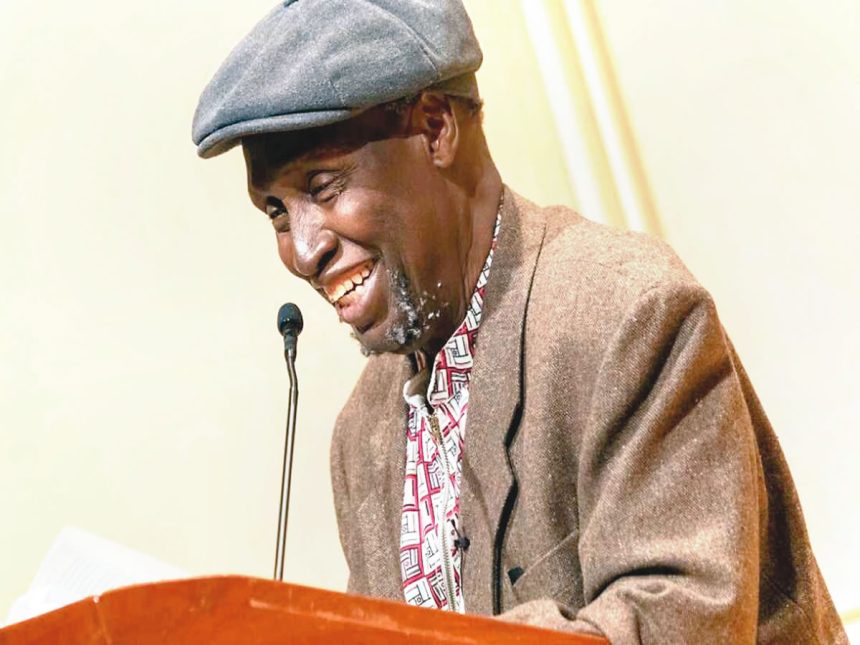

The iconic Kenyan author, scholar, essayist, and promoter of indigenous African languages leaves behind an imperishable body of work.

THE Yoruba proverb, “Bi oníresè bá kọ́ tí ó fìn igbá mọ́, ẹyí tó ti fìn ṣáájú kò leè parun” — If the master carver stops crafting exquisite calabashes, those he has already made remain indestructible — captures the enduring legacy of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The celebrated Kenyan author, scholar, essayist, and tireless advocate for indigenous African languages passed away on Wednesday, May 28, leaving behind a body of work that, as the proverb suggests, remains imperishable.

No matter how old our elders become, we rarely feel ready to let them go. People cry inconsolably at the loss of aged parents or relatives. It is no surprise, then, that Ngũgĩ’s passing has been met with deep, heartfelt mourning globally.

“It is with a heavy heart that we announce the passing of our dad, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, this Wednesday morning. He lived a full life, fought a good fight. As was his last wish, let’s celebrate his life and his work,” his daughter Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ posted on Facebook.

That simple but profoundly moving post was the final curtain on a rich, courageous, and extraordinary life that began on January 5, 1938, in Kenya. Born James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ in the Limuru district, one of his father’s 28 children by four wives, Ngugi came of age amid the tumult of the Mau Mau uprising. The brutal conflict involving his Kikuyu ethnic group and British colonial forces left an indelible mark on the young Ngugi. It sowed the seeds of protest that would later flourish in his writing.

He was educated at Kamandura, Manguu, and Kinyogori primary schools before Alliance High School, a British colonial institution in Kenya, and later at Makerere University in Uganda. His debut novel, ‘Weep Not, Child’, published in 1964 by the Heinemann African Writers Series, was the first English-language novel by an East African writer. Set against the backdrop of the Mau Mau rebellion, it announced the arrival of a bold new literary voice.

An expansive and fearless body of work — novels, short stories, plays and essays — then followed. ‘The River Between’, ‘A Grain of Wheat’, ‘Petals of Blood’, ‘Caitaani Mutharaba-Ini’ (Devil on the Cross), ‘The Black Hermit’, ‘The Trial of Dedan Kimathi’, ‘Ngaahika Ndeenda: Ithaako ria ngerekano’ (I Will Marry When I Want), ‘Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature’, ‘Mũrogi wa Kagogo’ (Wizard of the Crow), and ‘The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi’, among others.

An ideological and supremely confident writer, Ngugi fearlessly advocated for the use of African languages, even when his peers and others criticised him. From 1977, he wrote in Gikuyu before translating it into English.

“I have become a language warrior. I want to join all those others in the world who are fighting for marginalised languages. No language is ever marginal to the community that created it. Languages are like musical instruments. You don’t say, let there be a few global instruments, or let there be only one type of voice all singers can sing,” he told the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2017.

Ngugi’s fierce belief in self-worth and cultural pride resonates in his memoir, ‘Dreams in a Time of War’: “Belief in yourself is more important than endless worries about what others think of you. Value yourself, and others will value you. Validation is best that comes from within.” That message continues to inspire aspiring writers across the continent.

Spoken of in the same breath as literary icons Professors Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o leaves behind a multifaceted and unbreakable legacy.

Master artist Professor Bruce Onobrakpeya aptly captures this in a stirring tribute. He wrote: “Ngugi wa Thiong’o was more than a writer; he was a drumbeat, a voice carved from the very heart of our land. His words were like the colours I lay on canvas, rich with the pain and beauty of our people’s journey.

“Ngugi spoke in the language of the ancestors, reclaiming the forgotten tongues of our spirits. He wrestled with silence and exile, with chains designed to bind the mind, yet his spirit surged like a river—unyielding and fierce. To speak in one’s mother tongue is to hold a mirror to the soul; Ngugi held that mirror high, reflecting the dignity and defiance of generations.

“In the brushstrokes and etching lines of my art, I hear his stories. In the rhythms of his poetry, I see the dance of the masquerade—the sacred rites that link us to the past and the future. We are all keepers of memory; Ngugi wielded the pen as a spear, slicing through the veil of amnesia.

“His passing reminds us that art—whether in word or form—is a sacred fire. It burns through oppression; it illuminates the path home. As I remember Ngugi wa Thiong’o, honour the strength of a man who never bowed, whose legacy will continue to stir the hearts of those who dare to create, to speak, to remember.”

The writer, editor and critic Molara Wood also captured his loss and indelible legacy succinctly: “It is hard to put into words the immensity of this loss, the huge void left by the monumental figure of Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. They don’t come greater than this. He was one of the building blocks of the imaginative landscape of our lives, of the lives of generations of readers, especially in Africa. Long before the internet, before 24-hour news cycles, my first encounter with Kenya was on the pages of his books.

“In schools in the tiniest corners of Nigeria, pupils knew about Dedan Kimathi, the Mau Mau and the Kenyan struggle against British colonialism. They would feel for Njoroge, the protagonist of ‘Weep Not, Child’, as though he were their own cousin. It is really a towering testament to the power of literature, of the role of stories in our lives, and Ngugi Wa Thiong’o was a master storyteller whose visions will sustain us down the ages.”

Writer, journalist and scholar Dr Olayinka Oyegbile also acknowledged Ngugi’s influence on his generation, noting his role in decolonising their minds. Oyegbile said: “He showed us what it means to be Africans and how to think as one. He decolonised our minds. My first encounter with him was through ‘Weep Not, Child’. The book’s hero, Njoroge, still stands out in my mind. I read it as a youth, and now, in middle age, the image still stands there in my heart.

“When he decided to drop his first name, he explained why he decided to drop it and embrace his African name. His explanations made me drop my foreign name after I left secondary school as well. I am African, and through Ngugi’s works, he made me proud of my heritage.

“Many would perhaps rate him with his fiction. However, to me, he was like Chinua Achebe. His essays and nonfiction are more profound and richer. The nonfiction, among which are his three-volume autobiography ‘Writers in Politics’, ‘Decolonising the Mind’, and ‘Homecoming’ are everlasting.

Secretary General of the Pan African Writers Association, Dr Wale Okediran, acknowledged the deep vacuum Ngugi’s passing has left in African literature, especially his promotion of writing in indigenous African languages. In celebrating him, he disclosed that PAWA will soon institute a prize in his memory.

“By his family’s admonition that his passage should be celebrated, the Pan African Writers Association will soon announce a Literature Prize to be awarded to African Writers writing in Indigenous African Languages.”

READ ALSO: Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Nexus of a revolutionary African writer and Mbari writers’ club in Ibadan

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries