The exhibition traces the evolution of modern art in Nigeria across generations, showcasing works from the period of indirect colonial rule through independence and into the present.

ENTHUSIASTS, aesthetes, and connoisseurs of Nigerian visual arts will have a rare chance to view works by 50 eminent artists from different generations, beginning October 8, 2025, when ‘Nigerian Modernism’ opens at the Tate Modern, Bankside, London, United Kingdom.

Curated by Tate Modern’s International Art curator, Osei Bonsu, and his assistant, Bilal Akkouche, ‘Nigerian Modernism’ is a significant exhibition tracing the development of modern art in Nigeria.

The United Kingdom’s first exhibition appraising the history of Nigerian modern art will showcase artists and works from the era of indirect colonial rule to independence and the present.

Open daily from 10 am to 6 pm until May 11, 2026, the exhibition will celebrate an international network of artists who combined African and European traditions, creating a vibrant artistic legacy that continues to captivate audiences globally.

Organised by Tate Modern in partnership with Access Holdings and the Coronation Group, ‘Nigerian Modernism’ will feature over 250 works, including paintings, sculptures, textiles, ceramics, and works on paper from institutions and private collections across Africa, Europe, and the US.

A detailed statement from the Tate Modern on the show, also supported by Ford Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Nigerian Modernism Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Americas Foundation, says it offers a rare opportunity to encounter the creative forces who revolutionised modern art in Nigeria.

The Tate Modern disclosed that the exhibition starts in the 1940s, “amid calls for decolonisation across Africa and its diaspora. With the Nigerian education system under British governance, many artists trained in Britain adopted European artistic techniques and styles. They witnessed Western modernism’s fixation on African art. The balance between Nigeria’s indigenous traditions, colonial realities and calls for independence was evident in the practices of artists, many of whom became involved in arts education and reform.”

It added that “Aina Onabolu pioneered new figurative portraits of Lagos society figures, whilst Akinola Lasekan depicted scenes from Yoruba legends and history. Globally celebrated artists of the period, Ben Enwonwu and Ladi Kwali, combined their Western training with Nigerian visual art traditions. Drawing upon his knowledge of Igbo sculpture, Enwonwu adapted his Slade School education to celebrate the beauty of Black and African culture. Meanwhile, Kwali, who trained under British potter Michael Cardew at Pottery Training Centre in Abuja, developed a new style of ceramic art that synthesised traditional Gwarri techniques and European studio pottery.”

The statement continued: “National independence on October 1, 1960, inspired a sense of optimism throughout the country, with artistic groups creating art for a new nation. The exhibition will examine the legacy of the Zaria Arts Society, whose members included Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Yusuf Grillo, Bruce Onobrakpeya, andJimo Akolo. Encouraged by teachers like Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, they developed independent, creative styles centred around the concept of ‘Natural Synthesis,’ merging indigenous forms with modern expression.

“In the 1960s amid an economic boom, Lagos became a dynamic cultural hub, inspiring tropical modernist architecture, public art commissions and nightclubs filled with Highlife music. Meanwhile, in Ibadan, the Mbari Artists’ and Writers’ Club, founded by German publisher Ulli Beier, offered a discursive space run by an international group of artists, writers and dramatists including Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Malangatana Ngwenya. The Mbari Club was closely associated with the influential Pan-African modernist journal Black Orpheus, which will be displayed at Tate Modern.

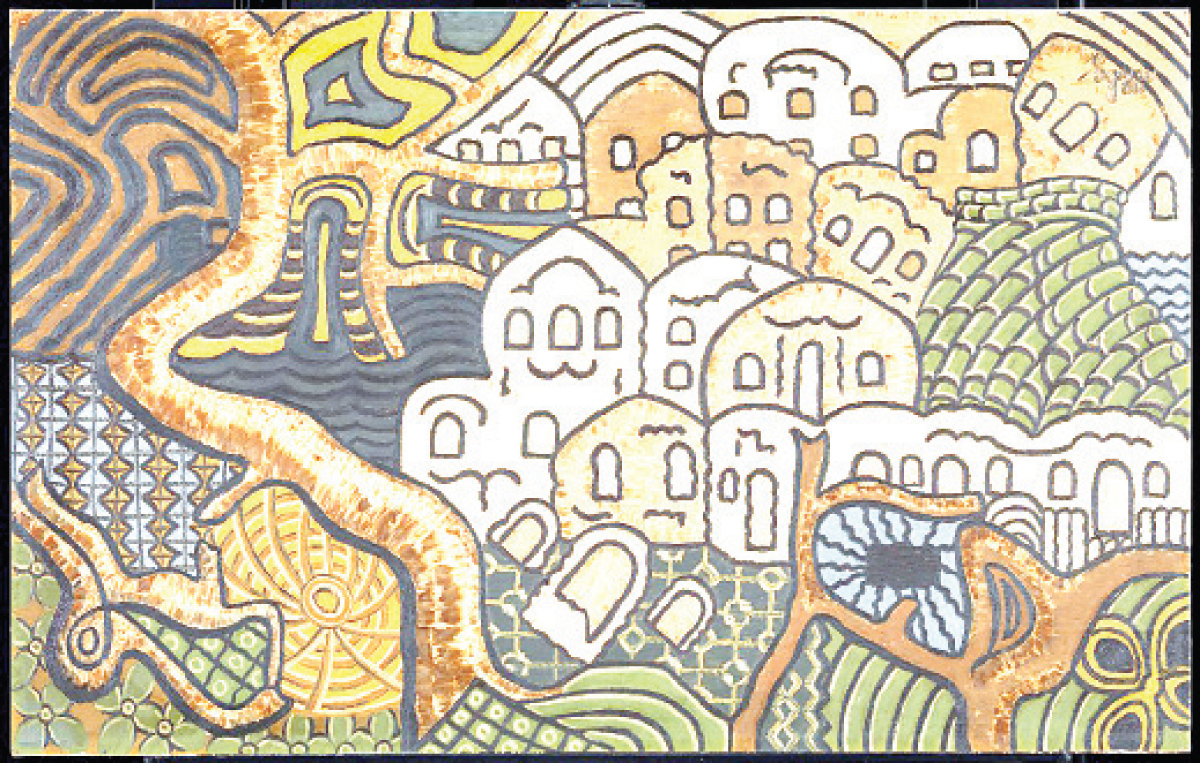

“During this period, many artists reflected on Nigeria’s rich cultural and religious heritage as home to more than 250 ethnic groups. The late 1950s saw the emergence of the New Sacred Art Movement, founded by Austrian-born artist Susanne Wenger, who drew on Yoruba deities and beliefs to explore the ritual power of art. The group led the restoration of the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, where ancient shrines were adorned with cement sculptures and carvings. In parallel, the Osogbo Art School emerged from a series of influential workshops at Duro Ladipo’s popular bar, providing a space for experimentation among untrained artists and performers, including Nike Davies-Okundaye, Jacob Afolabi, and Twins Seven Seven, who explored Yoruba cultural identity and personal mythologies in their work.

“The outbreak of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967 caused a cultural and political crisis for many artists. The post-independence feeling of optimism and unity was replaced with division, and later a desire to reconnect across Nigeria’s diverse ethnic groups. The exhibition will focus on the revival of ‘uli’ – linear Igbo designs that can be decorative or represent natural elements and everyday objects. Historically passed down between women, artists like Uche Okeke, who had inherited this knowledge from his mother, and those from the Nsukka Art School, including Obiora Udechukwu, Tayo Adenaike and Ndidi Dike, adapted this visual language as a modernist art form, reclaiming an element of ancestral culture and reflecting on the struggles of conflict during the Nigerian Civil War.

“The exhibition will end with a spotlight on Uzo Egonu, exploring how artists towards the end of the 20th century began to respond to global Nigerian identities.”

Commenting on the collaboration, Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede, Chair of Access Holdings and Coronation Group and a member of Tate’s International Council, said: “This exhibition speaks to our responsibility to protect, promote, and celebrate Africa’s cultural wealth. Our partnership with Tate reflects our commitment to democratise access to culture and inspire the next generation of African creatives.”

A country of supremely talented artists, ‘Nigerian Modernism’ couldn’t be happening at a better time, when interest in pioneering artists and their works is being rekindled locally. Among other efforts by private individuals and organisations, journalist and politician Babafemi Ojudu is leading an initiative to document the works of Olowe of Ise, some 87 years after his passing.

In London, at Tate Modern, that spirit of rediscovery comes vividly to life.

ALSO READ TOP STORIES FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries