As ‘10 million children risk mental deformity in adulthood’ and 450,000 Nigerian children yearly die due to malnutrition.

In Nigeria, children are faced with one of the unimaginable ways to die – hunger and it doesn’t seem like this problem will go away anytime soon, as the U.N. children’s agency, UNICEF warned earlier in July that an estimated 1.4 million children could die this year from famine-like conditions in Nigeria, South Sudan, Somalia and Yemen.

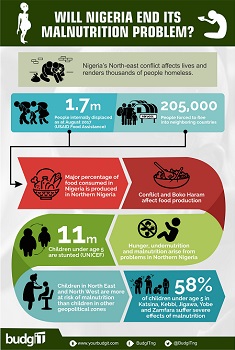

Conflicts, migration, climate change, drought and high food prices have contributed to high levels of food insecurity and chronic malnutrition in the country. As at August 2017, more than 1.7 million people are said to have been internally displaced as a result of armed conflicts in the north-eastern Nigeria, while nearly 205,000 people have been forced to flee into neighbouring Cameroon, Chad and Niger, thus, “straining food resources in the region,” per USAID’s Food Assistance Fact Sheet dated September 21, 2017.

Despite downward trend of Nigeria’s inflation rate, food prices have continued to rise in Nigeria, as shown in the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Consumer Price Index (CPI) report released earlier this month. Although inflation rate dropped year-on-year from 16.01 per cent in August to 15.98 per cent in September (eighth consecutive decline in inflation since January 2017), food inflation rose to 20.32 per cent, from 20.25 per cent in August this year.

As a significant amount of food consumed in Nigeria is produced in the northern Nigeria, conflicts and Boko Haram-related violence and large-scale displacement continue to disrupt food production in the country, “limiting income-generating activities such as agriculture, reducing household purchasing power and access to food,” as the USAID puts it.

“Despite projected average to above-average yields for upcoming harvests in most areas of Nigeria; insecurity continues to limit agricultural production and food availability in the northeast, resulting in the persistent risk of famine levels of acute food insecurity in inaccessible areas. Furthermore, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) projects that emergency levels of acute food insecurity will continue in most of Borno State and in conflict-affected areas of Adamawa and Yobe states until at least January 2018,” the report reads in part.

For more than a decade, hunger, undernutrition and malnutrition have plagued Nigeria, despite several humanitarian efforts from aid workers and agencies in the country, and are likely to continue to ravage the country if the country continues to lack political will to invest in food security and rural development, Dr Adamu Saleh, a food nutritionist in the northern Nigeria says.

Although child nutrition in Nigeria has improved in recent years, as UNICEF puts it, about 11 million children under the age of five are still stunted. With more than half of children under 5 years in northern Nigeria stunted and one in every three, severely stunted social and geographic disparities related to malnutrition in Nigeria are “significant,” as UNICEF puts it.

For instance, “children from the North-West and North-East geopolitical zones are more at risk of malnutrition than children from other geopolitical zones. Underweight prevalence in those two zones is nearly four times higher than in the three southern zones. Results are similar for stunting and wasting prevalence,” the UN children’s agency says.

In five states in the north – Katsina, Kebbi, Jigawa, Yobe, and Zamfara – 58 per cent of under-five children suffer from severe effects of malnutrition, impairing their physical and mental development. In south-west Nigeria, 22 per cent of children under five are severely malnourished, even stunted. Oyo state has 13.2 per cent rate of underweight children, while about 200,000 Osun children stunted due to malnutrition, according to UNICEF. These are the states with highest levels of malnutrition cases in the South-West.

“Nigeria has the highest number of stunted children under age five in sub-Saharan Africa and second highest in the world with 37 per cent of all children stunted, 18 per cent wasting and 29 per cent underweight,” Federal Ministry of Health’s Ogunbumi Omotayo, said late last year.

Stunting, according to United Nations Children’s Fund, is associated with an “underdeveloped brain, with long-lasting harmful consequences, including diminished mental ability and learning capacity and poor school performance in childhood,” among others.

Stunted children who grow into adulthood are at risks of reduced earnings and increased risks of nutrition-related chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, the agency says.

Multiple studies have over the years linked poverty with malnutrition in any given scenario just as available statistics indicate that malnutrition is more prevalent in poor or “developing countries” as against other countries in the world. But more critically is the relationship between lack of information and malnutrition as Dr Omobowale puts it.

At least one in nine people in the world today are hungry; that is, about 800 million people (60 per cent of whom are women) suffer from hunger, per data from Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). An estimated 233 million out of these 800 million people live in sub-Saharan Africa and are undernourished, based on FOA’s 2014-6 most recent estimates. Worldwide, 17.3 million children suffer from severe acute malnutrition.

Last year, about 2.5 million children in Nigeria suffered from severe acute malnutrition, available data showed, with a potential for increase by 2018. Nigeria’s Ministry of Health’s records show that since 2013, Nigeria loses one million children under five-year-olds every year – 45 per cent (450,000) of those deaths are due to causes attributed to malnutrition. The ministry also put malnutrition related maternal mortality at 2,300 daily, making the country the “second largest contributor to the under-five and maternal mortality rate in the world,” and one of the six countries that account for half of all child deaths from malnutrition worldwide, the UNICEF says.

Despite the connection between poverty and malnutrition, Dr Omobowale says he sees “ignorance as the leading cause of malnutrition in Nigeria” and he’s “more concerned about the power of knowledge in all this because even for the poor, if they’re appropriately educated, then malnutrition should be at the barest minimum.”

According to him, beyond poverty, I see ignorance plays a critical role in permeating malnutrition in the country “and there is also a relationship between poverty and ignorance. Because a lot of the time, the information that you are able to pay for maybe more convincing than what travels around and that is why ailments such as malnutrition are more associated with the lower classes.”

He said this lack of information influences adults choices in selecting what food to feed their children with, based on the assumption that procuring healthy meals might be too expensive for them to afford.

“Number one, the lower classes, due to perhaps to the level of their finances, assume that ‘oh, I cannot afford this or this kind of meal would be too expensive to be given to this child, we better spend that money on other things.’” This ignorance, he says, is dangerous because, in most cases, those healthy foods are within their environments and are not expensive at all. This ignorance, he says, help pervade malnutrition, leaving severe impacts on Nigerian children’s health.

Malnutrition’s lifelong impacts on children’s health – “13 per cent of Nigeria’s children may grow to become mentally deformed in adulthood”

Malnutrition can cause life-threatening problems for children and can leave them with lifelong consequences such as acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea episodes, hypertension and type II diabetes, according to Dr Michael Olugbile, a Harvard trained public health expert.

Emeritus professor of nutrition and former President of the Nutrition Society of Nigeria, Professor Babatunde Oguntona, at a Nutrition Symposium on “Malnutrition, Child Development and the Media” in August this year, said 10 million Nigerian children, that is, 13 per cent of Nigeria’s children may grow to become mentally deformed in adulthood, due to nutrient deprivation, particular lack of iodine in the diet.

“First we have a lot of children in this country who have escaped childhood period and carried over a lot of nutrient deficiency into their early school years. But they are able to continue and the longer they live, the more nutritional deficiency takes effect,” he said at the time.

Malnutrition and children’s education potential

Because malnutrition can impede cognitive development and limit learning capacity, nutritionists and educationists say malnutrition can lead to an overall low academic development among children. Already, more than 10 million Nigerian children are out of school and 37 per cent of all Nigerian children are affected by effects of malnutrition. “This is alarming for our country,” Dr Olumuyiwa Omobowale, development sociologist in the University of Ibadan said.

Lower school attendance has been linked to “decreased the accumulation of human capital during childhood and adolescence,” according to UNICEF, which said stunting in early life is linked to 0.7-grade loss in schooling, a seven-month delay in starting school and between 22 and 45 per cent reduction in lifetime earnings.

Investing in nutrition, a possible solution

The European Union once asked governments to make the fight against malnutrition a political and financial priority by developing policy and mobilising resources needed to scale up the implementation of nutrition interventions in their countries. In January this year, Nigeria commenced the National Home Grown School Feeding Programme (NHGSF) country in three pilot states (Osun, Anambra and Kaduna) and is expected to cover no fewer than 10 million primary school pupils from classes 1-3. The programme has the potential to cover another five million pupils in primaries 4-6 by state governments through a counterpart funding arrangement, according to Nigeria’s federal government.

The school feeding programme has been hailed as encouraging increased enrolments in schools in states where it is operational, especially as Kaduna State says it witnessed an increase of 400,000 pupils just after one session of operating the school feeding programme. Despite this, however, there has been called for more investments in food security and rural development.

Grace Adebayo, a women and children empowerment advocate working in Mali, said the need for African governments to invest in children and maternal nutrition is urgent, saying that the investment, which the World Bank puts at $188 million a year, could help prevent reduced productivity, which in turn could improve healthy workforce and by extension, improve the national economy.

Why investing in nutrition and rural development is key

Available data from multiple United Nation agencies shows that mortality and morbidity associated with malnutrition represent a direct loss of human capital and productivity for the economy. However, World Bank estimates show that annual investments of $347 million to provide micronutrients to 80 per cent of the world that are malnourished would yield $5 billion in improved earnings and healthcare spending. It is calculated that each dollar spent on nutrition delivers between $8 and $138 of benefits, thus, “improving nutrition contributes to productivity, economic development, and poverty reduction by improving physical work capacity, cognitive development.”

Basically, economic returns to investing in nutrition are very high.