of the society’s collective guilt of not demanding from its elected officials a comprehensive account of their plans for their health, for not holding them responsible for their actions and inaction and for letting them get away with severe breeches of the constitution.

Many doctors are suffering in silence and quietly battling depression. Research outside the country has shown that doctors have the highest rate of depression and suicide of any profession. From newspaper reports, it would appear that Nigerian doctors share the same fate.

The amount spent so far on party primaries is scandalous. I beg the political gladiators from all parties to spare a thought for the suffering masses and ease the pains of medical doctors by coming to the aid of the needy during their electioneering period as a sign of what they plan for them if eventually selected.