MY reference to what is happening to the architecture of African cities commences with the proposed Atlantic City in Lagos, where I reside. This multi-billion dollar residential and business development, being built on 10 sq kilometers of land reclaimed from the Atlantic Ocean will provide luxury accommodation for at least 200,000 people, and employment opportunities for a comparable number. Similar up-market cities can be found in Kenya: Tatu City; Ghana: Hope & King (Appohoria); and Congo DRC: La Cite du Fleuve, all of which are being elevated, among others, to compliment the ‘Uprising Africa’.

While these developments are mostly executed by developers within the developed nations, I do not endorse the luxuries that go along with them, which are not only unrealistic but a consumer fantasy that measures their environment to a foreign pedestal without relating to the economic challenges of people within. Such examples include not accounting for poverty supported by informal living, or a population growth that remains unchecked but is a potential economic asset. While most African nations may have the funds to replicate developed nations’ cities, my fear lies in the inability to properly utilise vast human resources in the face of numerous economic challenges. A typical example is Kilamba City in Angola that people avoided because they found the upmarket accommodation, meant for thousands of people, not only expensive but also culturally out of place.

A quote from Shakespeare as far back as 1608: “What is a city but the people”, remains pertinent today. And this is a challenge to the development of our cities. Should we accept the replication of developed nation’s African cities? This has been a yardstick for our architecture and development. And, unfortunately for most African cities, such an architecture relies on building materials, finishes and components provided by developed countries. While this may be the way forward from a global perspective, the cost to most African nations must be considered. I do not accept that finishing materials and components that constitute over 70 percent of the building developments are imported. This drains our nations’ reserves and should rather be used for Research & Development (R&D) or introducing more consumables. How much longer will African cities be ‘importers’ of their architecture and to whose benefit?

If the intention of the global community is for all to become one people, race and culture, and thereby erasing our tradition and heritage, then we may continue with the trend. But the human development of Africa and of most African nations may then need at least another 50 years to catch up with today’s standard of developed nations. Expecting developed nations to remain stagnant while we try to catch up is highly unlikely, and this indicates that we need to develop a uniquely African solution for our cities. Until we collectively wake up to this reality, African cities will remain confused in terms of how they address the needs of their people, provide affordable humane shelter, jobs, adequate infrastructure, facilities and security and instead develop inclusiveness for growth in all aspects.

Sub-Saharan Africa is reported to be moving faster than the rest of the world in terms of advancing city development. Is this culturally being adopted or simply a means to checkmate poverty by over flogging developments that become dilapidated? We see this especially in housing developments that over a number of years become slums due to overpopulation, and accommodating excesses of unemployed residents which makes the management of facilities impossible given the rising cost of the imported components that are pegged against the dollar. Compounding this is that local currencies are devalued at least once if not more within a decade.

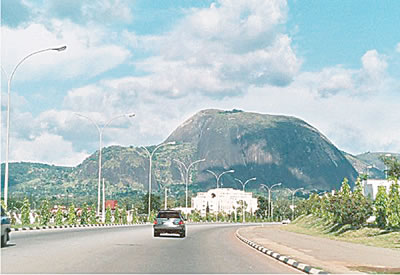

Africa’s population must be controlled and managed to ensure that its cities are not overstretched through informal settlements, and leaders do not use the migration of the people as a political propaganda. A recent World Bank survey reported that Africa’s cities are growing at 5.1 percent a year. The likes of Abuja, Lagos, Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) and Mbouda (Cameroon) are however experiencing between 6.2 and 7.8 percent growth annually. Such organic population growth, coupled with internal in-migration of rural to urban, needs to be checked by our leaders and Africa’s development teams. African nations must develop rural/urban cities that will provide the opportunity needed to provide R.I.C.E. (Research, Innovate, Connect, Empower). This slogan, adopted by the African Union of Architects at its 54th Council meeting in Lusaka, Zambia, in June this year, is reflective of what the union has embraced in the past few years of re-branding the African architect and architecture.

At the union’s recently concluded 55th Council meeting in Monrovia, Liberia, I humbly requested, in my short speech, as its immediate past president, that the President of the Republic of Liberia, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, adopt adopted R.I.C.E not only in her capacity as the present Chairperson of ECOWAS but as a respected member of the African Union (AU). To my delight, this adorable president requested that Liberian architects should research the historical Providence Island within the framework and to also innovate and connect with the government. She gave a reassurance that they would be empowered to engage with us. This is not just a statement of hope but a wake up call for developing African solutions.

Finally, our cities must see industrialisation as an important tool for ensuring sustenance. Our leaders should not only encourage industrialisation, but provide incentives to developed nations for relocating factories/industries to the continent and thereby providing employment for our teeming youth population. A UN Habitat survey reveals that Africa has the highest growing youth population in the world below the age of 30 years, yet the population remains uncontrolled and un-managed. If people ore happy, employed and not under paid, our cities will work; there will be less corruption and security challenges. The future of African cities remains in limbo and acquiring what we cannot afford continues to be promoted naively. What is new on the African cities architecture remains mixed with different euphoria pertaining to what is rising or what consumers find attractive. Where is the African culture and heritage headed? Cities are meant for the people and not the people for the cities.

Chief Tokunbo Omisore is the immediate past president of the African Union of Architects