Dr Desmond Rowland Eteh is a geoscientist and environmental expert based in Port Harcourt. He is a data scientist and geospatial analyst with Golden Viosam Limited. In this interview with Kingsley Alumona, he speaks about his work with artificial intelligence (AI) and big data, and how such technologies can benefit Nigeria.

You studied Geology and Geophysics up to the PhD level. But you are currently into tech, especially artificial intelligence (AI) and data science. What inspired your love for tech?

My tech journey was catalysed by the inherent limitations of traditional geoscience during my PhD research. While studying flood risk assessment in the Niger Delta, I encountered recurring challenges: conventional methods like manual soil sampling and static GIS models couldn’t predict rapid hydrological changes. For instance, during the 2021 flood season, traditional models failed to account for real-time rainfall variability, leading to delayed evacuations. This gap drove me to explore machine learning (ML) and remote sensing.

The fusion of geoscience with tech not only enhanced accuracy but also underscored the transformative potential of AI in solving environmental crises. This interdisciplinary approach became my passion, bridging geoscience’s theoretical depth with tech’s scalability.

How do you apply your data science and geospatial expertise to solving climate and environmental problems in Nigeria?

I combine geospatial analytics (e.g., Sentinel-1 SAR data) with machine learning to tackle issues like flooding, greenhouse gas, oil spills, and waste management. For instance, my flood prediction models use satellite imagery and rainfall patterns to guide early warning systems. I’ve also mapped illegal dumpsites using multispectral imagery and ground data, helping policymakers prioritise cleanup efforts in high-risk zones like the Niger Delta.

Apart from climate change and environmental issues, which other areas or sectors do you apply your AI and data analysis skills?

Beyond environmental work, I apply AI in oil and gas (e.g., optimising spill detection with SAR data) and urban planning. My air quality prediction model aids public health planning, while geospatial workflows support infrastructure projects, such as assessing soil stability for construction. These cross-sector applications show how AI can drive efficiency and safety in resource management and development.

Climate change, to some extent, affects Nigerian weather patterns and ecosystems. How could AI and data science be used to understand these problems and proffer solutions to them?

AI processes vast datasets (e.g., satellite imagery and weather sensors) to identify patterns invisible to traditional analysis. For Nigeria, this means predicting flood-prone areas, tracking coastal erosion, or correlating gas flaring with rainfall changes. My work with Sentinel-1 data and XGBoost models, for example, quantifies flood risks in real-time, enabling proactive disaster response and climate adaptation strategies.

For example, in the Niger Delta area where I’ve worked and published some articles, I developed an AI model to detect oil spills, reducing false positives by 40 percent. This helps regulators hold polluters accountable. Another of my project in the Niger Delta used machine learning to correlate gas flaring sites with air quality declines, informing stricter enforcement of emission laws in Bayelsa State.

Can you share a machine learning project where your work directly helped solve an environmental problem?

One key project was my flood prediction system for the Niger Delta. By training an ensemble model on historical flood data, Sentinel-1 imagery, and geoelectric measurements, accuracy improved by 30 percent. This system is now used by local agencies to allocate resources during rainy seasons, reducing evacuation delays, and property damage.

What risks should developing countries like Nigeria consider when using AI for climate action?

Key risks include biased datasets (e.g., urban-centric models failing rural areas), over-reliance on tech without local input, and infrastructure gaps (e.g., poor internet). To mitigate this, I involve communities in data collection and validate models with ground-truth data. Ethical AI must prioritise inclusivity and adaptability to local contexts.

What is your advice to the government on the use of AI and big data in managing pressing problems, especially environmental problems, in the country?

