Nearly two decades after Nigeria’s last population census, the country continues to govern and plan using estimates from foreign bodies. PHILIP IBITOYE examines Nigeria’s troubled history of census-taking and how outdated data undermines national development plans and revenue-sharing reforms.

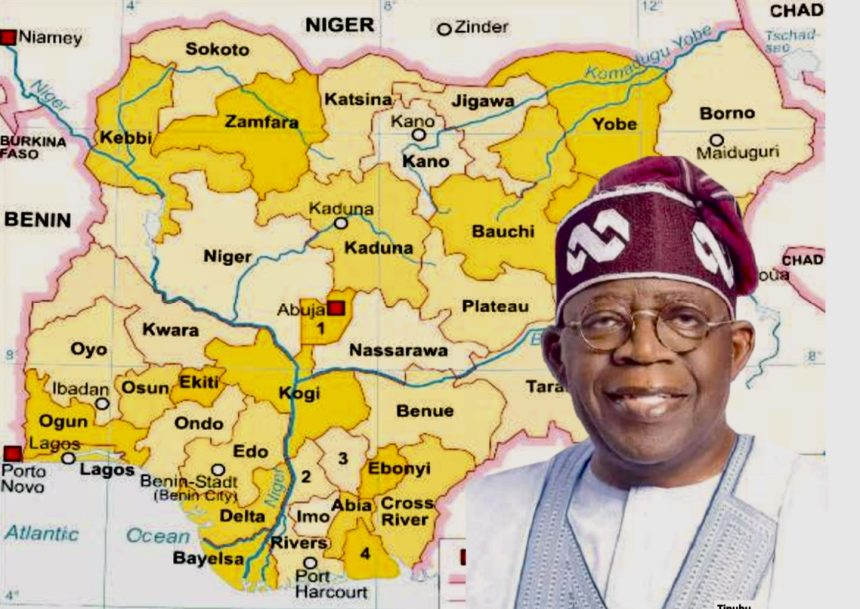

When President Bola Tinubu inaugurated a committee in April 2025 to lay the groundwork for a long-delayed national population and housing census, many saw a glimmer of hope that Nigeria might finally break its near 20-year census drought. The President gave the committee, chaired by Budget and National Planning Minister Atiku Bagudu, three weeks to submit an interim report. But four months later, the last public update from the ministry remains the committee’s April 25 meeting, and no firm timeline for the census has emerged. The last census held in 2006 and another one ought to have been conducted ten years later, in 2016.

The continued delay in conducting one leaves Nigeria in a dangerous limbo, according to economic and political analysts who spoke with Sunday Tribune. The country continues to make policy, allocate resources, and even calculate its poverty rate using population estimates — mostly projections by the United Nations (UN), World Bank, and other foreign agencies — rather than verifiable, home-grown data. For a country of Nigeria’s size and complexity, the implications are seen as political as much as they are economic.

A 2025 Policy Paper on National Identification, Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems, entitled “Can the Government See You?” and published by BudgIT, noted that Nigerian citizens aged 18 years or younger have never experienced a proper census exercise. The implication, the paper states, is that government at all levels from federal to state and local has operated on assumptions or guesswork. “Governments need vast amounts of legitimate and high-fidelity information (on their workforce) and the people over whom they superintend,” the research paper reads in part.

But Nigeria’s struggle with census is not new. When the process has not been delayed in the past, it has been discredited and rejected by sections of the country who believed it to be flawed.

A turbulent history of headcounts

The turbulent history of census-taking dates back to the colonial era. The first nationwide attempt in 1952–53 recorded a population of around 31 million, but coverage was seen to be uneven. The disruption of the Second World War was said to have made people suspicious of the intention of the exercise, causing them to refuse to submit themselves for counting.

The post-independence censuses of 1962 and 1963 were mired in accusations of inflation and manipulation, as rival regions saw population figures as a ticket to political dominance and a greater share of federal revenue. The government refused to accept the results of the 1962 census due to alleged politicisation, prompting the 1963 census.

The 1963 census, which put Nigeria’s population at 55.6 million, was also hotly contested and contributed to the political instability that preceded the January 1966 coup. These contestations did not happen in a vacuum, according to public analysts, who argue that census in Nigeria has always carried an ethno-religious undertone. Since population figures determine representation in the House of Representatives, the distribution of local government areas, and federal character quotas in the civil service, military, and public universities, every headcount becomes a proxy battle for power and legitimacy.

Fears of undercounting one group or inflating another have repeatedly turned census exercises into high-stakes contests. Religious groups have not been exempt. Some Christian and Muslim leaders have historically mobilised their followers to participate or boycott censuses depending on perceptions of bias. The result is a vicious cycle: mistrust leads to poor participation, which leads to flawed results, which further entrenches mistrust.

The next census after the 1963 census held between November 25 and December 2, 1973, but it was also widely discredited and went unpublished on the grounds of deliberate falsification of the population figures for political and ethnic benefit. However, the next censuses in 1991 and 2006 were more broadly accepted and praised for improvements in methodology because they were scientific. Yet they still attracted criticism over credibility and politicisation. For example, the 2006 census allegedly witnessed inflation of figures in parts of the country.

In an interview with Sunday Tribune, the Global Director of Brain Builders Youth Development Initiative (BBYI), Abideen Opeyemi Olasupo, said the 2006 exercise featured some people inflating the number of people in their families. “I still have issues with the last population census. We had a person who had not given birth during the census saying he had married three wives and given birth to 20 children,” he said.

Hence, the result of previous censuses has been a persistent mistrust of official numbers, with every region convinced it has either been short-changed or undercounted. But some observers worried about the lack of a census in the last 19 years argue that a census is still mandatory to ensure adequate economic and development plans.

Lack of credible population data likely contributing to failure of national development plans, budgets

From 1962 to 1985, dubbed the era of fixed-term planning, Nigeria operated a system of four-year National Development Plans — ambitious blueprints for infrastructure, education, and industrial growth. Population data was the backbone of these plans, determining where schools, hospitals, and roads were built. But when census figures were disputed or outdated, the plans faltered. Projects were misallocated, some areas became over-served while others were neglected, and resources were spread too thinly. The failure of those plans, culminating in the structural adjustment era of the mid-1980s, is said to be partly a failure of data.

More recent plans, such as the 2017–2020 Economic Recovery & Growth Plan and the 2021–2025 National Development Plan (NDP), have faltered and failed to attain various benchmarks due to their use of estimated population numbers that do not reflect reality. For example, the 2021–2025 NDP promised to lift 35 million people out of poverty and create 21 million full-time jobs, but there is no evidence that the federal government has achieved even a fraction of these lofty ambitions.

Last week, Bagudu said the National Economic Council (NEC), led by Vice-President Kashim Shettima, has approved a new NDP for 2026–2030, which will replace the largely unsuccessful 2021–2025 plan. The economic planning minister acknowledged that the 2021–2025 plan could not achieve the projected 7% growth due to the absence of strong political will to implement necessary reforms for its success, but economic experts believe outdated population data contributed to its failure. Accordingly, the 2026–2030 plan and other plans such as the Nigeria Agenda 2050 (NA-2050), launched in 2023 by former President Muhammadu Buhari and aimed at propelling Nigeria into the league of upper-middle-income and high-income economies by 2050, may fail like their predecessors without credible population data.

Also, as the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC) reviews the revenue allocation formula for the first time in 33 years, concerns are mounting over the impact a lack of recent population data may have on the exercise. Although it is not clear how much weight population has in determining the allocation of revenue to various states and local governments, it is one of the factors in the current formula for determining allocation. Without a current census, any review risks perpetuating old inequities. States with significant population growth over the past two decades may still be treated as though they have smaller populations, while those with slower growth may retain a disproportionately high share of resources.

Speaking on the importance of population data to economic planning and responsible allocation of resources, the Group Head of Research at BudgIT, Vahyala Kwaga, said accurate population data is more than just critical: it is indispensable to responsible economic planning.

“If the understanding that the government exists to serve the people is true, then having precise data on those citizens is an imperative. Accurate citizen data is also significant in helping determine the adequate level and range of resources needed. Where the number of citizens is known with specificity, it aids in deploying resources and helps save what would otherwise be spent frivolously. Exact data is key also for planning, as it ensures that demographic trends can be projected with greater perfection,” Kwaga told Sunday Tribune.

The BudgIT head researcher also argued that the continued lack of recent population data negatively distorts budget allocations for health, education, and infrastructure because it means resources are not targeted.

He added: “When allocating funds for social services and infrastructure, a relatively precise number is salient as lives [and their continued survival] are at stake. Where the data is imprecise, the existence of those lives will hang in the balance and not be taken seriously. [Having near-accurate population data] will ensure that the pace of expansion of government health and education infrastructure and personnel will match population dynamics.

“It will also ensure that the pace of expansion of hard infrastructure (roads, bridges, railways, ports, power lines and communications lines) by the government and the private sector follows the dynamism of populations and does not play ‘catch-up’.”

Similarly, the BBYDI global director said the lack of census in nearly two decades has undermined evidence-based planning for infrastructure, healthcare, education, and security. “It even distorts revenue allocation between state and local government,” he added.

Lack of census leads to unfair political representation — Analysts

The absence of a credible census also affects political representation, according to political analysts. Nigeria’s electoral constituencies are meant to reflect population size, but the last delimitation exercise relied on 2006 figures. Some states have likely seen explosive growth, but their number of constituencies has not been adjusted accordingly. This means millions of Nigerians are likely underrepresented in parliament, skewing the democratic process.

Political analyst Afolabi Olawale noted that if the government does not conduct a census, there would be no knowledge of population growth in a state and the need to allocate resources and representation to it accordingly. “[The continued delay in conducting a census] definitely affects representation because while certain areas might need more persons to represent them due to the increase in population, this would not happen simply because the government is not even aware of the increase in their population,” he said.

Olasupo also stated that without credible census data, there are likely many electoral boundaries and constituencies being misaligned with actual population size and distribution. “This situation creates inequities where some areas are overrepresented while others are underrepresented in the National Assembly or maybe perhaps the states’ legislatures. It even undermines the principle of one person, one vote and compromises legitimacy of democratic institutions,” he said.

However, observers blame the delay and lack of urgency in conducting a census on the lack of political will of relevant leaders.

According to Olawale, population has been a political tool since independence due to its relevance in the allocation of revenue and political representation. “Every politician trying to outsmart one another tries to avoid it [census], especially if it would go against them. So is it deliberate [that no census has been conducted in 19 years]? Yes, largely because you wouldn’t say conducting census once in ten years would kill the country if there is proper planning,” the political analyst said.

Likewise, the BBYDI global director said there are strong incentives for political leaders to manipulate the census exercise because population data directly affects federal revenue sharing and political representation. “It [population data] also affects the perception of regional dominance. So, leaders in this region or state who fear being shown to have fewer numbers may resist a credible count, while others may prefer it because it allows them to exaggerate the claims of ‘we have one million persons in this local government’ and it also allows them to maintain political leverage. So, in Nigeria, if you look at it deeply, it’s tied to competition for power and resources.”

A national priority waiting to happen

Meanwhile, civil society groups have urged the federal government to treat the census as a matter of national security, arguing that accurate population data is essential for managing food security, public health, urban planning, and counter-insurgency operations. They argue that a credible, transparent census would update the country’s statistics, restore public trust, rebalance political representation, and improve the efficiency of public spending.

But to succeed, the exercise must be insulated from the ethno-religious and political pressures that have dogged previous attempts. That means robust technology, transparent methodology, independent oversight, and strong public buy-in, according to Olasupo.

“There should be a clear law insulating census administration from executive or partisan control. We should prioritise technology, including biometric and geospatial tools, to reduce human manipulation,” he said.

“Then there should be independent oversight from multi-stakeholder monitoring bodies comprising civil society organisations, religious and traditional leaders. There should also be conflict-sensitive planning, which involves early dialogue in communities with histories of senseless violence or disputes. There is also the public communication aspect, which requires transparent, real-time updates to prevent rumour-mongering and suspicion.”

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries