A month after the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) lifted the suspension of campaigns, majority of the political parties and their candidates for the 2023 general elections are still testing waters ostensibly slowed down by the huge logistics required to run a four-month electioneering across the country. WALE AKINSELURE examines the challenges of campaign funding vis-a-vis the mechanism to ensure compliance with relevant electoral Act.

In various discourses regarding on the challenges facing the country, lack of enabling laws is usually considered as a non-factor. Rather, lack of the political will to implement existing laws or the need to modify the laws to accommodate evolving realities are often identified as the main problem. Among others, an aspect of the nation’s democratic experience that Nigerians have yearned for improvement is enabling laws to improve the electoral process. The yearning is fuelled by the fact that the process has since the first one in 1922 been characterised by issues bordering on imposition of candidates, rigging, thuggery, stuffing of ballots, snatching of ballot boxes, falsification of election result, violence along with other electoral practices. New forms of electoral fraud and corruption have even evolved in the nation’s electoral process since re-emergence of democracy in 1999 with vote buying and massive monetization of politics as the burdensome challenges towards having a truly people-elected government emerging from an election. There are also the other factors undermining competitive electoral politics like “do-or-die” posture of some politicians, “winner-takes-all” philosophy, huge level of poverty and illiteracy, absence of clear ideological underpinning of the parties, religious bigotry, ethnic chauvinism, political corruption and delay in electoral justice.

Just after the 2019 general election, civil societies organisations noted that the election was characterised by violence, voter intimidation, ballot stealing, apathy, over militarisation, abuse of process by officials of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). Almost for every electoral cycle, laws are modified towards addressing the challenges and having an election where people’s sovereignty in choosing their leadership is not subverted. After the 2023 elections, stakeholders observed that the laws to do not effectively regulate the campaign expenditures of individual candidates contesting elections, though the laws require INEC to exercise control over political campaign expenditures. Section 225 (2) of the 1999 Constitution specifically requires the parties to disclose their sources of funds and manner of expenditures. However, stakeholders, then, observed that it may be difficult for INEC to fully monitor where parties and their candidates draw campaign funds from. Calls were then made on the commission to device ways and means of implementing the reporting, disclosure of all monies and assets received by the parties in aid of their campaign effort.

Even before independence, there were no clear laws regarding party finance and funding. The 1959 elections were conducted with no clearly defined regulatory framework on party finance and the funding of political parties was predominantly through private funding as parties and candidates were responsible for election expenses. During the Second Republic (1979-1983), it was a combination of private and public funding. Government, then, rendered financial assistance to parties by way of subventions. Private funding, except from outside Nigeria, was allowed, and there was no limit on how much corporate bodies and individuals could contribute to parties. The 1979 and 1983 elections were such that parties and politicians had unrestricted freedom to use money from both legal and illegal sources to finance their campaigns and other activities associated with their election expenses. Politicians attached much importance to money which they used to buy the votes of the electorates.

Nigerians have consistently expressed worries about party funding. According to the report of the Political Bureau on the national debate on the political future of Nigeria, Nigerians among other things expressed concerns about the administration and funding of political parties especially the seemingly freedom of limitations on political parties with respect to party funding during the 1979-1983 elections.

During an INEC-Civil Society Forum Society seminar on November, 27, 2003, former President Olusegun Obasanjo also pointed to the dangers associated with uncontrolled use of money for elections. Likening the cost expended on elections to that spent on war, Obasanjo said: “Even more worrisome, however, is the total absence of any controls on spending by candidates and parties towards elections. I have said that we prepare for elections as if we are going to war, and l can state without hesitation, drawing from my previous life, that the parties and candidates together spent during the last elections, more than would have been needed to fight a successful war. The will of the people cannot find expression and flourish in the face of so much money directed solely at achieving victory. Elective offices become mere commodities to be purchased by the highest bidder, and those who literally invest merely see it as an avenue to recoup and make profits. Politics becomes business, and the business of politics becomes merely to divert public funds from the crying needs of our people for real development in their lives.”

After the 2019 elections, top in the call of stakeholders is that the Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill passed by the National Assembly and declined by the President, should be re-introduced, passed by the National Assembly and transmitted to the president for assent. The yearn for amendment to the existing law was because, overtime, campaign funds do not only exceed the limit set by the electoral legal framework but also their sources and how they are utilized are not fully disclosed. The fact that the limit is mostly exceeded usually creates an uneven playing field, thereby reducing the chances of those who can’t afford the huge cost of campaigns. In fact, the financial requirements of campaign for political parties and candidates go higher election after election.

Provisions of Electoral Act

The parties seem to have turned a blind eye to provisions of the Electoral Act and the 1999 constitution (as amended).After much back and forth, President Muhammadu Buhari, on February 25, 2022, signed into law the Electoral Act Amendment Bill, 2022. Among others, section 85 of the law stipulates that: “Any political party that holds or possesses any fund outside Nigeria in contravention of section 225 (3) (a) of the Constitution, commits an offence and shall on conviction forfeit the funds or assets purchased with such funds to the Commission and in addition may be liable to a fine of at least N5,000,000. A political party shall not accept any monetary or other contribution which is more than N50,000,000 unless it can identify the source of the money or other contribution to the Commission.”

In setting election limits, section 88 of the Electoral amendment law stipulates that the maximum election expenses to be incurred by a candidate at a presidential election shall not exceed N5billion; N1billion for governorship election; N100 million for Senatorial election and N70million for House of Representatives contest. For State Assembly election, the maximum amount of election expenses to be incurred by a candidate should not exceed N30, 000,000 same as chairmanship election to an Area Council while in the case of Councillorship election to an Area Council, the maximum amount of election expenses to be incurred by a candidate should not exceed N5, 000,000.

ALSO READ FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE

Furthermore, the law also sets a N50million limit to any individual or other entity that wants to donate to a candidate.“A candidate who knowingly acts in contravenes is liable on conviction to a fine of one percent of the amount permitted as the limit of campaign expenditure under this Actor imprisonment for a term not more than 12 months or both,” the law states. The law adds: “Election expenses incurred by a political party for the management or the conduct of an election shall be determined by the Commission in consultation with the political parties. Election expenses of a political party shall be submitted to the Commission in a separate audited return within six months after the election and such return shall be signed by the political party’s auditors and countersigned by the Chairman of the party and be supported by a sworn affidavit by the signatories as to the correctness of its contents. A political party which contravenes subsection (3) commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a maximum fine of N1,000,000 and in the case of failure to submit an accurate audited return within the stipulated period, the court may impose a maximum penalty of N200,000.00 per day on any party for the period after the return was due until it is submitted to the Commission.

“Any political party that incurs election expenses beyond the limit set in subsection (2) commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a maximum fine of N1,000,000 and forfeiture to the Commission, of the amount by which the expenses exceed the limit set by the Commission.”

Past records

Upon the president’s assent to the electoral act amendment law 2022, stakeholders pushing for regulations to party funding hold that such regulation will help control fraud and political finance related corruption, promote active and efficient political parties and ensure openness and transparency in the electoral process. However, several stakeholders wonder whether the limits set in the electoral law will actually limit outrageous spending by the big political parties. With campaigns by political parties kicking off, stakeholders also wonder what mechanism will monitor when the parties and candidates beat the campaign spending limits. Findings after elections consistently show that political parties also do not comply with the requirement for submission of their financial reports to INEC. A report showed that as against the N1billion campaign spending limit for the 2015 election, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) spent N8.74 billion while the All Progressives Congress (APC) spent about N2.91 billion.

The parties already set the tone for huge spending for the 2023 elections with the All Progressives Congress (APC) announcing N100million as cost of expression of interest and nomination forms to be its presidential standard-bearer while the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) set its own at N40 million.

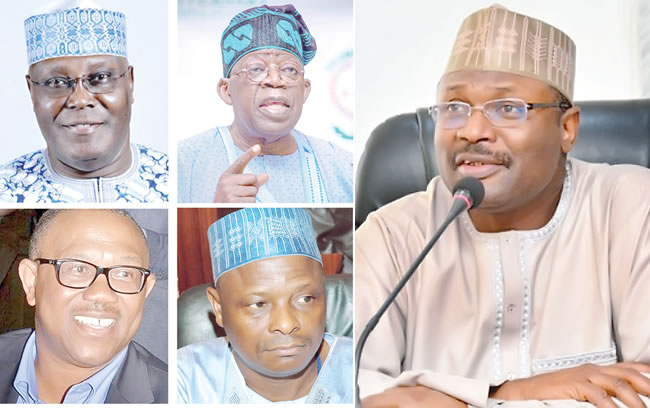

At a review of the last general elections with political parties in July 2019, INEC’s Chairman, Mahmood Yakubu, disclosed that “only one presidential candidate has submitted a financial expenses report,” three months after the election. There is also the argument that the penalties for flouting the electoral guidelines are too small and not strong enough to serve as a deterrent.Indeed, the 2023 campaign will be the extent to which Senator Bola Tinubu and the All Progressives Congress (APC) can outspend the duo of Alhaji Atiku Abubakar and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP); and Mr Peter Obi and the Labour Party (LP).

What can be done

While questions continue to be raised about the source of the multi-billion naira campaign funding of Tinubu and Atiku, Peter Obi of the Labour Party in a bid to raise the sum of $150 million in the Diaspora and N100 billion in Nigeria was reported to have embarked on a tour of Canada and Germany and seven cities in the US, with the aim of raising this campaign fund. Similarly, the candidate of the African Action Congress (AAC), Omoyele Sowore is said to be banking on crowd funding from Nigerians and aid from foreign agencies to sustain his campaign financing. But, the dilemmas both Obi and Sowore would face is, first, that Nigerian laws forbid foreign donations for electoral campaigns in the country.

Worried about the sources of campaign funding, renowned columnist, Dr Festus Adedayo tasked Nigerians to ask their candidates specific questions about how they will finance the elections and the specifics of accountability in campaign financing. Adedayo said: “In developed democracies, a track-able account is opened and a certified accountant is put in charge of the campaign office account. Every penny, whether secured through crowd funding, public or private donations, so far it goes into this account, is periodically subjected to the scrutiny of auditing. Not doing this same thing with our candidates and political parties vying for offices in 2023 is akin to opening doors of Nigeria’s decision-making offices to the god of Mammon. It will also amount to a triumph of the whims of evil forces in society.”

Similarly, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) sent an open letter to presidential candidates ahead of the February 2023 election, urging them to demonstrate leadership by directing their “campaign councils and political parties to regularly and widely publish the sources of their campaign funding. ”Through its deputy director, KolawoleOluwadare, the organisation said: “If Nigerians know where the money is coming from, they can scrutinise the details, and hold to account the candidate and party that receive it. Transparency in campaign funding would ensure fair and open elections, and address concerns about undue influence by the more economically advantaged and privileged individuals, as well as prevent corruption of the electoral process. Political parties provide the necessary link between voters and government. No other context is as important to democracy as elections to public office. Nigerians therefore must be informed about the sources of campaign funding of those who seek their votes.”

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries