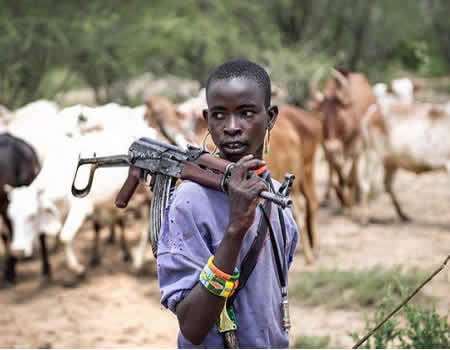

Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, Professor Wole Soyinka, once argued that “herdsmen, let us appreciate, are perhaps humanity’s earliest known tourists. They must be taught however that there is a culture of the settlement, and learn to seek accommodation with settled hosts wherever encountered.” This strand of thought holds true as found in many parts of Africa. For many herders like Haruna Ali, mobility has been one constant aspect of their life. There was a saddening despondency in his gaze. It was long, frail. His words were few and far-between, revealing a depressing nostalgia. He had a most memorable childhood. He was raised in Kwambai, Taraba State. He knew no other life than that of a herdsman. He intoned that, as a boy, he would move the cattle to graze from a “mere shouting distance” from his village.

But his narrative took an aching trajectory when he lamented that the grazing lands were no longer there, only long stretches of grassless plains, imposed by a rapidly growing desertification. With no pasture, Haruna resorts to grazing even outside the immediate boundaries of Nigeria.

“We know no other life than the life that we share with our animals; when they are fat, our joy knows no bound. Again, when they are ill, we have no reason to be happy. When I was a boy, the grass that surrounds our village used to be tall as human beings. There was enough and even surplus for our cattle. But it is no longer the same—no grass, no water. We lose our cattle to hunger and thirst,” he said, dispelling a hurting sigh.

Haruna’s dismal narrative is not a personal tragedy as it is shared by a huge chunk of cattle rearers who had plied their craft through the years in the northern part of Nigeria. This unnerving challenge is due to the growing advancement of the desert into areas and plains that had one time or the other being fertile for grazing cattle and farming.

Speaking further, he said: “We travelled through many tracks. The tracks were introduced to us by our parents. We followed them as they travelled from this part of the country to the other. Unfortunately, today, we cannot find those tracks anymore. This is a serious problem for many of us. As we move from one spot to the other, we are faced with obstacles in our routes. Such routes once served as areas where we fed our cattle.”

As touching as Haruna’s plight appears, more disturbing is the present spate of violence across Nigeria with the rising cases of repeated clashes between farmers and herdsmen.

The problem

In Nigeria, grazing routes established many decades back have become points of conflicts between herdsmen and farmers. From the North to sections of the Middle Belt to parts of the South, there have been rising disagreements as the herders have argued that the grazing corridors have been converted to other uses.

Nigeria’s population has grown from 33 million in 1950 to about 192.3 million today. This phenomenal increase of the population has put enormous pressure on land and water resources used by farmers and pastoralists. One of the outcomes of this process has been the blockage of transhumance routes and loss of grazing land to agricultural expansion and the increased southward movement of pastoralists has led to increased conflict with local communities. This is particularly the case in the Middle Belt – notably in Plateau, Kaduna, Niger, Nassarawa, Benue, Taraba, and the Adamawa States. The conflicts primarily involve Fulani pastoralists and local farming communities.

As violence between herdsmen and farmers has grown and developed into criminality and rural banditry, popular narratives in the form of hate speech have exacerbated the crisis.

It is clear that Nigeria, and indeed Africa, have to plan towards the transformation of pastoralism into settled forms of animal husbandry. The establishment of grazing reserves provides the opportunity for practising a more limited form of pastoralism and is, therefore, a pathway towards a more settled form of animal husbandry. Nigeria has a total of 417 grazing reserves out of which only about 113 have been gazetted. It is clear that at least in the short and medium term, many herds must continue to practise seasonal migration between dry and wet season grazing areas. Ultimately, there is the need for permanent settlement of pastoralists.

Stakeholders under the Nigerian Working Group on Peace Building and Governance, have proposed a number of interventions to resolve the herdsmen/farmers clashes across the country.

The peace committee members, including, Professor Ibrahim Gambari, former Chief of Army Staff, General Martin Luther Agwai (Rtd), Human Rights activist, Professor Jibrin Ibrahim, former Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Professor Attahiru Jega, Dr. Chris Kwaja, Ambassador Fatima Balla, Dr. Nguyan Fesse, Mrs Aisha Muhammed – Oyebode and Mallam Y.Z. Ya’u, in a memo submitted to President Muhammadu Buhari, delved into the genesis of the crisis and identified some key possible solutions.

The memo titled “Pastoralist-Farmers Conflicts and the Search for Peaceful Resolution,” according to Professor Jibril Ibrahim, was aimed at finding a holistic solution to the challenge which the group attributed to a variety of factors.

The group attributed the incessant problems to growth in population, failure of the Old Northern Region to gazette the demarcated grazing reserves, failure of laws and politicisation of issues, noting that a holistic approach which would include a grand meeting of all stakeholders should solve the problem.

The executive summary of the memo reads: «Pastoralist-farmers’ conflicts in Nigeria have grown, spread and intensified over the past decade and today poses a threat to national survival. Thousands of people have been killed, communities have been destroyed and so many farmers and pastoralists have lost their lives and property in an orgy of killings and destruction that is not only destroying livelihoods but also affecting national cohesion. Nigeria has about 19 million cattle, much of it in the hands of pastoralists, and we need to seek solutions to the problem of pastoralism while resolving the problem of insecurity that has arisen.

One of the greatest difficulties in addressing and resolving issues surrounding pastoralism is the politicisation of legal regimes and the blockages to the enactment of or implementation of laws that can redress the key challenges posed. In 2016 for example, a bill was proposed – ‘‘A Bill for an Act to Establish Grazing Reserve in each of the states of the federation to improve agriculture yield from livestock farming and curb incessant conflicts between cattle farmers and crop farmers in Nigeria’’ was thrown out. There is an emerging conflict between the constitutional principle on free movement of persons and goods and laws emerging in some states restricting movement. Some states have enacted laws or are processing bills to prevent open grazing on their territory. There are four initiatives so far in Benue, Ekiti, Taraba and Edo states. Could such laws be effective in prohibiting pastoralism, which is practised by millions of Nigerians?

Developing a comprehensive policy framework

A new policy framework on the farmers-pastoralists crisis should be developed that is both comprehensive and mutually beneficial to both groups. An inter-ministerial committee should be constituted with experts and stakeholder membership to draw up the framework. There must be a consultative process that listens to the concerns of all stakeholders in developing the new framework so that the outcome would have national ownership. Pastoralism is not sustainable in Nigeria over the long term due to high population growth rate, expansion of farming and loss of pasture and cattle routes. At the same time, pastoralism cannot end or be prohibited in the short term, as there are strong cultural and political economy reasons for its existence. The new policy should develop a plan for a transitional period during which new systems would be put in place. The framework should map out the duration, strategy and timelines for the transition plan. Finally, a comprehensive approach to address the growing crisis associated with violence affecting pastoralism and farmers in Nigeria should be addressed.”

The cattle colony concept

Media assistant to the Minister of Agriculture, Audu Ogbeh, Dr Oyeleye Olukayode, notes that the cattle colony is fashioned after the Farm Settlement Scheme and was designed primarily to create an enclave where all requisite infrastructure and services are made available for smooth cattle husbandry and allied businesses.

According to him, “unhindered evolvement of cooperative groups, products prices control and facilitated cluster and off-takers mechanism is the strongest attractions of the concept. The Karachi/Pakistani Cattle and buffalo colony is an enduring example; it is reputed to have emerged around 1935 and officially recognised since 1963. The proposed cattle colonies are targeted at addressing the contemporary issues of pastoralism and transhumance in Nigeria. It is conceived to be a multistakeholder process with strong incentives to encourage grassroots’ ownership and efficient liaison and constructive engagement mechanism.

“Although the enclave designated for series of livestock holdings is called a livestock colony, the tendency everywhere colonies have been established is the emergence and extension of holdings beyond the original and documented boundaries. Towards addressing the critical issues of Nigeria’s pastoralism and herd’s management, the Federal Government, through the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is setting up 5000Ha cattle colonies in at least 21 states of the federation equipped with all requisite infrastructure and facilities.”

Commissioner for Information, Culture and Tourism in Nasarawa State, Honourable Abdulramid Kwarra, has attributed the current crises between herdsmen and farmers to the overtaking of grazing routes by development and population growth.

Nigerian Tribune gathered that some strategic parts of Lafia, which include the land where the present day Precious FM Lafia occupies, the land occupied by the present Nasarawa State House of Assembly, and present cattle market in Lafia, were all grazing routes in the state.

Kwarra, who disclosed this during an interview with Nigerian Tribune in Lafia, the capital of the state, said there have been clearly demarcated routes in Northern Nigeria during in the sixties.

“In the sixties, the population of Nigeria was 60 million, but today we have 180 million Nigerians, therefore the population of the country has grown and this has led to the taking over of most of these grazing routes, leaving the Fulani herdsmen to look for alternative grazing routes,” he said, noting that unfortunately this alternative grazing routes sometimes encroach into some farmlands which result in dispute.

He stated that in the past, there were the laws of Northern Nigeria which were put in place by the then regional government to regulate grazing, which included grazing routes, and dispute resolution. Kwarra proffered that, the issue should be holistically looked into and resolutions should be made to create cattle colonies or return the old grazing routes.

The situation in Plateau State

Plateau State Chairman, Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association, Mallam Mohammadu Nura, affirmed the route plans establish in earlier times, noting that part of the routes that had since been taken over by development in Plateau State, include Bauchi-Toro, Mista Ali, Dass-Mai Juju-Riyom, Foron-Angwaren-Wareng-Hawan Kibo, Foron-Kassa-Jol-Bachit-Wamba in Nasarawa State.

According to him, the routes over the years suffered deliberate encroachment by farmers and others who didn’t believe in the existence of Fulani herdsmen or who perceived the occupation as a threat to their means of livelihood.

National Secretary of Gan Allah Fulani Development Association of Nigeria (GAFDAN), Alhaji Sale Bayari, said most of the international and local routes had since fizzled out of existence. He added that the international routes in Maiduguri, Yobe, Katsina, Taraba, among others, were no longer in place.

Bayari said the grazing reserves and cattle routes established in the 60s were backed by Nigerian law and Northern Nigeria Law, and that in the 70s to the late 80s, the federal ministry of agriculture and forestry was saddled with the responsibility of managing the routes, “but all these routes are no longer operational in the country. They were deliberately wiped out by farmers to make thing difficult for the herdsmen. In some instances, the farmers placed poisonous crops on cattle routes. Go round Plateau and other states in the country today, people have deliberately taken over these routes by farming on them, erecting structures and many other things to frustrate movement of cattle.”

All efforts to speak with government officials from the state ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Justice proved abortive as many of them declined to comment and considered the issue controversial.

However, a top government official, who spoke with Nigerian Tribune on the condition of anonymity said cattle routes linking up grazing reserves throughout the country with no provision for security, is an open invitation for foreign invaders to infiltrate and traverse the length and breadth of the country at will, adding that the routes, if allowed in this dispensation, might be safe corridors for the transportation of contraband goods or weapons.

“If our past experience is anything to go by, we have not been able to police are few pipelines in the South-South and South-West of the country, can we dream of putting adequate surveillance in place for all grazing reserves and stock routes throughout the country? Even without a grazing reserve law in place, the nomads refused to allow the JTF personnel access into their enclaves in Baraking Ladi and Riyom Local Governments of Plateau State in 2012, following the deaths of Senator Gyang Dantong and Hon. Gyang Fulani.

“However, most of the routes in Plateau State are no longer in existence while attempt to recreate them might spark up a fresh row between the farmers and the herdsmen,” the official stated.

Ibrahim Abdullahi, Assistant Secretary General of the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association, shared insight into the grazing routes, the laws, as well as recommendations for addressing the problems associated with grazing.

Speaking of the function of touted for herdsmen, Abdullahi said: “These routes are routes used by the herdsmen to migrate from one locality to the other. They are also known as the stock routes. They were demarcated and documented, but unfortunately neglected by the government such that these routes have encroached beyond redemption. Today, only a few exist. Usually, for those using the routes, if they got to where they have encroached they divert and link up before they reached their destination. There are routes like any other states in the country and these routes are divided into three. There is the international route, inter-states routes, as well as inter-local government routes. It may interest you to know that these routes have been there even before the coming of colonialists. And when they came, they made use of these stock routes to construct most of the trunk A roads we have in the country, especially in the northern states.”

On laws, he noted that “There are national and international laws backing these laws. In Northern Nigeria for example, there are laws prohibiting any human activity 10 km radius within any route. But these laws were neglected and dumped because the government have lost interest in these routes or livestock sector.”

He also stated that “Government attention over the years has shifted to arable agriculture, with the increase in population This prompted the need for more farmlands and this invariably affected the grazing routes. You have to understand that the land does not increase an inch, but it is the human population that increases every day. So, government’s nonchalant attitude to livestock became very clear. For instance, if you go to any Ministry of Agriculture in any state, you will find out that less than 2 percent is usually being budgeted for livestock. So, this scenario became the order of the day and, over time, affected the economy of the Fulani herdsmen to the extent that today some of them resort to all sorts of crime. So, this neglect has been going on for over 38 years, while at the other hand, the outbreak of the Rinderpest disease in 1983, which led to the death of over 60 million cows in the North, grossly affected the fortunes of the herdsmen. Unfortunately, the government didn’t take any action, forgetting that a typical Fulani man only knows how to rear his cattle but he does not own a shop, nor does he have a farm, or have formal education.”

For solutions to the clashes, he said: “Only government can redeem the situation, because the reality on the ground is you cannot force Fulani to leave because they have equally increased in population and they have equal rights like any other Nigerian to live where ever they like. But the government should first of all gazette all the grazing reserves so that the indigenous Fulani can remain in one place, and amenities like school and health can be established for them to create a sustainable future for the future generation. The era of 1965 or 1975 where a Fulani can move with his cattle from Kano to Enugu without interruption or encroachment on anybody’s land has gone. So, the government should take the bull by the horn and gazette its grazing reserves so that the indigenous Fulani will be settled in one place, then the government should look at the possibility of resting entry of foreign pastoralists because we don’t have enough routes to accommodate them. That will also mean the government should review its region engagements with ECOWAS and AU which allow a Fulani from the Gambia to enter the country without restrictions. If the farmers support this move, they will be the greatest beneficiaries, because no herdsmen will encroach on their farmlands.”

Govt should fight desertification in North —IEDPU

National president of the Ilorin Emirate Descendants Progressive Union (IEDPU), Ambassador Uthman Abdulazeez, who is a career diplomat with a background in geography, called on the Federal Government to do the needful to address the rampaging herdsmen/farmers clashes in some parts of the country.

Abdulazeez, who said the crisis would continue as long as the Federal Government failed to encourage green belt zone as recommended by the World Bank, added that government should discourage desertification in the northern parts of the country.

“That’s part of the needful I said that the government should urgently look into to address the situation. I have a background in geography and that’s why I can trace the issue to the cattle route. In the Ilorin metropolis, there is an area called Opo Malu, otherwise called cattle route. That’s how it is most parts of the country, from south to North. There were grazing reserves across Kwara State.

“However, population explosion and urbanisation, has brought about the current situation. If not for the mechanism put in place by the Emir of Ilorin that has checkmated such clashes in the area, we would have had such occurrences too. The emir is always in constant touch with the grassroots, promoting peaceful and harmonious coexistence.

“The issue of herdsmen attacks cannot also be divorced from the issue of climate changes. This has made the Sahara desert expand. The cattle breeders need grass to feed their cattle, but the grassland is decreasing. We were warned by the World Bank experts on the imminent challenges of climate change,” he stated.

WATCH TOP VIDEOS FROM NIGERIAN TRIBUNE TV

- Let’s Talk About SELF-AWARENESS

- Is Your Confidence Mistaken for Pride? Let’s talk about it

- Is Etiquette About Perfection…Or Just Not Being Rude?

- Top Psychologist Reveal 3 Signs You’re Struggling With Imposter Syndrome

- Do You Pick Up Work-Related Calls at Midnight or Never? Let’s Talk About Boundaries