Peter Wafula Wekesa

Kenya has this year lost two of its eminent intellectual powerhouses to the ancestral world. The death of Prof B.A. Ogot and Prof. Ngugi wa Thiongó, in January and May, respectively, presented the country with a moment of collective grief not just for the loss of these great men of the literary and historical worlds, but also in the shared sorrow of the void left by their loss. Both Ogot and Ngugi represented a crop of pioneer scholars who put the country and continent on the global map.

While they were both pioneers in the global scholarly community, they were first and foremost members of the pioneering African intellectual family. It is for this reason that their passing provided an opportunity both to mourn and celebrate, especially among the scholarly community that imbibed their massive contributions to knowledge. These great men had consumed books with a voracious appetite, and in turn nourished generations with the great gift of their intellectual power.

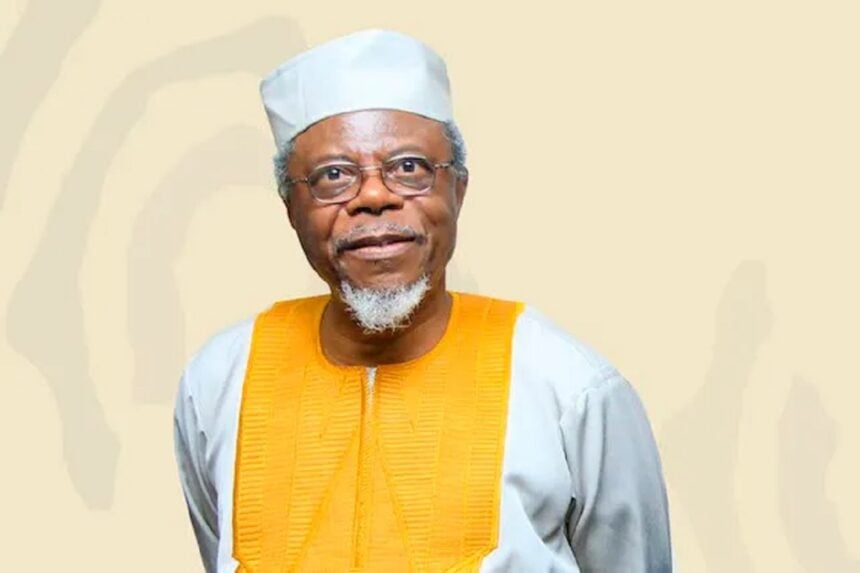

When both Prof. Ogot and Ngugi passed away, it was Prof. Toyin Falola who spearheaded the solemn celebration of their passing through the now-famous Toyin Falola (TF) Interviews. The TF interviews, a public digital forum and video series that spotlights in-depth conversations with prominent African intellectuals, leaders, artists, and scholars, have evolved into a continental and global voice on key issues in African history, decolonization, culture, and future developments.

Led by Prof Falola, a Nigerian born but US based historian of great stature, the TF interviews on Ogot and Ngugi brought together senior academics and Professors in the field of history and literature who had interacted closely with the departed doyens, and with their works to reflect on their contributions on the African knowledge economy.

In a way, this forum innovatively created a space through which the intellectual community reconnected with the souls of the departed senior colleagues, and at the same time, provided a space to rethink the primacy of intellectual power in the transformation of the social, economic, and political contexts in which we live. One could say that Prof Falola’s initiative was simply an expression through which scholars mourn their kin, through the power of the pen. However, the seizing of virtual spaces as platforms for sharing experiences is opening new opportunities for collaborations in teaching, research, and community outreach beyond the traditional known modes.

Professor Falola’s planned visit to Kenya, between July 12 and 20, 2025, signals a moment of transition and reflection in many ways. The first and immediate one is that he is, symbolically speaking, bringing both Ogot and Ngugi back home. From the virtual TF interviews, Kenyan students and scholars will have the privilege of a physical encounter with a highly esteemed historian and academic who is widely recognized as a leading voice in African Studies today.

Falola’s eminence is not just in the fact that he has published over 150 books and received well over 30 lifetime awards, but by the mere fact that he is a down-to-earth, humorous, and generous scholar. Like Ogot and Ngugi, Falola’s unmistakable imprint on scholarship, teaching, and leadership has had a transformative impact on how African and African culture are taught and understood worldwide. His previous visits to Nairobi left indelible marks in the minds of men and women who took time to listen and interrogate his deep defense of African knowledge systems.

Prof. Falola has on many occasions challenged the overbearing impacts of Western knowledge systems on the African academy. As a staunch defender of African knowledge systems, he has consistently cautioned African scholars to be aware of the various colonial knowledge regimes that have seeped through the African continent’s character, beliefs, and structures over time.

It is no coincidence that Prof. Falola’s visit, and the three public lectures lined up at the British Institute of Eastern Africa, the University of Nairobi, and Kenyatta University, will focus on the question of power. This is his pet subject, whose timely reflection will deeply resonate with the current developments in Kenya and Africa as a whole.

It is worth recalling that Falola is one of the few scholars who have boldly confronted and extensively written about the nature, structures, and dynamics of power in Africa, particularly from the pre-colonial to the postcolonial era.

His views on power are rooted in a deep historical understanding and an Afrocentric critique of both internal and external forces that have shaped African societies. Since knowledge operates within specific social, economic, and political power contexts, scholars must critique Eurocentric epistemologies that continue to allow Africans to discard many of their beneficial models and approaches in favor of Euro-American ones. The latter borrowed systems, according to Falola, are not adaptable to the African condition and continue to consign socio-economic and political developments in Africa to insubordinate levels. As purveyors of intellectual power, African scholars must therefore be steadfast in ‘intellectualizing power using indigenous philosophical frameworks and stop imitating hegemonic templates.

The contextual timing of Falola’s lectures on power is not to be missed. Any attempt to intellectualize power within the current African context must take into account several historical considerations. First, there is the realization that power in Africa is not a postcolonial invention, but a long-standing historical reality shaped by indigenous institutions, spiritual authority, kinship systems, and political hierarchies. Secondly, there is the appreciation that colonial rule, in very significant ways, undermined traditional authority structures and replaced them with foreign, often exploitative governance models.

Thirdly, there is the awareness that at independence, instead of the African leaders deconstructing colonial legacies, many countries resorted to constructing postcolonial regimes that centralized power, suppressed dissent, and entrenched authoritarianism.

Lastly, it is to understand that given the overbearing presence of the authoritarian state, ordinary citizens are increasingly resisting power and creating avenues that redefine and reconnect with their daily experiences and interests. These are weighty issues that scholars must confront, and which Falola’s Kenyan lectures will seek to address.

As we are aware, the Kenyan state is currently at a crossroads. Many questions are being raised about the country’s political direction. The government is quickly losing its grip as a regional economic and political powerhouse, and as a beacon for peace and relative stability in East Africa. A country that has historically been celebrated for giving the world symbols of resistance and independence through the Mau Mau war of liberation is slowly becoming a shadow of its former self. We no longer talk about the two most significant contributions of the country to Africa and the world in the 21st century: the birthplace of coalition politics and the power-sharing model, and the momentous Gen Z revolution.

All these are because of power. The failure by the political class to establish democratic institutions and redistribute power equitably has led to widespread corruption, marginalization, and internal conflict. The hope that many Kenyans had at independence is quickly being replaced by misery and despair, a condition that is spiraling into the prevailing state of near anarchy. In the meantime, the state, like its colonial progeny, has become a tool of impunity, control, and economic extraction, thus disempowering many at the expense of a few kleptocrats.

Prof. Falola’s lectures on power wouldn’t have come at a better time. The months of June and July of every year are historic in Kenya’s popular struggles and entanglements with power. From the July 7, 1990, events dubbed Saba Saba (Seven Seven) that ushered in the multiparty system of government to the June 24, 2024, Gen Z protests that led to the invasion of parliament, the protest spirit has been kept alive, especially among the young generation. We now have a generation of Gen Zs who are leaderless, partyless, fearless, and tribeless, who have reignited the spirit of resistance and protest, and who consequently have pushed the real essence of revolutions to new, significant levels.

This is the group that holds the key to Africa’s future transformation. This is the group that will primarily gather to listen to Professor Falola as he provides them with the intellectual tools to understand and confront their current circumstances. Scholars must intellectualize state power by asking hard questions. These complex questions, according to Falola, include who the state serves and what intellectual perspective it houses. These are not easy questions, but are questions whose answers are urgently needed. To do so, it’s crucial to gain a deeper understanding of our historical circumstances and make deliberate efforts to understand, restore, and shape our collective destinies.

We need to be bold enough in historicizing our experiences and ensuring that our intellectual spaces emphasize the news of Africa’s achievements in social, economic, political, and technological spheres that had previously been ignored in the Eurocentric knowledge systems. There is thus an urgent need to cultivate a social and academic landscape that favors the African narrative as the most effective way to exert influence over our people. “Power is not a trophy to be won, but a trust to be held,” affirmed Toyin Falola.

Karibu Kenya, Professor Falola.

ALSO READ TOP STORIES FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Relationship Hangout: Public vs Private Proposals – Which Truly Wins in Love?

- “No” Is a Complete Sentence: Why You Should Stop Feeling Guilty

- Relationship Hangout: Friendship Talk 2025 – How to Be a Good Friend & Big Questions on Friendship

- Police Overpower Armed Robbers in Ibadan After Fierce Struggle