When Aqsa Khan Nasar struggled to find her place in a confusingly violent world, growing up in Balochistan, southwestern Pakistan, she held onto her velvet kameez, seeking balance. She eventually began to fold velvet, the sense that she was missing the feeling of being at home in herself turned her to art. The compelling quality of her sculptures at once bring you before her home, sometimes into it, which is a sad irony as the artist herself turns away onto the next project; she hasn’t quite found it yet.

When Balochistan made international news early March, it was an attack on the Jaffar Express, a train passing through the Bolan valley to Peshawar in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Hijack footage from Balochistan Liberation Army, shot 90 meters above across an arid stretch of land, shows the rail blowing up then at least 400 passengers being corralled in circles. The BLA are one of the half dozen insurgent groups operating in southwest Pakistan. Decades of exploitative and oppressive treatment of the region, deeply rich in gold and oil deposits, proved perfect breeding ground for militant sentiment. The government immediately launched a joint operation to recover the hostages that lasted over 24 hours.

This iteration is the average imagery the Republic of Pakistan immediately conjures. It hovers within as well. In 2017, a bomb ended service in Khan’s home city of Quetta, killing eight. The routine horror was a lot to take in as a young Pakistani, life already had enough troubles in a region where 60% lived below the poverty line at any given time. Khan would relocate to the United Kingdom soon after.

‘No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark

No one would leave home until home is a voice in your ear saying- leave,now, I don’t know what I have become’

-Warsan Shire, Somali poet

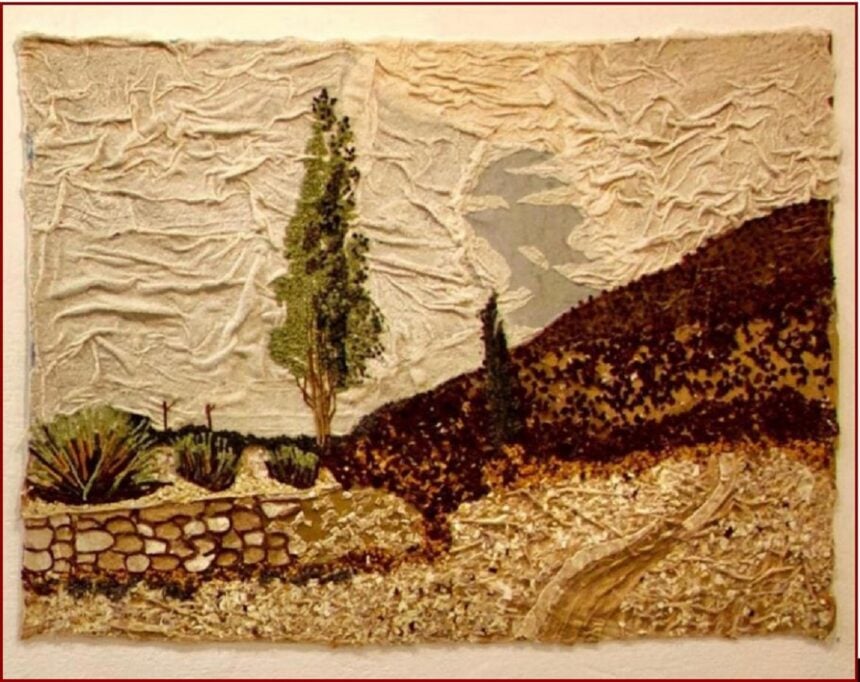

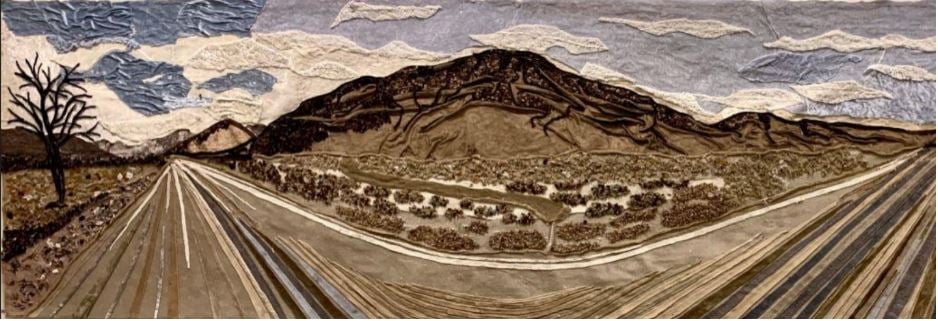

Rainy Birmingham would sway Khan down a path of unassuming activism. But we need to step back in time, back to Khan growing up in Quetta. Perhaps the hypnotic pull to Velvet, one of her earliest projects, is because we are made to look through soft, almost innocent eyes, at a part of the world we prefer to summarize with imagery such as arid and blowing up. The existence of the work is itself testimony to Khan’s deft. Her stone and chisel are velvet and thread, birthed through a blend of applique and layered collage techniques, methods that involve sewing or fixing different pieces of cloth onto another. The process is meticulously slow, and demands likewise perusal. What immediately distinguishes this textile landscape is its exclusive use of velvet, a very soft fabric common in decorative Pakistani clothing. It’s inherent sheen and pile respond dynamically to light, creating a rich tonal variation that mimics painterly effects, especially in shadowed areas like the hillsides, vegetation and clouded skies. The whole thing is kept up by a canvas to support stitching and structure. It would have benefitted from a single misaligned shape; the closely controlled crafting could easily undercut its conceptual roots, passing off as only decorative. It’s effect is potent nonetheless, tactile illusionism; it invites you to touch it, touch the smooth-coarseness, touch skin, see my real skin, not extremist, I am velvet, I am soft …

Khan met a dual personality in Birmingham; the UK artist from South Asia. This dual was burdened with the need to account for Western sentiment towards her home country, as well as growing awareness of the huge role her new residence played in making her home as turbulent as it is. Dasmaal unveiled a worldy, more provocative sculptor, a quality that hangs heavier when Khan delves into olfactory art. Dasmaal hangs like a tasseled standard, proud and uneasy. Drawing heavily from Pashtun marriage traditions shared across societies in Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, she illustrates the sameness of the people of core South Asia, now divided across European-drawn borders and increasingly spiteful toward the other.

So yes, Britain is roped in the story, Khan wishes its emblem were not on her wedding garment, snickering mere rows across from her country’s crested commitment to unity and sacrifice. But what better to convince amnesic spouses of the fidelity of your union? The people of core South Asia share a common Vedic ancestry, still evident today as these countries share languages and cultural norms. Due to centuries of invasions and cross-cultural encounters, the region was populated by a number of religions notably Islam and Hinduism. Following a failed rebellion, the British formally colonized India in 1857. As early as 1872, they redefined religious identities into political classes by including religious questions in censuses. The story of the deep rift among the people of the Indus valley, already existing across heterogenous lines, begins here. In ceding control of the subcontinent in 1947, the British delivered a divide-and-rule masterstroke on their collage nation, a move known simply as the Indian Partition. The Vedic people of the Indus valley, formerly clusters of cities and princely states, then became the British Raj. were now split in two; Hindu-majority Union of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. A move that displaced as many as 15 million and caused the death of one or two million, Hindus never making the flight from their homes in what was now Pakistan, fearing sectarian violence. A few million more bodies would fall when the violence did occur, culminating with the Hindu-centered East Pakistan seceeding in 1971 to become the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

In her 2022 United by Spices Khan knows exactly where to point accusatory fingers at for the vandalism of her home. This is where she introduces the olfactory dimension, with one lead tool; spices. In history and fictional worlds such as Arrakis, spices have symbolized wealth extraction by invading imperial powers. One of the pieces in this project is a reimagination of the British crown, made of cloves and cardamom. The imagery is simple and striking; the First World status the British enjoy today is directly at the expense of the future of the children of those who had beaten down two centuries ago, her future. Square on the crown she places a lookalike of the Kohinoor diamond, one of the jewels on the crown of late Queen Elizabeth, ‘taken’ from a deposed ruler in 1849 by the East India company.

Aqsa Khan, despite being in the first decade of her career, stands out for her poignant conceptualization, comparable in its interest with domestic material to the approach of conceptual art pioneer Rummana Hussain.

She calls us away from our homes to hers, whatever it becomes, to witness its stories of displacement from their own eyes, and know without a doubt whose hands turned the levers. It is politically charged, but layered in meticulous appeal that ensures it fits in nicely in exhibitions across Europe. Khan’s practice also contributes to a growing movement of diasporic South Asian artists who disrupt inherited histories, repurpose the material languages of femininity and craft, and teach us how to sit with discomfort, gently.

————————————————————–

Ebri Kowaki is a culture journalist and Afrofusion commentator. His works have appeared in The Republic, Afrocritik, African Writer Magazine, Akowdee Magazine, and elsewhere. A 2025 fellow of the Ebedi International Writers Residency, he was shortlisted for the Ikenga Prize in 2024.

ALSO READ TOP STORIES FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE