“I have a fear that we might end up with tribes or clans forming their own parities.” This observation is credited to Dhiim Manyuon, from the city of Perth in Western Australia, in January 2002 about the politics in Southern Sudan. His piece was entitled: “Proliferation of Political parties: A Question of Constitutional Debate”. In terms of population, that country is less than the size of either Kano or Lagos State in Nigeria. In terms of geographical size, Southern Sudan is a little over the land mass of Taraba State, and because every politics is local, the scenario in the oil-rich, but currently strife-torn Southern Sudan has some semblance to that of Nigeria. The parallel of the Juba situation and Abuja is the number of parties and Nigeria’s 180 million human population.

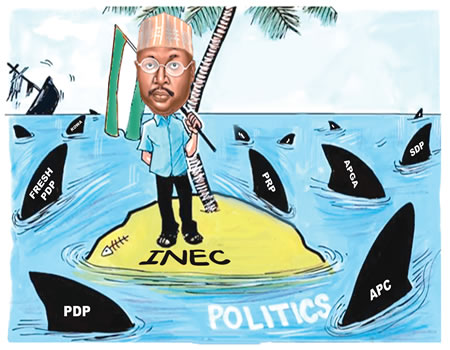

The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has already warned the electorate to brace up for the possibility of contending with an avalanche of parties in the 2019 elections. Twenty-seven new ones have since acquired the full status of new parties, with 80 associations on the verge of scaling the hurdle in their bid to join the fray. When Nigeria restored civil rule on May 29, 1999, five parties blazed the trail: the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Alliance for Democracy (AD; All People’s Party (APP), National Conscience Party (NCP) and the Peoples Redemption Party (PRP).Bereft of any clear-cut ideological underpinning, the parties soon underwent internal restructuring in terms of membership leading to transformation into new names with the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA), Labour Party, the Accord and the others shooting out frontally like supersonic jets in the political space. While the AD was castrated by powerful elements within its fold in collaboration with powerful forces in power in control of the PDP, APGA, LP and Accord became the beautiful brides. However, the phenomenal following of APGA built on the goodwill of the late war lord, Chief Odumegwu Ojukwu has paled almost into insignificance as it controls only Anambra State. Thanks to weird political realignments that shot at the soul of the party. For the Labour Party, the exit of the immediate past governor of Ondo State, Dr Olusegun Mimiko literally marked nunc dimitis of the party, just as the Accord is suffocating after another political titan, Alhaji Rashidi Ladoja finally decided to throw away the baby with the bath water. All these remote and immediate factor factors, especially ulterior pecuniary interests have culminated in and bolstered what Dr Remi Aiyede, of the Department of Political Science at the University of Ibadan, aptly captured as the proliferation of political parties.

However, some other individuals think the trend is more about constitutional and legal framework, coupled with the issue multiparty democracy, which is against any form of a short-circuited political arrangement. First, the 1999 Constitution guarantees the Freedom of Association. Second is the judgment of the Court of Appeal, obtained in 2002 by the late celebrated pro-democracy and rights activist and lawyer, Chief Gani Fawehinmi against perceived intention of the Dr Abel Guobadia-led INEC to operate a grossly regulated the political space. In a post-judgment comment on the essence of the Court of Appeal verdict and the future of Nigeria’s democratic process, Fawehinmi had said: “Apart from declaring the contested guidelines and sections of Electoral Act, 2001 unconstitutional, the Court of Appeal went ahead to hold unequivocally that associations that satisfy sections 222 and 223 are automatically qualified as political parties under the Constitution.”

Excited by the judgment, a critic had described perceived the recalcitrance of INEC to comply with the judgment, this way: “While the Court of Appeal opens the door of political incarceration, INEC is hell-bent on locking the iron-gate of political imprisonment. Ordinarily, INEC officials should celebrate the judgment of the Court of Appeal. But INEC mourns while the people rejoice. It, therefore, raises the question: whose interest does INEC serve – the interest of the people or the interest of power-wielders who are bent on preventing the emergence of credible and formidable opposition political parties in the contest for power?” A Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN),Femi Falana, also recalls Fawehinmi’s achievement through that historic Court of Appeal judgment thus: “Apart from leading a campaign for the restoration of civil rule, Gani spearheaded the effort that led to the expansion of the democratic space by ensuring that the stringent conditions for the registration of political parties designed by INEC were declared illegal by the court. Unfortunately, political opportunists have taken advantage of the liberalised atmosphere to register all manner of political parties. At a time that most Nigerian politicians were coming together on the ground of ethnicity, religion and other sectional interests, Gani set up the National Conscience Party (NCP) whose motto is ‘the abolition of poverty’ and whose manifesto is anchored on a welfare programme for Nigerians. But the enemies of our people dismissed the programme on the grounds that the state could not fund a social welfare programme. That is still the sing-song of the country’s bankrupt governing class.”

Section 153(1)(f) of the 1999 Constitution establishes the INEC, which by the provision of 153(2) is empowered to exercise the powers as contained in Part 1 of the Third Schedule to the Constitution. According to Item 15, Part 1 of the Third Schedule to the Constitution, INEC is empowered to carry out three principal functions: (i) Organise, undertake and supervise all elections provided for in the Constitution [item 15(a)]; (ii) Register political parties in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and an Act of the National Assembly [item 15(b)]; (iii) Arrange and conduct the registration of persons qualified to vote and prepare, maintain and revise the register of voters for the purpose of any election under the Constitution [item 15(e)].

In the outgoing year alone, 27 new parties were registered by INEC, with the first set released on July 7 comprising the Young Progressive Party (YPP), Advanced Peoples Democratic Alliance (APDA), New Generation Party of Nigeria (NGP), All Democratic Peoples Movement (ADPM) and Action Democratic Party (ADP). With the latest registration, there are now 45 political parties in Nigeria. The latest approval consisted of 21 parties, including the All Blending Party (ABP), All Grassroots Alliance (AGA), Alliance for New Nigeria (ANN), Abundant Nigeria Renewal Party (ANRP), Coalition for Change (C4C) and Freedom and Justice Party (FJP); Grassroots Development Party of Nigeria (GDPN), Justice Must Prevail Party (JMPP), Legacy Party of Nigeria (LPN), Mass Action Joint Alliance (MAJA), Modern Democratic Party (MDP), National Interest Party (NIP), National Rescue Mission (NRM) and New Progressive Mission (NPM). New Progressive Movement (NPM), Nigeria Democratic Congress Party (NDCP), People’s Alliance for National Development and Liberty (PANDEL), People’s Trust (PT) and Providence People’s Congress (PPC) were also registered. Also on the list are Re-Build Nigeria Party (RBNP), Restoration Party of Nigeria (RP) and Sustainable National Party (SNP). In effect, 67 parties are already preparing for the next round of elections, about one and half decade after the commission de-registered many others before the Court of Appeal reprieve. There is yet another association called the Nigerian Intervention Movement (NIM) being championed by Chief Olisa Agbakoba and a number of other prominent individuals.

In Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, hitherto a revolutionary political movement against apartheid, is believed to have been founded 1912. It led South African to independence and has remained the ruling party in that country. The old National Party is generally believed to have been formed by a splinter group from the Movement to form the governing South African Party in 1913, known for its racial discriminatory and repressive tendencies. In the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party is believed to hold the record of the oldest political party in the world. The Democratic Party of the United States, was formed in the eighteenth century, though those regarded as modern Democrats say the party birthed in 1828, while the rival Republican Party emerged in 1789.

Beyond those legendary records regarding their formation, of relevance is the classic emotional attachment and affiliation of their members. This can be attested to by lawmakers elected on their individual platforms. For example, John Dingell served an uninterrupted 59 years and 21 days under the banner of the Democratic Party in the United States Congress before he retired. Both Thad Cochran and Don Young of the Republican Party served for 44 years each as lawmakers. Their consistency in terms of political affiliation in spite of the occasional setbacks for their parties at different presidential elections is a at variance to the political somersault often embarked upon by Nigerian politicians who prefer to always identify with the winning party. There issues of ego, need to use parties as bargaining chips by the founders bent on expanding their economic empires. So, the emphasis to float parties are not altruistic but based on using them to seek political patronage either at the dawn of elections or at post-election periods. Party manifestoes are mere about sloganeering as they are designed to serve as conveyor belt for personal ego and agenda.

In India, which is considered the largest democracy in the world, to quote Professor Ayede again, there are more than 1000 parties, with some of them operating at regional or provincial level. The Indian National Congress, formed in 1885 when that country was still under the British colonial masters, remains one of the oldest political parties in history. At post-Independent India in 1947, it became the dominant party and formed in Government at different times. However, in the country’s first general election in 1952, 53 parties competed. In 2009, more than 360 outfits entered the race with multi-party coalitions taking shape. However, prior to the mid-1960s, the Congress party, under the leadership of the then India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was the single dominant force in Indian politics, but its influence whittled down after the death in 1964 of Mr. Nehru, who had played a prominent role in the independence struggle and held the party together. Then came an era of amalgam parties in the late 1980s, which one Indian said: “It isn’t an ideal thing. Multiplicity of political parties confuses a lot of voters,” but with an explanation that India “can live with it because it doesn’t make a difference on the ultimate outcome.”

INEC guidelines on party registration

Way back in 2013, Comrade Goddey N. Ominyanwa had, in a article entitled, “Proliferation of Political Parties undermine national development”, warned against a huge harvest political parties. He believed the trend was fraught with danger for the diversity of the country. He noted: “If the political trends In Nigeria are not pruned, time shall come when every mushroom bodies or associations would metamorphose into political parties In geometric progression as it has been asserted that ‘a stitch in time saves nine.…In reality, Nigeria cannot only be a giant of Africa peripherally without being diplomatic in approach to sensitive issues such as proliferation of political parties in a depressed economy. Political parties should not be allowed on greediness and selfish interest of shylock politicians.”

But, does the legal and constitutional framework on the formation of parties responsible for the so-called proliferation? The existing practice is that a prospective party can only seek official recognition through the following process: have a name, logo, and acronym, which must not be similar to any known registered political party, or have any religious, ethnic, or sectional connotation); have a Chairman, a Secretary, National and State Executive Committee members – all officers must have been validly elected to provide INEC with the record of proceedings of the elections; a draft Constitution, draft Code of Conduct and Manifesto. The constitution should have provisions that deal with things like how elections are conducted, the administrative structure of the proposed party etc.); a draft Constitution must also reflect the Federal Character principle of the 1999 Constitution, which is that all leadership posts must reflect the Federal nature of Nigeria and should be representative of the various federating units of Nigeria; while the Headquarters of the proposed party must be located in the Federal Capital Territory – Abuja, as well as be present in at least 24 out of the 36 states of the federation. It must also pay to the INEC a non-refundable fee of N1,000,000 (one million Naira); obtain the appropriate form- FORM PAI, while within 30 working days, the proposed party must submit 50 copies of the completed form and 50 copies of the draft constitution and manifesto of the proposed political party along with all other required information. All these documentation must get the INEC within 30 working days, otherwise the commission has the power to terminate the application for registration, and the proposed political party will have to pay a fresh administrative fee of N1, 000,000.

Generally, Dr Aiyede says, in as much as the proliferation parties might be outright wrong once it is in tandem with the democratic values and ideals, there is a need to carry out some reforms capable of restoring sanity, voter confidence in the overall system. Citing the prevalent trend and practice in advanced democracies like US and India, he advocated a system that would discourage political gladiators and their parties from shortchanging the electorate. He says the number could create further confusion since all the names must be reflected on the ballot paper. On his part, a lawyer and human rights activist, Wale Ogunade, who is the president of the Voters Awareness Initiative, does not see anything wrong with the rising number of parties in the Land because the “the more the merrier. Nigeria is not unitary system, where people want to be caged as Ibrahim Babangida did through two political parties.” He said a lot of things were wrong with the existing parties, as they too domineering for personal reasons. “The 1999 Constitution itself encourages freedom expressions, freedom of association and by implication, freedom of movement and because of that, obviously there is the need for people to have various platform to ventilate their grievances both politically and socially. It does not matter now if people out of their own volition, now decide to come under one umbrella, or coalesce under one party but the issue is that they have the right to form groups and groupings of their own kind and that is why you would find out that several people in igbo land belong to several political parties and does not take it away from the fact that those people are autonomous. Again in Yoruba land too, no doubt some people may not be interested in the main political parties, which is APC per se and they may want to join political parties of their kit and kin., particularly in their various regions and in the North, no doubt, they are more united belonging to one but again, there are still splinters that do not form part of the PDP and other smaller political parties that belong to the Balarabe Musa stock. And even to me, we need more parties so that because if the current ones are indeed parties, they are to encourage ideals and good political ideas that would increase level of awareness in their various spheres of influence.”

But Chief Adedeji Doherty, an engineer and former governorship aspirant of the PDP in Lagos State, said the new parties constituted the hands of Esau and voice of Jacob. He said they were being planted by the ruling party to subvert the will of the Nigerians during the next general election.

“It is a plan by the APC to rig the elections. They own most of the new parties. The plan is to use then to make propaganda statements just before and after the elections,” he stated.

But, Patrick Kaiku University of Papua New Guinea puts the issue of proliferation in what he considers as proper perspective. He argues that the negative effects of proliferation of parties are wide ranging, with its most devastating effect on the political stability, a fundamental factor necessary for economic growth and development. Citing his country as an example, he noted that parties usually rich into emergency alliances at the threshold of major elections. His words: “Loosely-aligned parties are easily formed and launched with so much promise and fanfare. After elections, some of these parties simply disappear as quickly as they come in. These scenarios raise very pertinent questions: What should be the expected roles of political parties in PNG? Can political parties be accountable to the voting public when they are loose and disconnected from their electorate?”

He equally contends that the proliferation of political “parties and their short-lived existence in the electorate will only contribute to the lack of political party institutionalisation, apart from the fact that such parties are “usually fomented by urban-based elites, disconnected in most instances from marginal constituencies such as the rural areas. Such political parties are centralised and with limited association with developmental issues in the electorate they seek to field candidates in. This phenomenon gives rise to what has been termed “fly-in-fly-out” candidates.” This is because “electioneering for these parties is facilitated by an army of short-term election campaign managers,” leading to the voting public being “denied adequate information on the candidates and policy platforms of these parties. With limited information, there is no opportunity to assess the viability of political parties and a means to keep the political parties accountable for its election promises.”

Another major setback such multiplicity of parties beyond manageable number is what he described as its impact on the parliament. According to the scholar, at the level of national politics, parliamentary stability becomes the unintended casualty of unregulated proliferation of political parties, because of it fosters party indiscipline which usually contribute to instability. Above all, it is his submission that it also a measure of dearth of strong political beliefs based on well-grounded ideological convictions, thus the culture of “self-serving and opportunistic agents who merely form political parties out of convenience.” He advised that such parties should be encouraged to merge or consolidate their resources so as to reduce the policy platform bottleneck and voter confusion that usually characterise election periods.