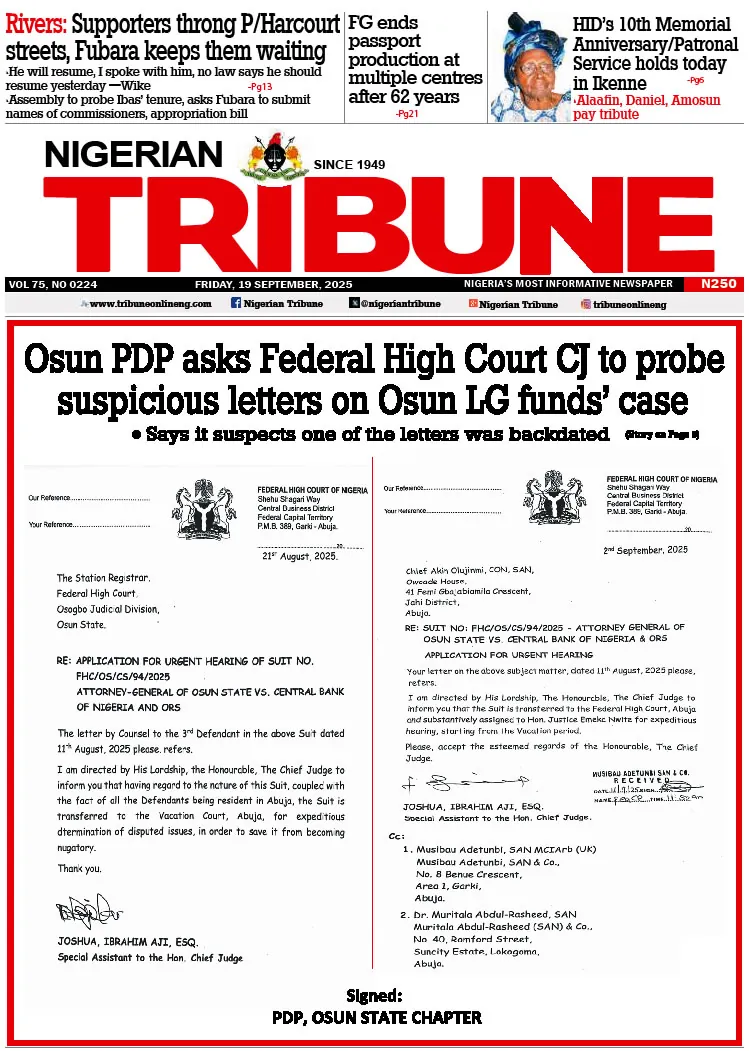

Some of the advice I will proffer here is available in some of my recently published works in the Guardian titled ‘How govt can leverage AI to address environmental challenges—Dr. Eteh’; Nigerian Tribune newspaper titled ‘Utilising digital technologies to combat flooding: Nigerian, global perspectives’; and the Vanguard titled ‘AI for climate action: Nigerian and global viewpoint’.

My advice to the government would centre on strategic integration, capacity building, and ethical governance. Deploying AI and geospatial analytics can enhance climate resilience, such as employing Sentinel-1 data for oil spill detection. The government should leverage big data to optimise agriculture by predicting crop yields via satellite imagery and improving public health through air quality prediction models to combat pollution. Establishing cloud-based platforms on AWS or Azure will facilitate centralised data access, streamlining information sharing and decision-making.

Furthermore, the government should train policymakers and local agencies in geospatial tools like QGIS and Google Earth Engine, along with data literacy initiatives, which can bridge the technology-knowledge gap. Collaborating with academia and industry experts, as seen in my partnerships with Niger Delta University and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), ensures solutions are grounded in local needs. Supporting open-source initiatives, such as flood mapping projects on GitHub, democratises access to critical tools. Equally important is the ethical and inclusive application of AI. To avoid bias, models must be validated with ground-truth data, as demonstrated in my waste dumpsite studies that combined satellite imagery with soil samples. The government can engage its agencies and local communities in AI projects, such as integrating local flood histories into machine learning training data, ensuring that solutions remain equitable, context-aware, and actionable.

By incorporating these strategies, the government can foster a more resilient, data-driven, and inclusive approach to addressing environmental and societal challenges.

Most people believe that AI is a threat to their jobs. Do you feel that AI is a threat to your job? And, do you think you would be able to catch up with the latest AI trends and innovations as regards your job and career?

AI is not a threat to my job, but a tool that amplifies my ability to solve complex problems. My role as a data scientist and geospatial analyst involves leveraging AI to enhance decision-making, not replace human expertise. For instance, my work on flood prediction models or oil spill detection using Sentinel-1 SAR data relies on AI to process vast datasets, but it requires domain knowledge in geoscience and environmental science to interpret results and design actionable solutions.

To stay ahead, I actively engage with emerging trends through certifications (e.g., AI for Earth Monitoring by EUMETSAT, 2023), open-source contributions (e.g., my flood mapping Jupyter Notebook), and research that integrates cutting-edge techniques like ensemble machine learning and geospatial AI. Continuous learning is embedded in my workflow—whether through cloud platforms (AWS, GCP) or collaboration with cross-disciplinary teams. AI evolves as an extension of my skill set, not a replacement.

What’s the most important skill you teach students to prepare them for geospatial or data science jobs?

Problem-first thinking. I train students to start with real-world issues (e.g.: How do we reduce flood risks?) rather than tools. They learn to select the right techniques (e.g., Python for automation, ArcGIS for mapping) and communicate results effectively to non-technical audiences, mirroring industry demands.

My advice to someone starting a career in geospatial data science is for them to master Python and cloud tools, but also understand domain-specific challenges (e.g., climate science). Contribute to open-source geospatial projects to build a portfolio. Network through conferences like FOSS4G and prioritise ethical AI—solutions must serve people, not just technology.

How do you ensure your projects help local communities?

I collaborate with NGOs and community leaders during project design. For flood mapping, we incorporated local knowledge (historical flood zones) into models. Workshops teach stakeholders to use Tableau dashboards for planning evacuation routes. Solutions are only effective if they align with community needs and capabilities.

What is one big problem you want to solve next using geospatial AI or machine learning?

I aim to build a real-time coastal erosion monitoring system for West Africa. Using the Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, satellite data, and community feedback, the model will predict erosion hotspots and guide adaptive infrastructure planning. This could save livelihoods in vulnerable communities like the Niger Delta.

READ ALSO: Kaduna leads in artificial intelligence — Gov Sani

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Relationship Hangout: Public vs Private Proposals – Which Truly Wins in Love?

- “No” Is a Complete Sentence: Why You Should Stop Feeling Guilty

- Relationship Hangout: Friendship Talk 2025 – How to Be a Good Friend & Big Questions on Friendship

- Police Overpower Armed Robbers in Ibadan After Fierce Struggle