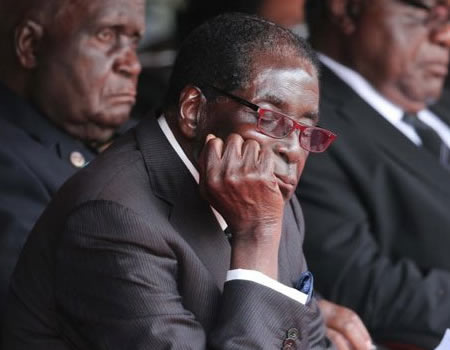

Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe was fired as leader of the ruling ZANU-PF party, according to senior officials at the party.

He was replaced by Emmerson Mnangagwa, the deputy he sacked this month, sources at a special ZANU-PF meeting to decide Mr Mugabe’s fate told Reuters.

“He has been expelled,” one of the delegates said.”Mnangagwa is our new leader.”

According to RTE report, Mr Mugabe’s wife Grace, who had harboured ambitions of succeeding Mr Mugabe, was also expelled from the party.

Speaking before the meeting, war veterans’ leader Chris Mutsvangwa said Mr Mugabe, 93, was running out of time to negotiate his departure and should leave the country while he could.

“He’s trying to bargain for a dignified exit,” he said.

Mr Mutsvangwa followed up with threat to call for street protests if Mr Mugabe refused to go, telling reporters: “We will bring back the crowds and they will do their business.”

Mr Mnangagwa, a former state security chief known as “The Crocodile,” is now in line to head an interim post-Mugabe unity government that will focus on rebuilding ties with the outside world and stabilising an economy in freefall.

Who are the key players in the Zimbabwe crisis?

Yesterday, hundreds of thousands of people flooded the streets of Harare, singing, dancing and hugging soldiers in an outpouring of elation at Mr Mugabe’s expected overthrow.

His stunning downfall in just four days is likely to send shockwaves across Africa, where a number of entrenched strongmen, from Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni to Democratic Republic of Congo’s Joseph Kabila, are facing mounting pressure to quit.

Men, women and children ran alongside the armoured cars and troops who stepped in this week to oust the man who has ruled since independence from Britain in 1980.

Under house arrest in his lavish ‘Blue Roof’ compound, Mr Mugabe has refused to stand down even as he has watched his support from party, security services and people evaporate in less than three days.

His nephew, Patrick Zhuwao, told Reuters Mugabe and his wife were “ready to die for what is correct” rather than step down in order to legitimise what he described as a coup.

But on Harare’s streets, few seemed to care about the legal niceties as they heralded a “second liberation” for the former British colony and spoke of their dreams for political and economic change after two decades of deepening repression and hardship.

The huge crowds in Harare have given a quasi-democratic veneer to the army’s intervention, backing its assertion that it is merely effecting a constitutional transfer of power, rather than a plain coup, which would entail a diplomatic backlash.